Who Throws Whom Overboard?

Oliver Ressler

Salt Galata

November 23, 2016 – January 15, 2017

![8 The Economy Is Wounded Oliver Ressler, <i>The economy is wounded - let it die!</i> [Ekonomi yaralı - bırakın ölsün!], 2016](/directus/media/thumbnails/8_the_economy_is_wounded-1-jpg-780-5000-false.jpg)

Oliver Ressler, The economy is wounded - let it die!, 2016

Who Throws Whom Overboard? is a major exhibition of Oliver Ressler’s works dating from 2004-2016, and his first in Istanbul since the presentation An Ideal Society Creates Itself at Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center in 2005. The exhibition brings together photographic works, wall texts, films and installations addressing migration, borders, citizenship, capital and alternative economics. It does not suggest that these “issues” are related in terms of policy, but rather that they can be read as the conjoined faces of an ongoing, global crisis.

Ressler’s works make present the disembodied voices and visible archives of crisis and its nemesis. He describes the nemesis as “the social invention directed against the status quo with which the stateless and propertyless confound competitiveness, bury barbed-wire checkpoints or turn factories inside-out. This is the least that’s required if planetary survival and a form-of-life worth living are ever to be salvaged from the shipwreck known as The Economy.”

In the gallery on floor -1, the exhibition is composed around a newly commissioned film that was produced by Ressler in Istanbul during the summer of 2016. After a period of research around self-organized activities in the city and the local refugee situation Ressler focused his attention on Syrian individuals who have declined to beg for “asylum” from institutional Europe, choosing instead to continue their lives in Istanbul. In the film There are no Syrian refugees in Turkey (2016) recorded conversations with Syrian refugees describe a “guest” life in the continent’s largest metropolis. The orators talk about the difficulty of making a living here, and the reluctance of the EU to admit more than a pitiful number of refugees. The conversations were recorded in Arabic in the weeks following the 15th July coup attempt in Turkey; in the midst of a crisis that threatened Turkey’s stability and governance, the refugees felt the fragility of their own situation acutely. Quietly reversing the whole perspective of the Western “refugee debate,” the film develops a political analysis of Turkish and European politics from the standpoint of the Syrian refugees.

Appearing alongside There are no Syrian refugees in Turkey is Ressler’s previous film, Emergency Turned Upside-Down (2016). Here the artist confronts the cynical and inhuman discourse that calls the presence of refugees in Europe an “emergency”: a word better suited to descriptions of war, terror and economic strangulation that force people to move. The film counterposes the vast imaginative potential of a borderless world to the petty prison of nationality and the external, internal and social borders it imposes. The narrating voice is shadowed by drawn animations in black and white. Overlapping lines form an abstract pattern, evoking – among other things – borderlines, migration routes, outlines of states, life-lines and human heart rates.

While Turkey has opened its borders to nearly three million refugees – more than the number accepted by all European states combined – the EU border regime is responsible for the drowning of tens of thousands in the Mediterranean Sea. A large-format photograph in the exhibition space alludes to this new genre of images of dead bodies on beaches, yet the men in the photographic series Stranded (2015) wear business suits, the standardized clothing of politicians and managers. Stranded imagines what might happen if the managers of today’s economy – those for whom there is no alternative to corporate profit and human loss – were themselves sacked and thrown overboard. Other works from the same series are displayed throughout the SALT Galata.

Stranded is directly linked to another large-format digital print, The economy is wounded – let it die! (2016), in which a sea crowded with sinking container ships and other vessels evokes an economic system that depends on global trade, a daily cause of ecological and social disasters. This work joins the critical debate that starts with the recognition that nothing but systemic economic transformation – including radical curtailment of worldwide trade and shipping – can counteract climate change and associated global threats.

The 3-channel video installation Occupy, Resist, Produce (2014/2015; with Dario Azzellini) explores economic models that seem more viable for the future. It shows three factories in Milan, Rome and Thessaloniki where the purpose of factory occupations was to bring production under workers’ control. The workers take the initiative and become protagonists, creating horizontal social relations on the production sites and adopting mechanisms of direct democracy and collective decision-making. The recuperated workplaces often reinvent themselves, building links with local communities and social movements.

On the first floor of the building is the film The Right of Passage (2013; with Zanny Begg). It focuses on struggles to obtain citizenship, while also questioning the inherently exclusive nature of citizenship. Interviews with Sandro Mezzadra, Antonio Negri and Ariella Azoulay open a discussion with a group of people living “without papers” in Barcelona.

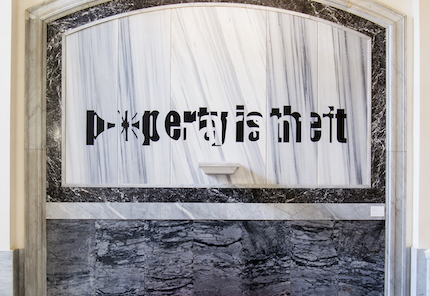

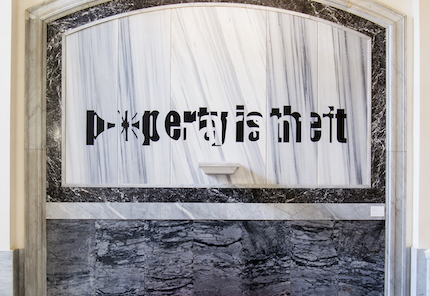

Additional works are presented throughout the building, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s anarchist slogan Property is Theft (2014/16), which has been applied to the marble entrance-wall; a poster on institutional racism (2004; with Martin Krenn); and the floor pieces Emergency Turned Upside-Down (2016) featuring the overlapping (and newly arranged) borderlines of the states from the so-called Balkan route which was a central migration route used by refugees from Syria and the wider war-zone in their attempt to reach the EU.

During the opening weeks of the exhibition the work Too big to fail (2011) is presented in two city locations on advertising billboards. Too big to fail is how politicians assess major banks during economic crises and why they claim that banks should be bailed out through public money. Banks are regarded as essential to the system; their poor performance can endanger the entire capitalist system. Presented outside of SALT, and hence outside the physical architecture owned by Garanti Bank, Too big to fail proposes an image of the desire that the global movement for a democratic transformation becomes system-relevant, no longer ignored by those in power.

Thanks to Matthew Hyland for the exhibition title idea.

Oliver Ressler lives and works in Vienna and produces works on issues such as economics, democracy, global warming, forms of resistance and social alternatives. He has shown extensively internationally and a retrospective of his films took place at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in 2013. He is the co-curator of an exhibition cycle on the financial crisis, It’s the Political Economy, Stupid, and co-curator of Utopian Pulse – Flares in the Darkroom at Secession, Vienna, 2014. Ressler is the first prize winner of the newly established Prix Thun for Art and Ethics Award, 2016.

Ressler’s works make present the disembodied voices and visible archives of crisis and its nemesis. He describes the nemesis as “the social invention directed against the status quo with which the stateless and propertyless confound competitiveness, bury barbed-wire checkpoints or turn factories inside-out. This is the least that’s required if planetary survival and a form-of-life worth living are ever to be salvaged from the shipwreck known as The Economy.”

In the gallery on floor -1, the exhibition is composed around a newly commissioned film that was produced by Ressler in Istanbul during the summer of 2016. After a period of research around self-organized activities in the city and the local refugee situation Ressler focused his attention on Syrian individuals who have declined to beg for “asylum” from institutional Europe, choosing instead to continue their lives in Istanbul. In the film There are no Syrian refugees in Turkey (2016) recorded conversations with Syrian refugees describe a “guest” life in the continent’s largest metropolis. The orators talk about the difficulty of making a living here, and the reluctance of the EU to admit more than a pitiful number of refugees. The conversations were recorded in Arabic in the weeks following the 15th July coup attempt in Turkey; in the midst of a crisis that threatened Turkey’s stability and governance, the refugees felt the fragility of their own situation acutely. Quietly reversing the whole perspective of the Western “refugee debate,” the film develops a political analysis of Turkish and European politics from the standpoint of the Syrian refugees.

Appearing alongside There are no Syrian refugees in Turkey is Ressler’s previous film, Emergency Turned Upside-Down (2016). Here the artist confronts the cynical and inhuman discourse that calls the presence of refugees in Europe an “emergency”: a word better suited to descriptions of war, terror and economic strangulation that force people to move. The film counterposes the vast imaginative potential of a borderless world to the petty prison of nationality and the external, internal and social borders it imposes. The narrating voice is shadowed by drawn animations in black and white. Overlapping lines form an abstract pattern, evoking – among other things – borderlines, migration routes, outlines of states, life-lines and human heart rates.

While Turkey has opened its borders to nearly three million refugees – more than the number accepted by all European states combined – the EU border regime is responsible for the drowning of tens of thousands in the Mediterranean Sea. A large-format photograph in the exhibition space alludes to this new genre of images of dead bodies on beaches, yet the men in the photographic series Stranded (2015) wear business suits, the standardized clothing of politicians and managers. Stranded imagines what might happen if the managers of today’s economy – those for whom there is no alternative to corporate profit and human loss – were themselves sacked and thrown overboard. Other works from the same series are displayed throughout the SALT Galata.

Stranded is directly linked to another large-format digital print, The economy is wounded – let it die! (2016), in which a sea crowded with sinking container ships and other vessels evokes an economic system that depends on global trade, a daily cause of ecological and social disasters. This work joins the critical debate that starts with the recognition that nothing but systemic economic transformation – including radical curtailment of worldwide trade and shipping – can counteract climate change and associated global threats.

The 3-channel video installation Occupy, Resist, Produce (2014/2015; with Dario Azzellini) explores economic models that seem more viable for the future. It shows three factories in Milan, Rome and Thessaloniki where the purpose of factory occupations was to bring production under workers’ control. The workers take the initiative and become protagonists, creating horizontal social relations on the production sites and adopting mechanisms of direct democracy and collective decision-making. The recuperated workplaces often reinvent themselves, building links with local communities and social movements.

On the first floor of the building is the film The Right of Passage (2013; with Zanny Begg). It focuses on struggles to obtain citizenship, while also questioning the inherently exclusive nature of citizenship. Interviews with Sandro Mezzadra, Antonio Negri and Ariella Azoulay open a discussion with a group of people living “without papers” in Barcelona.

Additional works are presented throughout the building, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s anarchist slogan Property is Theft (2014/16), which has been applied to the marble entrance-wall; a poster on institutional racism (2004; with Martin Krenn); and the floor pieces Emergency Turned Upside-Down (2016) featuring the overlapping (and newly arranged) borderlines of the states from the so-called Balkan route which was a central migration route used by refugees from Syria and the wider war-zone in their attempt to reach the EU.

During the opening weeks of the exhibition the work Too big to fail (2011) is presented in two city locations on advertising billboards. Too big to fail is how politicians assess major banks during economic crises and why they claim that banks should be bailed out through public money. Banks are regarded as essential to the system; their poor performance can endanger the entire capitalist system. Presented outside of SALT, and hence outside the physical architecture owned by Garanti Bank, Too big to fail proposes an image of the desire that the global movement for a democratic transformation becomes system-relevant, no longer ignored by those in power.

Thanks to Matthew Hyland for the exhibition title idea.

Oliver Ressler lives and works in Vienna and produces works on issues such as economics, democracy, global warming, forms of resistance and social alternatives. He has shown extensively internationally and a retrospective of his films took place at Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in 2013. He is the co-curator of an exhibition cycle on the financial crisis, It’s the Political Economy, Stupid, and co-curator of Utopian Pulse – Flares in the Darkroom at Secession, Vienna, 2014. Ressler is the first prize winner of the newly established Prix Thun for Art and Ethics Award, 2016.