Gülsün Karamustafa : A Vagabond, From Personal To Social, From Local To Global

SOLMAZ BULUNDAY HASGÜLER AND TUNA ŞARE

October 31, 2014

Fig. 1. Gülsün Karamustafa, Mystic Transport (1992), mixed media, 20 pieces, each 23 5/8" x 17 ¾" x 35 ½". Third International Istanbul Biennial, Feshane, Istanbul.

The art of Gülsün Karamustafa (b. 1946) ranges from painting to multimedia installations to photography and video. Although her starting point may be local issues and her personal history, her works refer to larger concerns of the modern world. She told an interviewer, “My relation with art did not develop from personal satisfaction or from the need to glorify what I do. I have been carrying art as a heavy mission from the very beginning. I always have the thought that I need to produce and carry this production to a significant place.”1 These words underline that her works have social and political references and that change is a constant force.

Born in Turkey to a middle-class family, Karamustafa’s father was a prominent radio host. She spent her early childhood in Ankara, where she received her early education in painting. Later, with the support of her family she studied painting at Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts, graduating in 1969. As a painter, art director, and contemporary artist, she has witnessed the political events and economic upheavals that have done and continue to shape modern Turkey. Internal migration waves, especially from rural Central and Eastern Anatolia to urban cities like Istanbul and Ankara, started in Turkey in the 1950s. The military coups of 1971 and 1980, and their reforms were significant breaking points in Turkey.2 After 1980, the application of neo-liberal policies and the intensity of militarist discourse affected artists, including Karamustafa, who tried to overcome feelings of being caught up in these issues by “taking refuge in production.”3 The following decade, after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, was marked by an external wave of migration to Turkey from economically challenged Eastern Bloc countries and Russia. It can be said that Karamustafa’s forty-year art career was formed by coups and socio-political changes in Turkey and their intersections with her personal history.

Thematically, Karamustafa’s works fall into three main categories. First are her works that deal with the concepts of migration, identity, hybridism, memory, and boundaries. In the second category are works that explore her personal history and her own experiences as they relate to those themes in the first category. Finally, there are works about gender roles and femininity. Her works also can be classified based on their different materials, techniques, and methods. She uses many mediums in her works and installations, including canvas, ready-made objects, photographs, and video. Her first major experience in film, as the art director of the film “Bir Yudum Sevgi” (A Sip of Love) (1984), directed by the prominent Turkish film director Atıf Yılmaz,4 greatly influenced her future work. Although her later video projects may have different themes, they carry the traces of such earlier experiences with cinema.

The ambiguity of boundaries through the concept of migration and hybrid situations formed as a result of migration is one of Karamustafa’s frequent themes. She has discussed different kinds of boundaries—cultural, sexual, and territorial—and through her work has tried to show the hybridities within these boundaries.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the artist questioned and interpreted social and cultural events first in paintings and later in tapestries. She combined sacred images belonging to different cultures and time frames, and used Istanbul as a bridge for uniting West and East. She incorporated items of kitsch in her works to reflect the cultural corruption that occurred as a result of internal migrations in the 1970s and 1980s, especially from rural eastern Turkey to the western cities. By 1985, these kitsch images had become three-dimensional objects aimed at revealing information about Turkey as a new Arab-influenced lifestyle was becoming increasingly popular and a hybrid culture was being formed by people that had migrated to the cities.

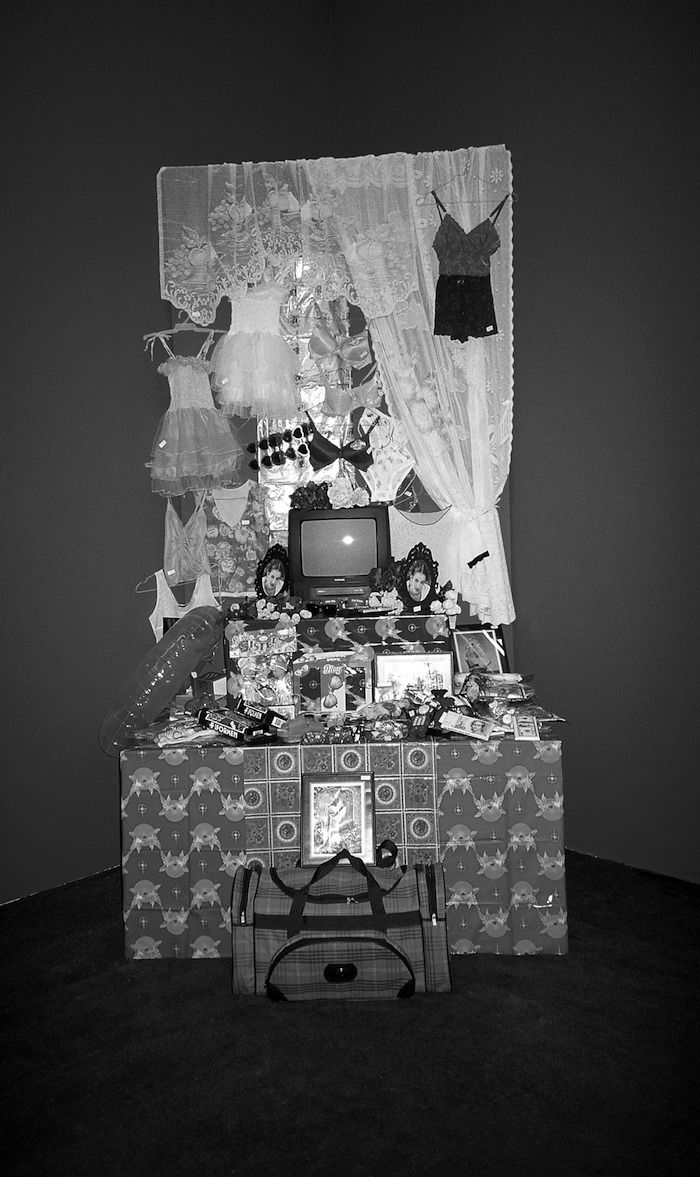

Although Karamustafa included kitsch objects as they are in everyday life, she distanced herself from these materials to evoke various interpretations. For example, in Mystic Transport (1992; PI. 7 & Fig. 1),5 colorful blankets in large baskets typically used for moving made reference to the lives of people who had to migrate but belonged nowhere. The migration theme reoccurs in several works that were exhibited in international shows. Heitmat Ist wo Mann Isst (Homeland is not where you are born, but the place that feeds you) (1994)6 consisted of three pieces of spoons wrapped in gauze and under which was written “Heimat Ist wo Mann Isst.” For her video Stairway (2001; Fig. 2), she recorded the work conditions of a group of gypsy children who had migrated from Eastern Europe. The “stairway” of the video was built in the 1850s by Abraham Salomon Kamondo, an important Jewish broker of Istanbul’s Karaköy district. The children made music and collected money at this spot. They had come with their families for three months (the length of their visas) to Istanbul, where they lived in poor conditions and earned money before having to return to their home countries.

Related to the concept of migration is hybridization, and among Karamustafa’s works on this theme is Genealogy (1994; Pl. 8). While searching for the identity of Zeynep Sultan, an Ottoman princess, for a movie project for the Turkish Radioand Television Corporation (TRT), she found the Sultan family tree, which inspired this work. She listed the royal women’s birth names and their Ottoman names, given to them when they became members of the Ottoman harem; she showed that Byzantine names such as Asporça, Efrandize and Halifira were replaced in time by Islamic names such as Hüsnümelek, Nevfidan, and Hayrandil. She placed ribbons on a small piece of acetate, referring to these women by name. Karamustafa tried to present the place of women in Ottoman culture through a sociological approach. There was tension over the differences in names between Ottoman emperors’ wives, whose names had meanings about their beauty, and their daughters, whose names were mostly taken from Koran. The artist said that her work was “based on the observation of legitimacy.”7

For another work about cultural hybridization, Postposition (1995; Fig. 3),8 five framed tapestries were presented as Byzantine icons.9 Although displayed as carpet-like objects typical of a predominantly Muslim society, these tapestries incorporated religious and cultural motifs belonging to Christianity and Western society, such as the images of Christ as a shepherd and Elvis Presley.

The relationship between the center, the periphery, and postcolonial approaches in art was the theme of Presentation of an Early Representation (1996) and Trellis of My Mind (1998).10 Trellis of My Mind presented overlapping Jewish, Christian, and Islamic images and writings as if they represented a single religion. Other artists in this exhibition included Ghada Amer, Mona Hatoum, and Shirin Neshat, all of whom have become well known in the West. Presentation of an Early Representation was based on a sixteenth-century watercolor by an anonymous German painter that, despite its early date, resembled the orientalist paintings of the nineteenth century. In Karamustafa’s painting, European women, including a black woman, appear as if they are in a slave market, where eastern men are choosing women by touching their breasts or putting their hands under the women’s skirts. Her painting carries almost all of the elements of an orientalist painting, but by basing her work on a sixteenth-century work that represents a much earlier western outlook towards the East, Karamustafa is questioning the eastern identity as presented by a westerner.

A later work, Fragmenting/Fragments (1999; Pl. 9),11 is about the deconstruction of this orientalist view. Karamustafa reproduced female figures from nineteenth-century orientalist paintings and then cut them into pieces and recombined the fragments. She combined feet, breasts, hands, and pieces of faces in a close-up style. In this way, the images of women in the paintings and the meaning attributed to them by the orientalist view—as women who were desired and waiting to be possessed—was literally shattered. She also criticized the orientalist approach in her 1999 Reinforcement Series for Oriental Fantasies.12 Here she enlarged details taken from orientalist paintings by the French artist Gérome and presented them side by side as double images removed from their contexts to create an ironic reference to this outdated, outmoded view of women.

Karamustafa continues to explore this theme in recent works such as Anti-Hamam Confessions (2010), a video presenting the hamam (Turkish bath), a common subject of orientalist painters, in such a way as to turn western fantasies upside down. To deconstruct (and destroy) the orientalist view of the Turkish bath, she used a historic bath building in Tahtakale in Istanbul, designed by the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, which resembles neither the hamams represented in orientalist paintings nor the modern hamams used by tourists. For an installation titled Etiquette (2011; Fig. 4), also on this theme, the starting point was a 1933 book in the Ottoman language in which French-style etiquette was applied to Turkish society. Karamustafa prepared a dinner table based on illustrations showing proper western-style table settings with glasses, plates, and napkins. Most of the table was white, except for gold leaf designs on the plates and glasses to give the idea of an upper-class table. The western style clothes and attitudes of the male and female figures in the pictures on the labels seem far removed from the Turkish society of that era, and reflect the idea of a “nowhere” society stuck between Ottoman traditions and modern (1930s) Turkey.

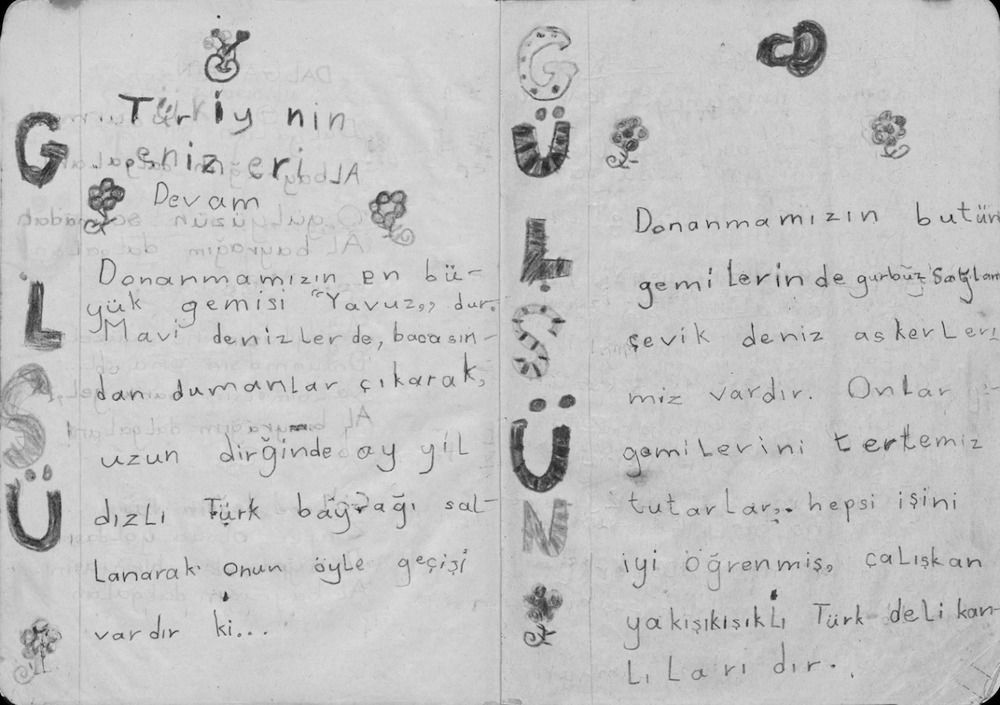

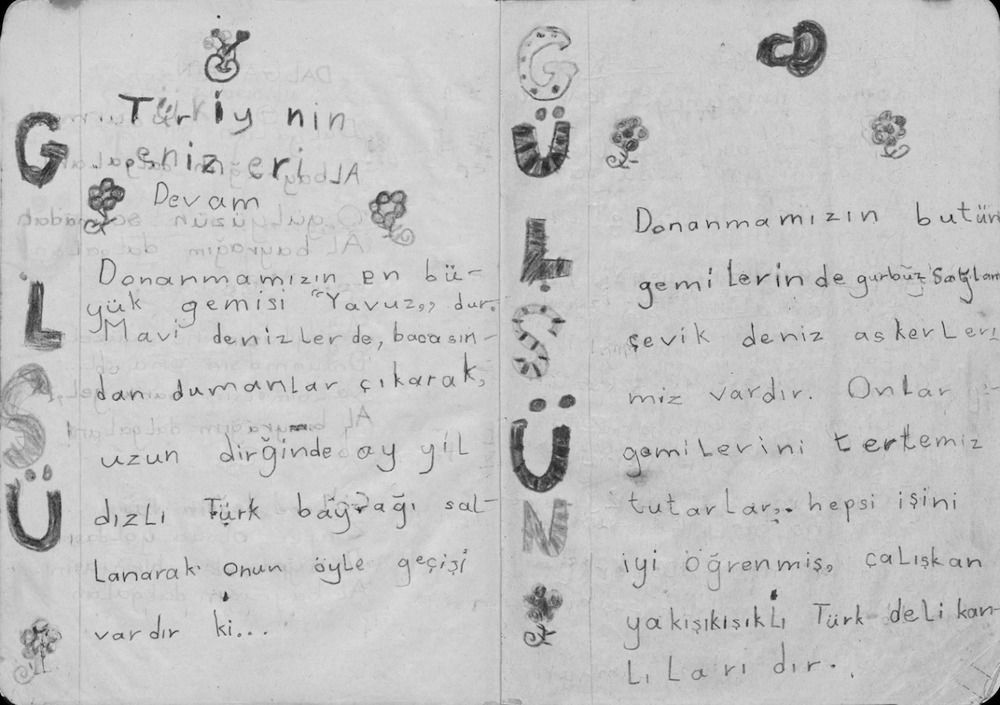

During the 1990s, Karamustafa presented works in which she used personal objects and images to relate her own experiences to the social transformations she had witnessed. As she questioned concepts of time, memory, and migration on the basis of her own personal history, she superimposed social issues using her autobiography like a “personal healer.”13 For The Notebook (1993; Pl. 10 & Fig. 5), the first of these works, she used her primary school notebook from 1953–54. In it were sentences dictated by her teacher imparting militaristic ideas, for example, “Soldiers protect the borders and they use their bodies as shields in order to protect the country.” The pages also were filled with colorful flowers and decorative letters spelling her name. For the installation, she hung photographs of herself as a child over the notebook on the wall of the exhibition hall. By emphasizing the contrast between the flowers and militaristic sentences, she drew attention to the clash between the tough prescriptivism and childhood innocence. My Roses My Reveries (1998) again used a photograph from the 1950s, this one showing her saying goodbye to her father, who was going off on a business trip and looking back at her from a train window. The digitally enlarged photograph (118” x 75”) was placed in a wide niche of the Maçka Art Gallery (Istanbul), where viewers could feel the mood of that moment, of a child being separated from her father because of his job. On the exterior of the building, on the inside walls, and on the ceramic floor tiles, the artist distributed popular rhyme couplets from poems of that era that were easy to remember. The exhibition space was used like a playground and elicited various readings.

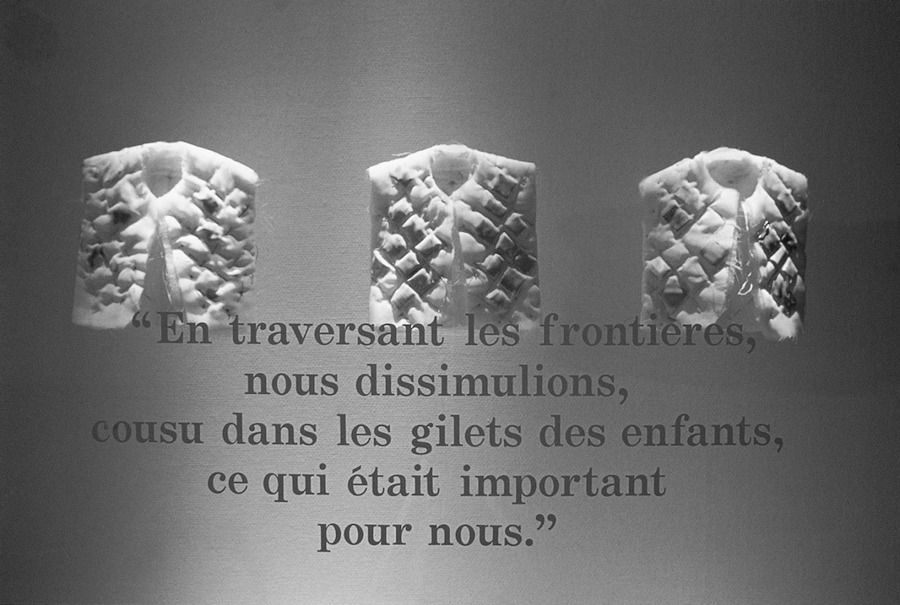

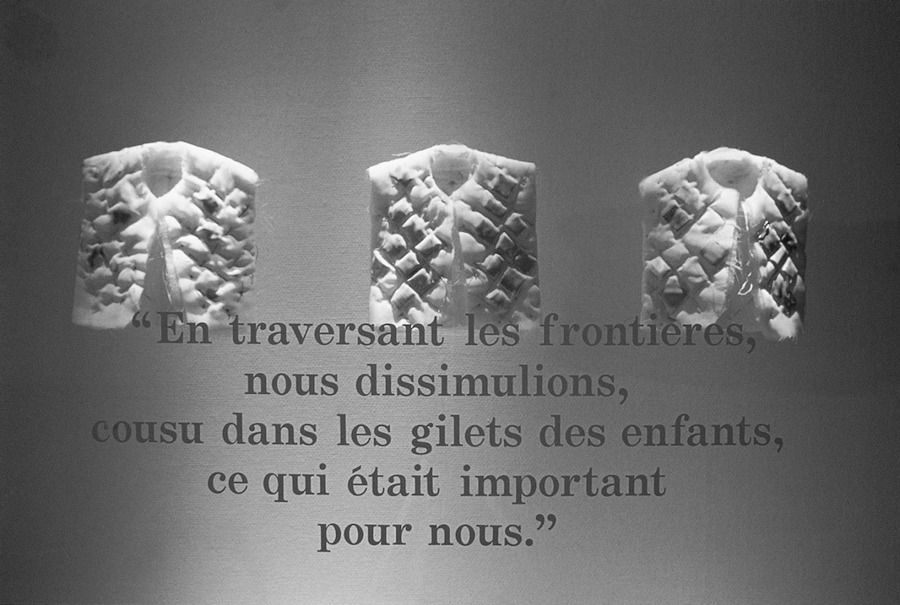

Karamustafa’s grandmother was among the thousands of Ottoman Turks who were forced to migrate from Bulgaria to Turkey in 1893, during the nationalistic upheavals in the Balkans.14 She once told Karamustafa, “As we were crossing the borders, we hid our important belongings in the inner pockets of the children’s [shirt] waists.” This became the basis of Courier (1991; Fig. 6a-b).15 Small, folded papers with writing on them were placed on children’s shirts, which were mounted on clear Plexiglass stands. Referencing her grandmother’s memory, she was stating that people who belong nowhere carried what they could on their bodies and in their clothes. This installation, which resembled a mausoleum, transformed the artist’s personal memory into social consciousness. For an exhibition in Canada, she added two items of clothing to the work. These were sewn completely closed so that they could not be worn and stood for the country that people had to leave with no chance of returning; these were hung on the wall beside a photograph of her grandmother.

A related piece, The Settler (2003), also very personal, appeared in an exhibition titled “Blood&Honey.” Translated into Turkish as “Kan&Bal,” when the two words are reversed, it becomes Bal&Kan, a reference to the Balkan region. This exhibition dealt with the socio-political events in the Balkans.16 Karamustafa’s work related to the issue in terms of her family’s migration, addressing social issues such as forced migration and the population exchange based on her personal history. This work comprised two videos with nineteenth-century picture postcards as backgrounds—of Bulgaria in the first video, and Turkey in the second. In each, women wearing folkloric clothes typical of their culture look happy at first. As they become sad, the colors fade and the furnishings change, and after awhile they must leave their home country and move on to the “other side.” The other side is a place where they can never feel at home although they now must live there.

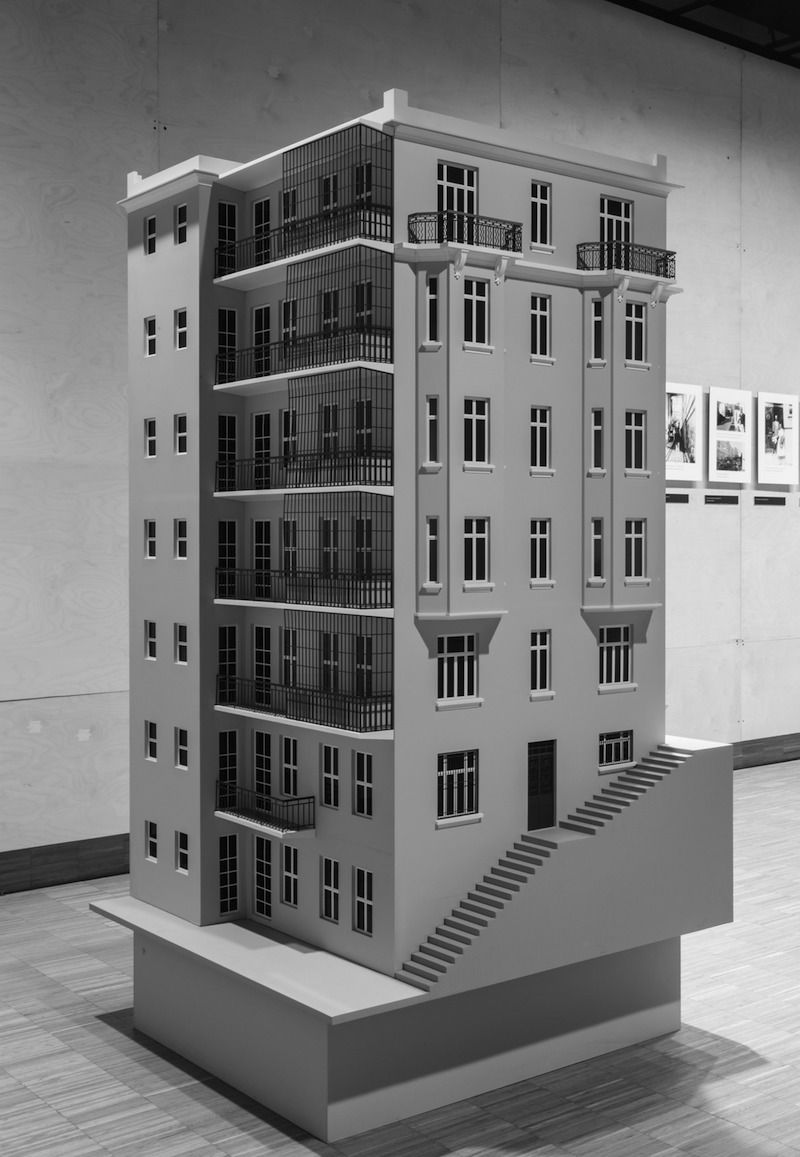

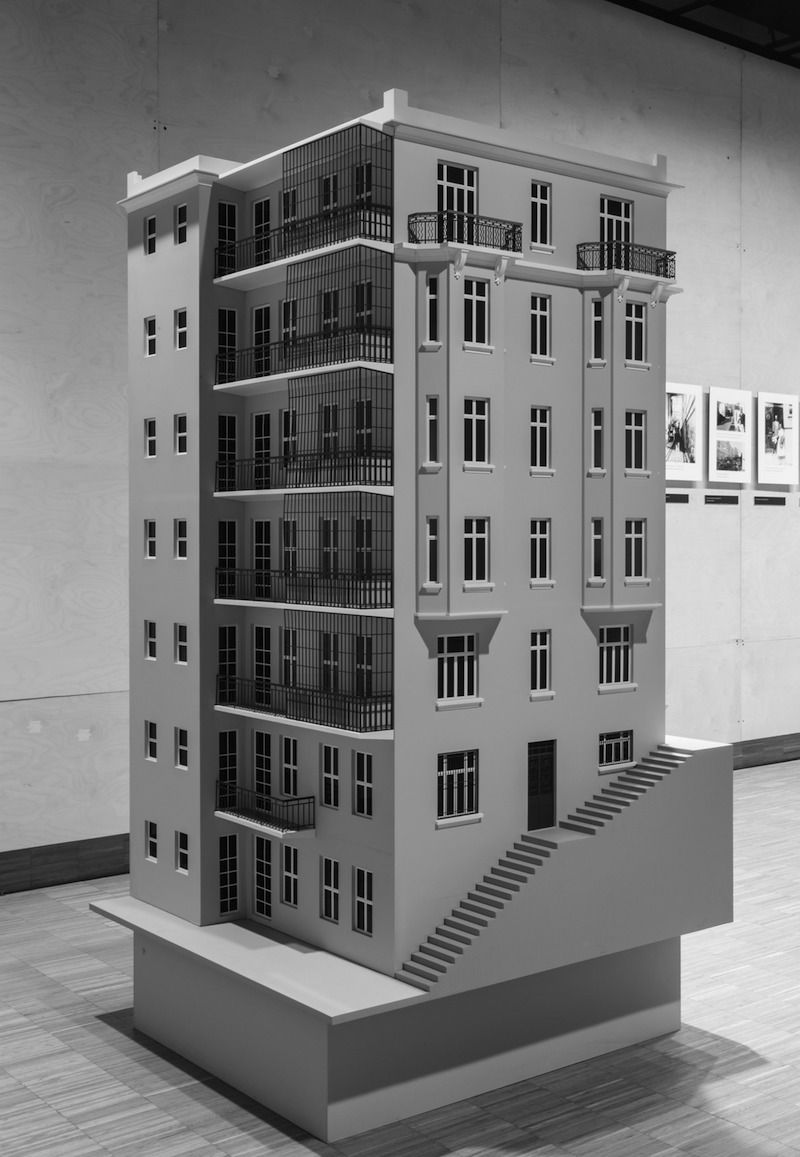

The Apartment Building (2012; Fig. 7) is based on the building where Karamustafa has lived since 1991. Located in Cihangir, one of the most popular areas in Istanbul, it was built in 1931 by a Greek family named Vaslamatzis, which later fled to Greece after nationalist attacks against Greek, Armenian, and Jewish citizens in Turkey during September 6–7, 1955. The artist was very much affected by their migration story and prepared her work as a “gift” to the Vaslamatzis family, whom she had met from time to time. She made a model of the building, almost two meters tall, which she delivered to the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, where the model was placed in the center of a room surrounded by wall photographs, including images depicting the story of the family and some of the events of September 6–7. With this “symbolic act of return,”17 Karamustafa underlined the idea that we should face history and not bury it, since the nationalistic attacks during the events of September 1955 and their consequences were rarely recognized in the history of modern Turkey.

Women and gender roles is the third major theme which Gülsün Karamustafa has confronted. Neworientation (1995; Pl. 11) remembers the prostitutes of the Galata neighborhood who met the sailors as their ships came into port, and the women in Istanbul listed in official police records as “Missing.”18 For the Fourth Istanbul Biennial, the work was exhibited in storehouse number 3 at Salıpazarı (today’s Istanbul Modern Museum), which was located close to the brothel. Reflecting the excitement of their first encounters with the incoming sailors, Karamustafa used flying ribbons to symbolize the Galata women. By also incorporating personal records of “missing” women on the ribbons, she referenced both the brothel and the individual women. She researched police records and stamped on the ribbons their initials and the dates they were “lost.”

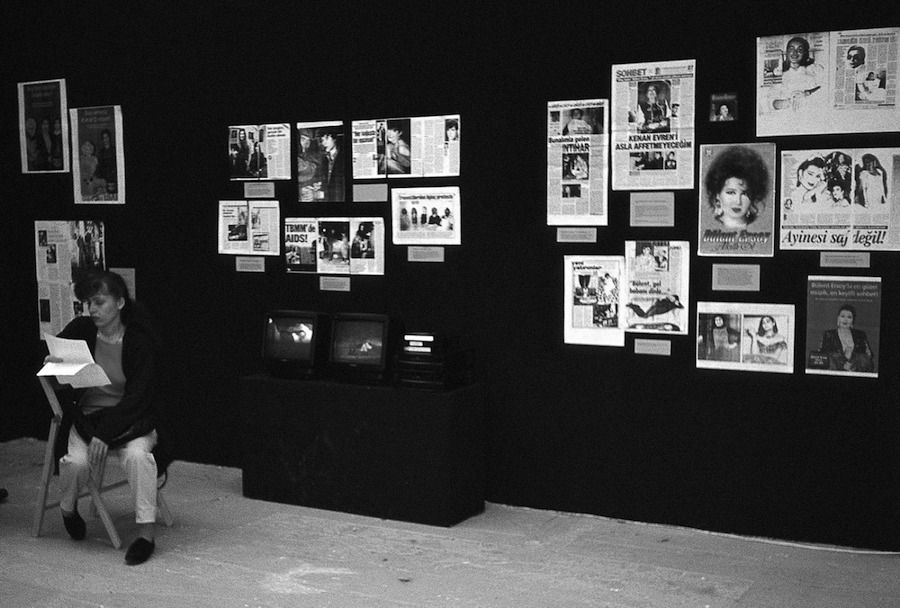

In 1996, Karamustafa was one of eight women from different professions—including a sociologist, film director, textile supplier, and other artists—to collaborate on a project titled “Culture/A Portrait of Gender from Istanbul,” focusing primarily on migration, feminism, and identity.19 Karamustafa’s video contribution, A Playground in the Net of Gendered Relations (Fig. 8), was about the very popular shows of transsexuals and transvestites on Turkish television at the time. Two monitors played simultaneously, one showing the singer Bülent Ersoy, and the other the singer and showman Huysuz Virjin. Their popularity indicated that, despite viewers’ varying backgrounds (religion, gender, culture, etc.), they liked these shows. Karamustafa wrote that, “In an environment where transvestites and transsexuals struggled for their life under brutal conditions and had to organize to defend their rights, the popular interest of both men and women in these shows revealed the social hypocrisy towards transvestites and transsexuals.”20 The artist wanted her piece to expose the hypocrisy of their situation. The television programs did not show the real lives of transvestites and transsexuals, which were lived under very different conditions in which they were exposed to violence and exclusion and suffered discrimination. Her piece was intended to point up the fact that these kinds of shows were not reflective of real life but rather “playgrounds” where actors played. Similarly, for Unconsolidated Visions (1998; Fig. 9) she presented close-up photographs of transvestites and transsexuals taken in Istanbul and Valencia, Spain. Referring to the tradition of painting the underside of Spanish balconies, she installed these photographs on the undersides of balconies of a Roman theatre in Sagunto. Her choice of location, said Karamustafa, was that balconies are “inter-locations”; they are neither inside nor outside, like transvestites.

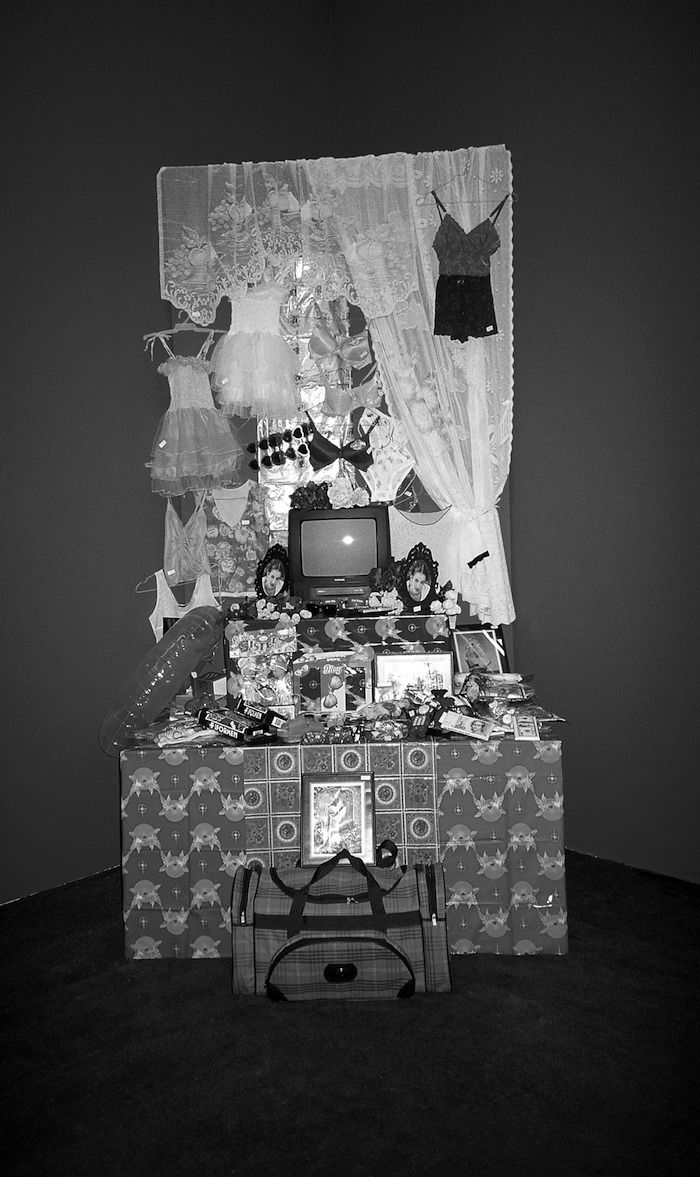

The place of women in a changing world is of great importance to Karamustafa, and a symbolic catalyst for change was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Her performance piece titled Objects of Desire, Suitcase Trading (Limit 100 Dollars) (1998, Fig. 10)21 was about the emerging issues in the aftermath. Economically challenged women from Romania, Moldavia, Russia, and elsewhere traveled to Turkey carrying suitcases filled with goods to sell. They brought goods from home as if they were their personal belongings, and refilled their empty suitcases with cheap Turkish products to market back home. The cycle, known as suitcase trading, continued for a long time as part of an informal economy. Because the practice was very profitable, some women sold their bodies to earn money to use as capital, and as prostitution increased, suitcase trading became a large operation run by various crime organizations. In Objects of Desire, Suitcase Trading (Limit 100 Dollars) Karamustafa referred to both women and goods as similar objects of desire. Women can be bought and sold; they can be exchanged in order to buy another object. The artist set out to experience suitcase trading personally and started her project with 100 dollars, as this was the least amount paid for prostitutes in that period. She used the money to purchase various objects such as music boxes, artificial flowers, men’s and women’s underwear, makeup kits, and plastic kitchen equipment to take across the border. She opened a stall at each city she visited and documented the objects she sold with Polaroid photographs and placed them next to the stall. She added a movie showing markets in Istanbul. Karamustafa also met with different consumer groups to examine the differences in habits and preferences in different locations. Unawarded Performances (2005), a film made for the “Projekt Migration” exhibition in Köln, describes another group of women from Eastern Europe who came to Turkey after the fall of the Berlin Wall. These highly educated women, who had good lives before the crisis, tell about their experiences in Istanbul working as nannies, sick-nurses, or housekeepers.

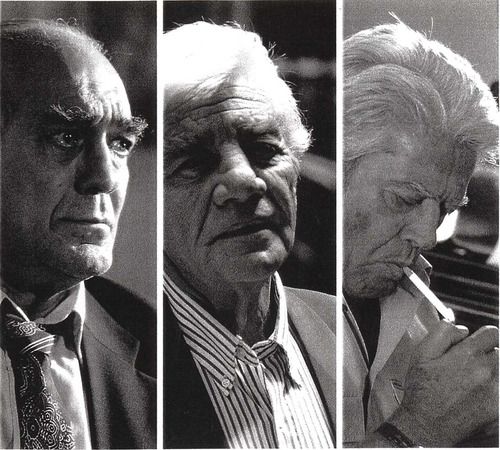

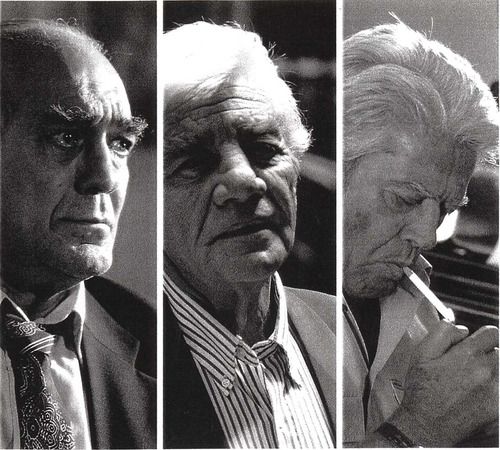

At the same time that women’s lives were changing, they were staying the same. In her video Personal Time Quartet (1999), she used her house as the location and showed a girl in various acts: arranging clothes, folding clothes, skipping rope, polishing her nails, etc., all actions typically attributed to women. The unifying theme was the unchangeableness of typical women’s roles despite the various cultures and geographies that shape the female identity. In another video series, Men Crying (2001; Fig. 11) she dealt with the gender roles attributed to men. In collaboration with Atıf Yılmaz,22 she recorded three important actors of Turkey in 1960s and 1970s crying after they were left by their lovers. The videos were meant to contradict the common expression, “men don’t cry.”

It can be said that Karamustafa’s works are generally based on the idea of the outcast, namely “the other”: it might be a person who is forced to migrate, someone who is not easily defined in terms of gender or who is different, or who is “the other” as a woman. An analysis of her oeuvre reveals that she addresses the determined, solid, and masculine form of modernity through other identities. For example, her video Tailor Made (2005; Fig. 12) shows singers and belly dancers in pavilions and nightclubs walking on a runway like supermodels. At the same time she makes an analogy between the club stages and fashion runways, she also draws attention to the contradiction between what is seen on the runway and the lives lived behind that stage.

Gülsün Karamustafa began her career in 1980 as a painter but throughout her career she has created a variety of works using her strong observation skills and intellectual richness. Although varying in theme and medium, each of her works intertwines with another and presents continuity as she deals with concepts that broaden with each work. In her own words: “I can say that each of my works is within another, it is as if one work is opening up and explaining another.”23

The artist is clear and direct when presenting works that are based on her memories, and she has the ability to capture the moment where these reminiscences have universal reach. The concepts she explores are related in that they reflect social transformations and changes in terms of contradictions and contrasts, as when she draws attention to the problem of identity resulting from hybridization after migration by relating this to the concept of kitsch and the uncertainties in identity, gender, and boundaries within the process of globalization. While she has exhibited her works in many places in Europe, the place that sustains her is Turkey, especially her cultural environment of Istanbul, where she is influenced by the cultural paradigms that form it and the synthesis/hybridities created by these paradigms. In Istanbul, which is both a bridge and a geographic point of separation between East and West, the mix of religious, political, and cultural contrasts, contradictions and hybridities inform her work, and one could say that Istanbul is the hybrid which is central to Gülsün Karamustafa’s art.

- - -

Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler and Tuna Şare are Assistant Professors of Art History at Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University in Turkey. Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler teaches courses on modern and contemporary art and has published several articles and a book on contemporary art in Turkey. Tuna Şare, a recent Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, is currently focusing on female musicians in classical art.

Originally published in Woman’s Art Journal, “Gülsün Karamustafa: A Vagabond, From Personal to Social, From Local to Global”, by Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler and Tuna Şare, Vol. 35, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2014).

Born in Turkey to a middle-class family, Karamustafa’s father was a prominent radio host. She spent her early childhood in Ankara, where she received her early education in painting. Later, with the support of her family she studied painting at Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts, graduating in 1969. As a painter, art director, and contemporary artist, she has witnessed the political events and economic upheavals that have done and continue to shape modern Turkey. Internal migration waves, especially from rural Central and Eastern Anatolia to urban cities like Istanbul and Ankara, started in Turkey in the 1950s. The military coups of 1971 and 1980, and their reforms were significant breaking points in Turkey.2 After 1980, the application of neo-liberal policies and the intensity of militarist discourse affected artists, including Karamustafa, who tried to overcome feelings of being caught up in these issues by “taking refuge in production.”3 The following decade, after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, was marked by an external wave of migration to Turkey from economically challenged Eastern Bloc countries and Russia. It can be said that Karamustafa’s forty-year art career was formed by coups and socio-political changes in Turkey and their intersections with her personal history.

Thematically, Karamustafa’s works fall into three main categories. First are her works that deal with the concepts of migration, identity, hybridism, memory, and boundaries. In the second category are works that explore her personal history and her own experiences as they relate to those themes in the first category. Finally, there are works about gender roles and femininity. Her works also can be classified based on their different materials, techniques, and methods. She uses many mediums in her works and installations, including canvas, ready-made objects, photographs, and video. Her first major experience in film, as the art director of the film “Bir Yudum Sevgi” (A Sip of Love) (1984), directed by the prominent Turkish film director Atıf Yılmaz,4 greatly influenced her future work. Although her later video projects may have different themes, they carry the traces of such earlier experiences with cinema.

The ambiguity of boundaries through the concept of migration and hybrid situations formed as a result of migration is one of Karamustafa’s frequent themes. She has discussed different kinds of boundaries—cultural, sexual, and territorial—and through her work has tried to show the hybridities within these boundaries.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the artist questioned and interpreted social and cultural events first in paintings and later in tapestries. She combined sacred images belonging to different cultures and time frames, and used Istanbul as a bridge for uniting West and East. She incorporated items of kitsch in her works to reflect the cultural corruption that occurred as a result of internal migrations in the 1970s and 1980s, especially from rural eastern Turkey to the western cities. By 1985, these kitsch images had become three-dimensional objects aimed at revealing information about Turkey as a new Arab-influenced lifestyle was becoming increasingly popular and a hybrid culture was being formed by people that had migrated to the cities.

Fig. 2. Gülsün Karamustafa, Stairway (2001), video still, 4’46”. Im Zeichen Der Stadt, Kunstmuseum, Bonn.

Although Karamustafa included kitsch objects as they are in everyday life, she distanced herself from these materials to evoke various interpretations. For example, in Mystic Transport (1992; PI. 7 & Fig. 1),5 colorful blankets in large baskets typically used for moving made reference to the lives of people who had to migrate but belonged nowhere. The migration theme reoccurs in several works that were exhibited in international shows. Heitmat Ist wo Mann Isst (Homeland is not where you are born, but the place that feeds you) (1994)6 consisted of three pieces of spoons wrapped in gauze and under which was written “Heimat Ist wo Mann Isst.” For her video Stairway (2001; Fig. 2), she recorded the work conditions of a group of gypsy children who had migrated from Eastern Europe. The “stairway” of the video was built in the 1850s by Abraham Salomon Kamondo, an important Jewish broker of Istanbul’s Karaköy district. The children made music and collected money at this spot. They had come with their families for three months (the length of their visas) to Istanbul, where they lived in poor conditions and earned money before having to return to their home countries.

Related to the concept of migration is hybridization, and among Karamustafa’s works on this theme is Genealogy (1994; Pl. 8). While searching for the identity of Zeynep Sultan, an Ottoman princess, for a movie project for the Turkish Radioand Television Corporation (TRT), she found the Sultan family tree, which inspired this work. She listed the royal women’s birth names and their Ottoman names, given to them when they became members of the Ottoman harem; she showed that Byzantine names such as Asporça, Efrandize and Halifira were replaced in time by Islamic names such as Hüsnümelek, Nevfidan, and Hayrandil. She placed ribbons on a small piece of acetate, referring to these women by name. Karamustafa tried to present the place of women in Ottoman culture through a sociological approach. There was tension over the differences in names between Ottoman emperors’ wives, whose names had meanings about their beauty, and their daughters, whose names were mostly taken from Koran. The artist said that her work was “based on the observation of legitimacy.”7

Fig. 3. Gülsün Karamustafa, Postposition (1995), textile collage, 5 pieces, each 49 ¼” x 39 3/8”. Foreign Services Exhibition, Shedhalle, Zurich

For another work about cultural hybridization, Postposition (1995; Fig. 3),8 five framed tapestries were presented as Byzantine icons.9 Although displayed as carpet-like objects typical of a predominantly Muslim society, these tapestries incorporated religious and cultural motifs belonging to Christianity and Western society, such as the images of Christ as a shepherd and Elvis Presley.

The relationship between the center, the periphery, and postcolonial approaches in art was the theme of Presentation of an Early Representation (1996) and Trellis of My Mind (1998).10 Trellis of My Mind presented overlapping Jewish, Christian, and Islamic images and writings as if they represented a single religion. Other artists in this exhibition included Ghada Amer, Mona Hatoum, and Shirin Neshat, all of whom have become well known in the West. Presentation of an Early Representation was based on a sixteenth-century watercolor by an anonymous German painter that, despite its early date, resembled the orientalist paintings of the nineteenth century. In Karamustafa’s painting, European women, including a black woman, appear as if they are in a slave market, where eastern men are choosing women by touching their breasts or putting their hands under the women’s skirts. Her painting carries almost all of the elements of an orientalist painting, but by basing her work on a sixteenth-century work that represents a much earlier western outlook towards the East, Karamustafa is questioning the eastern identity as presented by a westerner.

A later work, Fragmenting/Fragments (1999; Pl. 9),11 is about the deconstruction of this orientalist view. Karamustafa reproduced female figures from nineteenth-century orientalist paintings and then cut them into pieces and recombined the fragments. She combined feet, breasts, hands, and pieces of faces in a close-up style. In this way, the images of women in the paintings and the meaning attributed to them by the orientalist view—as women who were desired and waiting to be possessed—was literally shattered. She also criticized the orientalist approach in her 1999 Reinforcement Series for Oriental Fantasies.12 Here she enlarged details taken from orientalist paintings by the French artist Gérome and presented them side by side as double images removed from their contexts to create an ironic reference to this outdated, outmoded view of women.

Fig. 4. Gülsün Karamustafa, Etiquette (2011), mixed media installation. Solo für … Exhibition, IFA Gallery, Stuttgart.

Karamustafa continues to explore this theme in recent works such as Anti-Hamam Confessions (2010), a video presenting the hamam (Turkish bath), a common subject of orientalist painters, in such a way as to turn western fantasies upside down. To deconstruct (and destroy) the orientalist view of the Turkish bath, she used a historic bath building in Tahtakale in Istanbul, designed by the Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, which resembles neither the hamams represented in orientalist paintings nor the modern hamams used by tourists. For an installation titled Etiquette (2011; Fig. 4), also on this theme, the starting point was a 1933 book in the Ottoman language in which French-style etiquette was applied to Turkish society. Karamustafa prepared a dinner table based on illustrations showing proper western-style table settings with glasses, plates, and napkins. Most of the table was white, except for gold leaf designs on the plates and glasses to give the idea of an upper-class table. The western style clothes and attitudes of the male and female figures in the pictures on the labels seem far removed from the Turkish society of that era, and reflect the idea of a “nowhere” society stuck between Ottoman traditions and modern (1930s) Turkey.

Fig. 5. Gülsün Karamustafa, The Notebook (1993), detail. Kadın Eserleri Kütüphanesi ve Bilgi Merkezi Vakfı (Women’s Library and Information Center Foundation), Istanbul.

During the 1990s, Karamustafa presented works in which she used personal objects and images to relate her own experiences to the social transformations she had witnessed. As she questioned concepts of time, memory, and migration on the basis of her own personal history, she superimposed social issues using her autobiography like a “personal healer.”13 For The Notebook (1993; Pl. 10 & Fig. 5), the first of these works, she used her primary school notebook from 1953–54. In it were sentences dictated by her teacher imparting militaristic ideas, for example, “Soldiers protect the borders and they use their bodies as shields in order to protect the country.” The pages also were filled with colorful flowers and decorative letters spelling her name. For the installation, she hung photographs of herself as a child over the notebook on the wall of the exhibition hall. By emphasizing the contrast between the flowers and militaristic sentences, she drew attention to the clash between the tough prescriptivism and childhood innocence. My Roses My Reveries (1998) again used a photograph from the 1950s, this one showing her saying goodbye to her father, who was going off on a business trip and looking back at her from a train window. The digitally enlarged photograph (118” x 75”) was placed in a wide niche of the Maçka Art Gallery (Istanbul), where viewers could feel the mood of that moment, of a child being separated from her father because of his job. On the exterior of the building, on the inside walls, and on the ceramic floor tiles, the artist distributed popular rhyme couplets from poems of that era that were easy to remember. The exhibition space was used like a playground and elicited various readings.

Fig. 6a. (L.) Gülsün Karamustafa, Courier (1991), mixed media installation, 3 pieces, each 15 ¾” x 15 ¾”. Memory/Recollection Exhibition, Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul. 6b. (R.) detail.

Fig. 6a. (L.) Gülsün Karamustafa, Courier (1991), mixed media installation, 3 pieces, each 15 ¾” x 15 ¾”. Memory/Recollection Exhibition, Taksim Art Gallery, Istanbul. 6b. (R.) detail.

Karamustafa’s grandmother was among the thousands of Ottoman Turks who were forced to migrate from Bulgaria to Turkey in 1893, during the nationalistic upheavals in the Balkans.14 She once told Karamustafa, “As we were crossing the borders, we hid our important belongings in the inner pockets of the children’s [shirt] waists.” This became the basis of Courier (1991; Fig. 6a-b).15 Small, folded papers with writing on them were placed on children’s shirts, which were mounted on clear Plexiglass stands. Referencing her grandmother’s memory, she was stating that people who belong nowhere carried what they could on their bodies and in their clothes. This installation, which resembled a mausoleum, transformed the artist’s personal memory into social consciousness. For an exhibition in Canada, she added two items of clothing to the work. These were sewn completely closed so that they could not be worn and stood for the country that people had to leave with no chance of returning; these were hung on the wall beside a photograph of her grandmother.

A related piece, The Settler (2003), also very personal, appeared in an exhibition titled “Blood&Honey.” Translated into Turkish as “Kan&Bal,” when the two words are reversed, it becomes Bal&Kan, a reference to the Balkan region. This exhibition dealt with the socio-political events in the Balkans.16 Karamustafa’s work related to the issue in terms of her family’s migration, addressing social issues such as forced migration and the population exchange based on her personal history. This work comprised two videos with nineteenth-century picture postcards as backgrounds—of Bulgaria in the first video, and Turkey in the second. In each, women wearing folkloric clothes typical of their culture look happy at first. As they become sad, the colors fade and the furnishings change, and after awhile they must leave their home country and move on to the “other side.” The other side is a place where they can never feel at home although they now must live there.

Fig. 7. Gülsün Karamustafa, The Apartment Building (2012), mixed media installation. A Promised Exhibition, SALT Beyoğlu, Istanbul.

The Apartment Building (2012; Fig. 7) is based on the building where Karamustafa has lived since 1991. Located in Cihangir, one of the most popular areas in Istanbul, it was built in 1931 by a Greek family named Vaslamatzis, which later fled to Greece after nationalist attacks against Greek, Armenian, and Jewish citizens in Turkey during September 6–7, 1955. The artist was very much affected by their migration story and prepared her work as a “gift” to the Vaslamatzis family, whom she had met from time to time. She made a model of the building, almost two meters tall, which she delivered to the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, where the model was placed in the center of a room surrounded by wall photographs, including images depicting the story of the family and some of the events of September 6–7. With this “symbolic act of return,”17 Karamustafa underlined the idea that we should face history and not bury it, since the nationalistic attacks during the events of September 1955 and their consequences were rarely recognized in the history of modern Turkey.

Women and gender roles is the third major theme which Gülsün Karamustafa has confronted. Neworientation (1995; Pl. 11) remembers the prostitutes of the Galata neighborhood who met the sailors as their ships came into port, and the women in Istanbul listed in official police records as “Missing.”18 For the Fourth Istanbul Biennial, the work was exhibited in storehouse number 3 at Salıpazarı (today’s Istanbul Modern Museum), which was located close to the brothel. Reflecting the excitement of their first encounters with the incoming sailors, Karamustafa used flying ribbons to symbolize the Galata women. By also incorporating personal records of “missing” women on the ribbons, she referenced both the brothel and the individual women. She researched police records and stamped on the ribbons their initials and the dates they were “lost.”

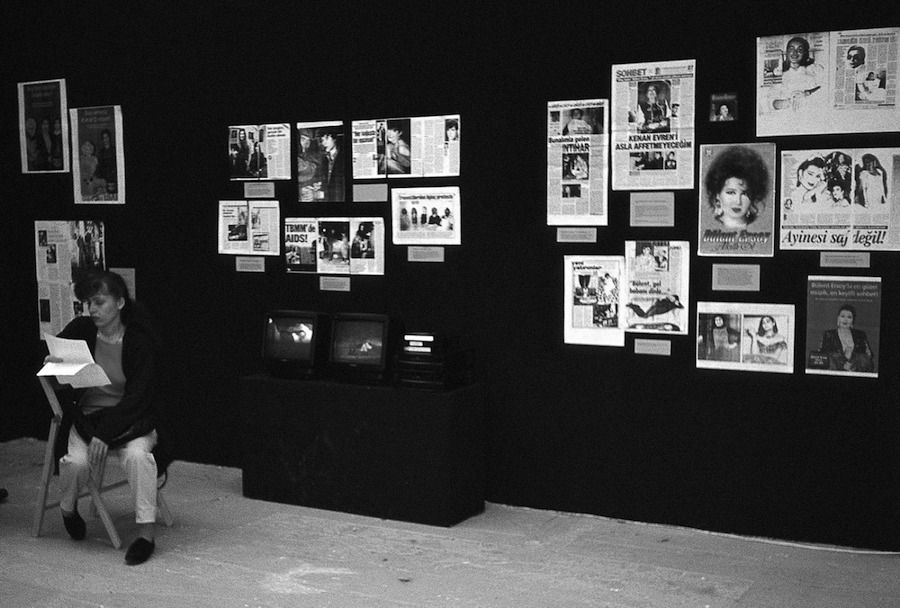

Fig. 8. Gülsün Karamustafa, A Playground in the Net of Gendered Relations (1996), mixed media and video installation. Kültür–Shedhalle, Zurich.

Fig. 9. Gülsün Karamustafa, Unconsolidated Visions (1998), laser printing, 9 pieces, dimensions vary. Roman Theatre, Sagunto, Valencia.

In 1996, Karamustafa was one of eight women from different professions—including a sociologist, film director, textile supplier, and other artists—to collaborate on a project titled “Culture/A Portrait of Gender from Istanbul,” focusing primarily on migration, feminism, and identity.19 Karamustafa’s video contribution, A Playground in the Net of Gendered Relations (Fig. 8), was about the very popular shows of transsexuals and transvestites on Turkish television at the time. Two monitors played simultaneously, one showing the singer Bülent Ersoy, and the other the singer and showman Huysuz Virjin. Their popularity indicated that, despite viewers’ varying backgrounds (religion, gender, culture, etc.), they liked these shows. Karamustafa wrote that, “In an environment where transvestites and transsexuals struggled for their life under brutal conditions and had to organize to defend their rights, the popular interest of both men and women in these shows revealed the social hypocrisy towards transvestites and transsexuals.”20 The artist wanted her piece to expose the hypocrisy of their situation. The television programs did not show the real lives of transvestites and transsexuals, which were lived under very different conditions in which they were exposed to violence and exclusion and suffered discrimination. Her piece was intended to point up the fact that these kinds of shows were not reflective of real life but rather “playgrounds” where actors played. Similarly, for Unconsolidated Visions (1998; Fig. 9) she presented close-up photographs of transvestites and transsexuals taken in Istanbul and Valencia, Spain. Referring to the tradition of painting the underside of Spanish balconies, she installed these photographs on the undersides of balconies of a Roman theatre in Sagunto. Her choice of location, said Karamustafa, was that balconies are “inter-locations”; they are neither inside nor outside, like transvestites.

Fig. 10. Gülsün Karamustafa, Objects of Desire, Suitcase Trading (Limit 100 Dollars) (1998), performance. Money-Nation Exhibition, Shedhalle, Zurich.

The place of women in a changing world is of great importance to Karamustafa, and a symbolic catalyst for change was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Her performance piece titled Objects of Desire, Suitcase Trading (Limit 100 Dollars) (1998, Fig. 10)21 was about the emerging issues in the aftermath. Economically challenged women from Romania, Moldavia, Russia, and elsewhere traveled to Turkey carrying suitcases filled with goods to sell. They brought goods from home as if they were their personal belongings, and refilled their empty suitcases with cheap Turkish products to market back home. The cycle, known as suitcase trading, continued for a long time as part of an informal economy. Because the practice was very profitable, some women sold their bodies to earn money to use as capital, and as prostitution increased, suitcase trading became a large operation run by various crime organizations. In Objects of Desire, Suitcase Trading (Limit 100 Dollars) Karamustafa referred to both women and goods as similar objects of desire. Women can be bought and sold; they can be exchanged in order to buy another object. The artist set out to experience suitcase trading personally and started her project with 100 dollars, as this was the least amount paid for prostitutes in that period. She used the money to purchase various objects such as music boxes, artificial flowers, men’s and women’s underwear, makeup kits, and plastic kitchen equipment to take across the border. She opened a stall at each city she visited and documented the objects she sold with Polaroid photographs and placed them next to the stall. She added a movie showing markets in Istanbul. Karamustafa also met with different consumer groups to examine the differences in habits and preferences in different locations. Unawarded Performances (2005), a film made for the “Projekt Migration” exhibition in Köln, describes another group of women from Eastern Europe who came to Turkey after the fall of the Berlin Wall. These highly educated women, who had good lives before the crisis, tell about their experiences in Istanbul working as nannies, sick-nurses, or housekeepers.

Fig. 11. Gülsün Karamustafa, Men Crying (2001), 3 screen video, 3’, 1’47”, 2’16”. Proje 4L, Istanbul.

At the same time that women’s lives were changing, they were staying the same. In her video Personal Time Quartet (1999), she used her house as the location and showed a girl in various acts: arranging clothes, folding clothes, skipping rope, polishing her nails, etc., all actions typically attributed to women. The unifying theme was the unchangeableness of typical women’s roles despite the various cultures and geographies that shape the female identity. In another video series, Men Crying (2001; Fig. 11) she dealt with the gender roles attributed to men. In collaboration with Atıf Yılmaz,22 she recorded three important actors of Turkey in 1960s and 1970s crying after they were left by their lovers. The videos were meant to contradict the common expression, “men don’t cry.”

Fig. 12. Gülsün Karamustafa, Tailor Made (2005), video installation, 5’41”. Second Video Film Biennale, Mechelen.

It can be said that Karamustafa’s works are generally based on the idea of the outcast, namely “the other”: it might be a person who is forced to migrate, someone who is not easily defined in terms of gender or who is different, or who is “the other” as a woman. An analysis of her oeuvre reveals that she addresses the determined, solid, and masculine form of modernity through other identities. For example, her video Tailor Made (2005; Fig. 12) shows singers and belly dancers in pavilions and nightclubs walking on a runway like supermodels. At the same time she makes an analogy between the club stages and fashion runways, she also draws attention to the contradiction between what is seen on the runway and the lives lived behind that stage.

Gülsün Karamustafa began her career in 1980 as a painter but throughout her career she has created a variety of works using her strong observation skills and intellectual richness. Although varying in theme and medium, each of her works intertwines with another and presents continuity as she deals with concepts that broaden with each work. In her own words: “I can say that each of my works is within another, it is as if one work is opening up and explaining another.”23

The artist is clear and direct when presenting works that are based on her memories, and she has the ability to capture the moment where these reminiscences have universal reach. The concepts she explores are related in that they reflect social transformations and changes in terms of contradictions and contrasts, as when she draws attention to the problem of identity resulting from hybridization after migration by relating this to the concept of kitsch and the uncertainties in identity, gender, and boundaries within the process of globalization. While she has exhibited her works in many places in Europe, the place that sustains her is Turkey, especially her cultural environment of Istanbul, where she is influenced by the cultural paradigms that form it and the synthesis/hybridities created by these paradigms. In Istanbul, which is both a bridge and a geographic point of separation between East and West, the mix of religious, political, and cultural contrasts, contradictions and hybridities inform her work, and one could say that Istanbul is the hybrid which is central to Gülsün Karamustafa’s art.

Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler and Tuna Şare are Assistant Professors of Art History at Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University in Turkey. Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler teaches courses on modern and contemporary art and has published several articles and a book on contemporary art in Turkey. Tuna Şare, a recent Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, is currently focusing on female musicians in classical art.

Originally published in Woman’s Art Journal, “Gülsün Karamustafa: A Vagabond, From Personal to Social, From Local to Global”, by Solmaz Bunulday Hasgüler and Tuna Şare, Vol. 35, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2014).

- 1.Levent Çalıkoğlu, ed., Çağdaş Sanat Konuşmaları 3, 90'lı Yıllarda Türkiye'de Çağdaş Sanat Konuşmaları (Talks on Contemporary Art 3, Contemporary Art in Turkey in the 90s), (Istanbul: YKY, 2008), 54.

- 2.The objective of the 1971 military coup was institutional reform, and the 1980 coup was intended to reinforce the reforms of the earlier interventions. Karamustafa and her husband were sent to prison for a while after they were accused of complicity in 1971 and they were unable to obtain passports for 16 years after that time.

- 3.Barbara Heinrich, Gülsün Karamustafa, Güllerim, Tahayyüllerim, (My Roses My Reveries) (Istanbul: YKY, 2007), 16.

- 4.Karamustafa was the art director for Asılacak Kadın (Woman to Be Hanged) (1986), Kupa Kızı (Queen of Hearts) (1986), and Gecenin Öteki Yüzü (The Other Side of Night) (1987). She was also the art director for Benim Sinemalarım (My Movies) in 1990 with Firuzan.

- 5.Exhibited in the Third Istanbul Biennial, 1992.

- 6.Shown in the 1994 "İskele" (Dock) exhibition in Stuttgart's IFA Gallery.

- 7.Legitimacy is based on ancestry through the father.

- 8.Shown in the 1995 "Foreign Services" exhibition in Switzerland.

- 9.Thin carpets hang on the walls. There are pictures on these carpets and they are used for decoration.

- 10.Presentation of An Early Representation was shown in the 1996 "Inclusion/Exclusion" exhibition in Graz, and both were included in the 1998 exhibition "Echolot" in Kassel, curated by René Block.

- 11.Shown in the 1999 "Stills, Cuts, and Fragments" exhibition in Stuttgart.

- 12.Presented in the 1999 "Ulema" exhibition in Berlin.

- 13.Erden Kosova, "Gülsün Karamustafa ile Söyleşi," (Conversation with Gülsün Karamustafa), Art-ist 4 (2001): 33.

- 14.Due to nationalistic upheavals, the Balkan states of the Ottoman Empire started to declare their independence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Bulgaria, for example, declared its independence in 1908. Muslim Ottoman Turks, once living in the Balkan states, were forced to migrate to Istanbul and to other cities of Anatolia, which were still part of the Ottoman Empire and later became modern Turkey.

- 15.Deniz Şengel, "Hafıza-yı Beşer ya da 'Anı Bellek' Sergi Dizisi" (Exhibition Series on The Recollection of Memory), Arredamento Dekorasyon 34 (1992): 150-51.

- 16.In the early 19th and 20th centuries, Balkan wars and the formation of nation states led to the migration of thousands of people of various races from the Balkans to different countries. In the 20th century, the demolishing of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the nation-states also greatly affected the Balkans, this time leading to migrations of Balkan peoples to other countries of Europe due to economic challenges.

- 17.Yasemin Bay, "Apartmanı Sanat Eseri Olarak İade Etti" (She Returned the Building as an Art Object) Milliyet, February 19, 2012. Accessed on April 16, 2012.

- 18.Anonymous, "4. Uluslararası İstanbul Bienali, Paradoksal Bir Dünyada Sanatın Görünümü" (Fourth International Istanbul Biennial, Art in a Paradoxical World), Milliyet Sanat 368 (September 1995): 38-39.

- 19.Earlier, in 1987, she made a work called Double Reality, which presented a mannequin as a transvestite as a way to deconstruct the social definitions of gender. The mannequin was framed with different colored bars signifying both social and cultural references to gender identity.

- 20.Gülsün Karamustafa, "Cinsiyetlendirilmis¸ İlişkiler Ağında Bir Oyun Alanı" (A Playground in the Net of Gendered Relations)—İstanbul'dan Bir "Toplumsal Cinsiyet" Projesi (Zurich: Verlag Shedhalle Zurich, 1997), 78.

- 21.The piece was initially part of a project called "MoneyNations" (1998) that traveled to various cities of Europe (Zurich, Rennes, Hanover) during 1998-2001. She donated the money she earned to the women of the cities where she performed. After 2001, she continued to travel but changed her performance by replacing the basic goods in her suitcase with luxury items.

- 22.Karamustafa had worked with Atıf Yılmaz (one of the significant directors in Turkey) as the art director of his movie "Bir Yudum Sevgi" (A Sip of Love), in 1984.

- 23.Hüseyin Alptekin, "Gülsün Karamustafa: Kumaşlar, Melez İmajlar, Kişisel Defterler" (Gülsün Karamustafa: Textiles, Mixed Images, and Personal Notebooks), Anons 53–54 (1995), 18-19.