Seeing Rabih Mroué in Istanbul in the Aftermath of March 30th Elections

ZEYNEP ÖZ

September 15, 2014

“What is the role of the (Lebanese) left in the civil war?” is a question posed by the artist in the video installation On Three Posters: Reflections on a Video Performance by Rabih Mroué, on view at the exhibition Rabih Mroué. The question takes centerpiece as we move throughout the two exhibition venues at SALT Beyoglu and SALT Galata. It also takes centerpiece as we move through the political uncertainty in Turkey and is worth considering, as it will definitively be the question we pose to ourselves in 20 years time.

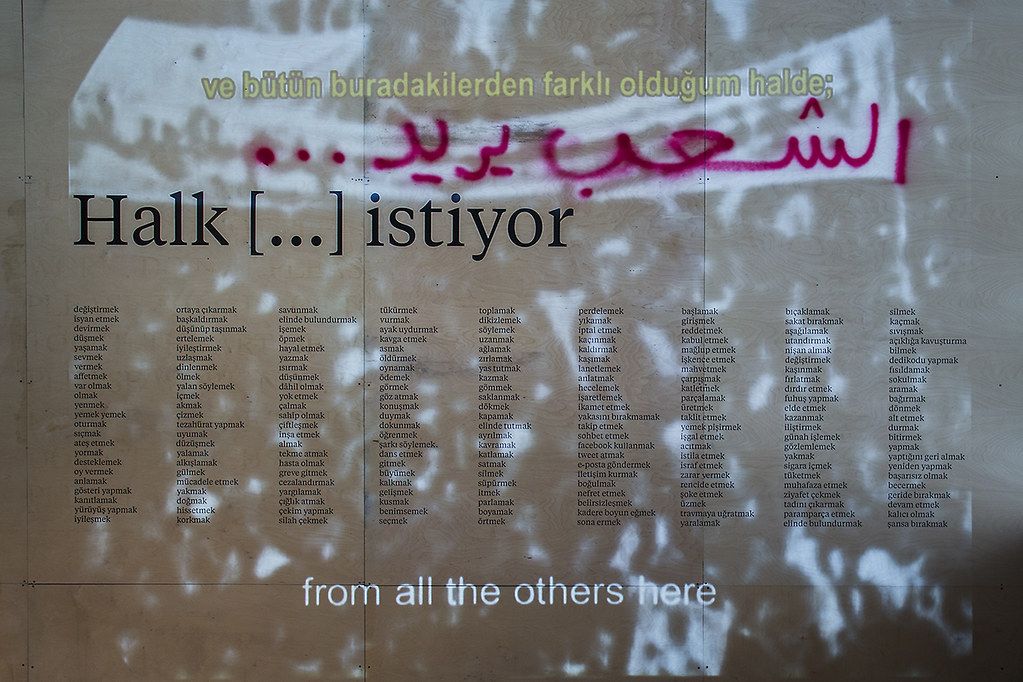

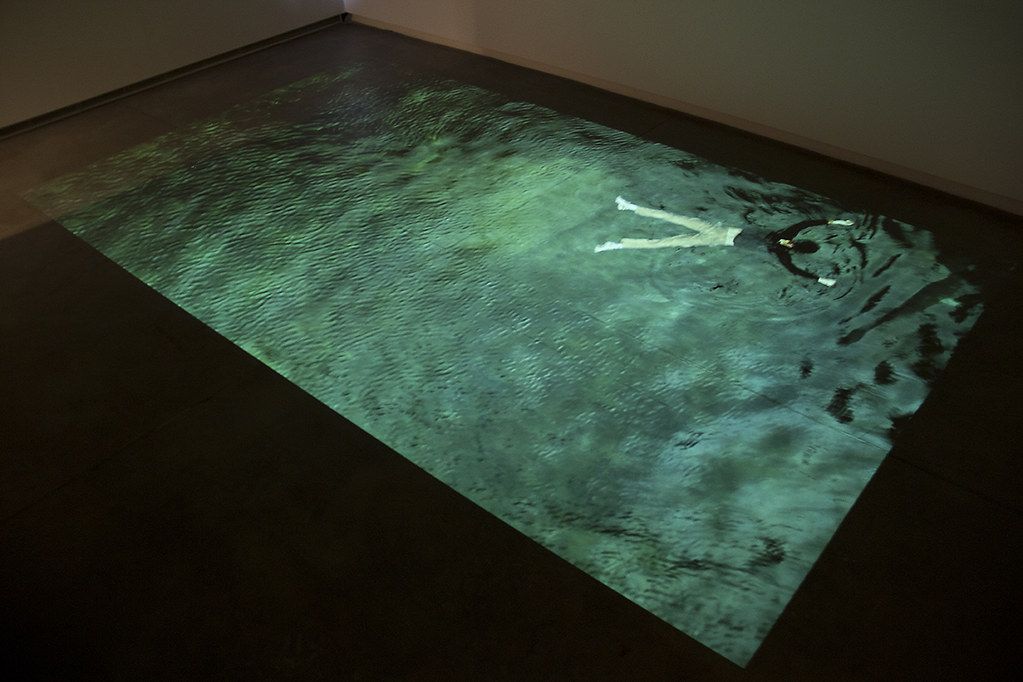

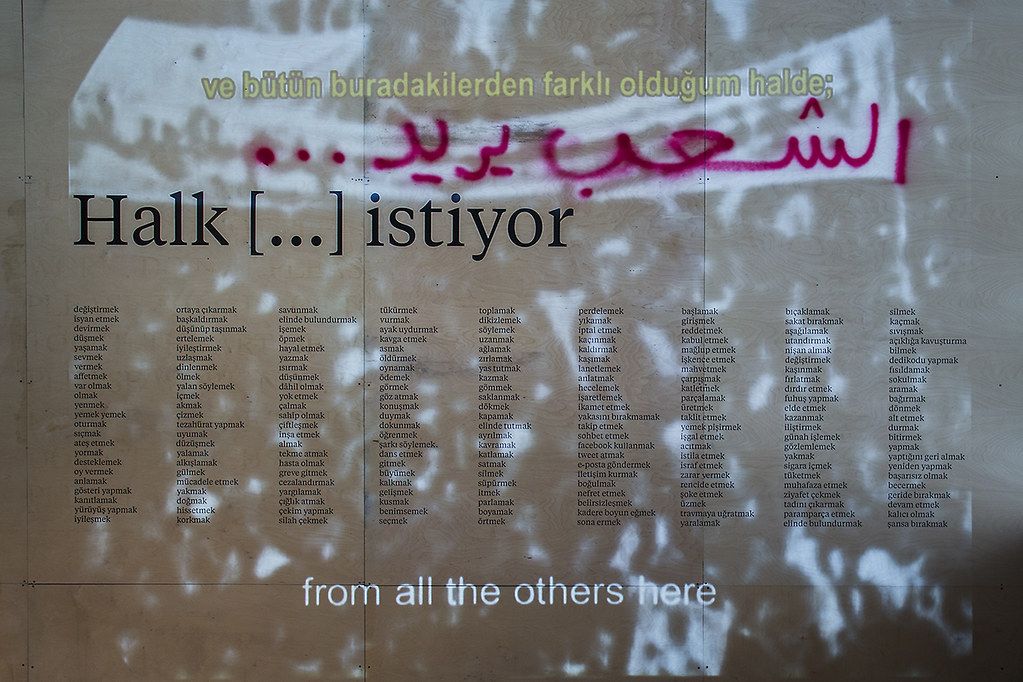

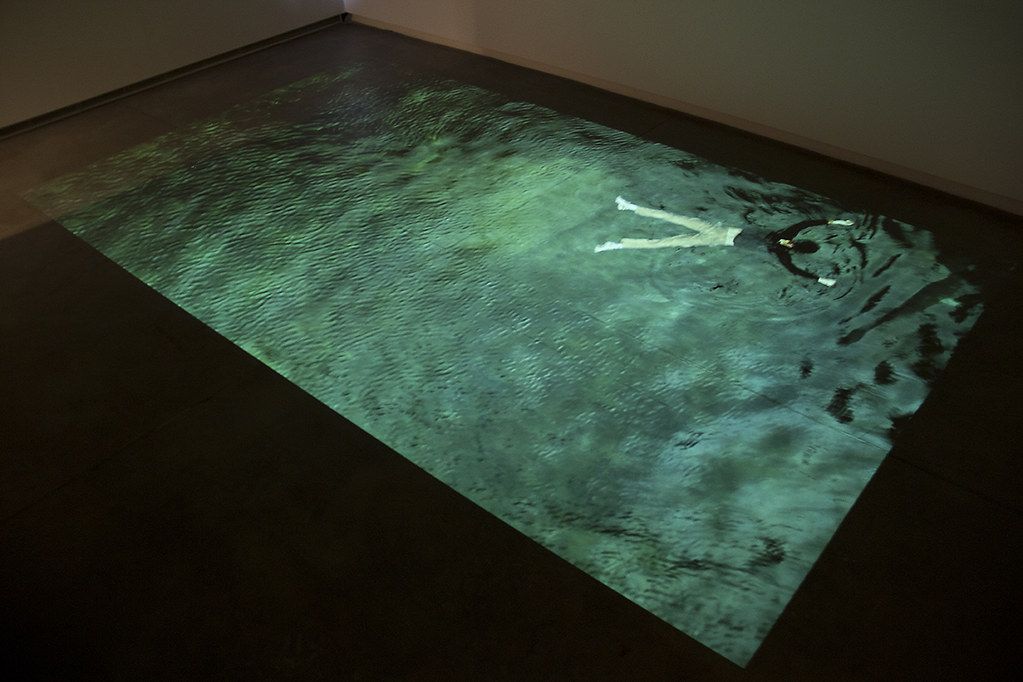

SALT has separated the exhibition Rabih Mroué literally and conceptually into two parts: The works at SALT Galata are mostly constructed around recounts from the artist’s life, while the works at SALT Beyoğlu are more recent, depicting mostly political demonstrations and social uprisings. Thus the SALT Galata work is concerned more with the distant Lebanese civil war whereas the works at SALT Beyoğlu have to do with representation of the (mostly Syrian) war. Coming from a theater background, Mroué’s work at SALT Galata constructs a narrative using detail from the artist’s biography.

Mroué, trained originally as a scriptwriter, actor and theater director, came to prominence along with a group of contemporary Lebanese artists who questioned the Lebanese civil war in terms of historicity, the writing of history, and the role of memory within that. Twenty-five years on, the effects of the 15-year-long war lurk around Beirut as strong as ever since the political situation never recovered from the deep fault lines formed during that period, be they political, religious or just bureaucratic. What Mroué’s generation of artists were concerned with was not merely their recounting of the war, but rather the representation of it. Other essential questions included what to do with the memories of war, whether it is better to forget or to remember them. All, important questions in a society defined by its political fault lines.

When I moved to Beirut at the end of 2009, a friend told me ‘Beirut is like a theater stage, it’s a mini-representation of all the conflicts that are happening in the region.’ Indeed Lebanon, with its mere four million of a population, and Beirut, with 1.5 million, contain all the politically symbolic conflicts of the region. This containment is well marked by the fact that governments become periodically stymied trying to negotiate between all the parties and interests present; case in point, there wasn’t a running government in place for the past 10 months up until February this year.

As much as the political landscape of Beirut is symbolic of the region, the daily experience of the city is quite far from that of Istanbul: The all too constant feeling of chaos in Beirut versus the ever-present struggle for the imposition of order in Istanbul. But as disparate as the feelings of these cities are, Mroué’s reflections on his war era life from his post-war self reverberate sound and loudly in this breaking moment of political tension in Istanbul. First as one thinks closely about the role of the intellectual in the political landscape, second with respect to the role theatricality plays on the political stage.

Post May 2013 has been a period of escalating political tensions in Turkey. The relationship between civil society demands and political responses has not been one of mutual consent. Rather, mutual destruction, accusations and confrontations fly high. Perhaps one of Erdoğan’s most successful methods has been his use of the body, his own body that is so performative and so grand that it creates a larger-than-itself cast, which is quite hard to shatter. This naturally blessed performativity he has cultivated over the years has been one of the strong components of political play which we have been witness to: The bodily, as well as the effects of the performative on the masses.

The work that sits off in a corner in the SALT Galata space, but is a core element of the exhibition conceptually, Rabih Mroué shows us three personalities in three acts: The Actor (in the original play) – The Resistance Fighter – The Politician. In On Three Posters: Reflections on a Video Performance by Rabih Mroue (video, 2004), the artist deciphers an earlier performance, which he had realized along with Elias Khoury some four years earlier. The original performance was about a video recording of a suicide bomber (The Resistance Fighter). The recording was found years later after the bomber’s death in the Communist Party’s headquarters. The video depicts the suicide bomber doing several takes for his suicide note, which would air on television as was customary during the war. We later watch two further acts by the Actor (the artist himself) and then by the Politician: The former contemplating on the format of the suicide note footage and the latter on the political context of this suicide.

The presentations by these three personalities bring up questions such as who has the right to talk about an act such as a suicide bomb, who has the right to summarize a history (the politician as an actor of the history, or the artist interpreting the politician by giving him an acting role in the video), and finally, of course, who can claim historical ownership of the past. The lecture-performance is overall wrapped up in constant self-critique, giving the work an almost confessional and repentant mode. The self-critique essentially states that the Lebanese left has failed. Not because it didn’t care enough, but because it failed to grasp fully the context of the war, confusing momentary ideological achievements for long term mobilization.

Three Posters analyzes the bodily and symbolic language performed by the suicide bomber as seen in the found footage. On Three Posters narrates the ways in which Three Posters made its rounds throughout Europe. During these rounds in Europe, the European media repeatedly chooses to communicate the play via the frame of the Lebanese civil war, and not necessarily in terms of the questions the artists want to pose: The author - actors (Khoury & Mroué) in Three Posters were concerned with the choice of the format of the suicide note and the meaning of this choice from a philosophical point of view about death: How does a suicide bomber think about their legacy and how does this translate to the potency of the moment right before death? Suleiman and Mroué were also concerned with the meaning of the choice from the perspective of the politician versus the artist: The politician’s reflections on the practical contextualization of the day versus the philosophical concerns of the artist. The European media, on the other hand, did not share these concerns and was merely concentrated on the fact that the artists were associated with the Lebanese intelligentsia. Mroue feels after the fact that the high popularity of Three Posters owed largely to a rather superficial interest in ‘war’ as a subject matter, and not necessarily an effort to grasp the internal conflicts of this specific war.

Turning the mirror on himself, Mroué’s essentially questions how the ‘left’ chooses to position itself, and whether it’s comfortable with the acting role it is assigned. Momentary fame should never be confused for long term commitment to historicity. On Three Posters is about the context specificity of a cultural work. As Mroué puts it, “our histories” only belong to us and can only be succinctly analyzed by those deeply familiar with those histories. But in actuality, it’s usually the more performative ones who get to stand on stage and tell these histories.

Mroué’s work distinguishes itself from the rest of the Lebanese artists’ from his generation: His works try not only to represent the war and the conflicts, but also negotiate Mroué’s (and his peers’) role within it. The irony of the works is strong because the autobiographical components are used as a means to distinguish and blur simultaneously between fact and fiction. In a country where there has not been a coherent history taught in schools past 1975, staging new histories has been a central element in the Lebanese artists’ works. When Mroué stages these histories, they are always self-histories, and in opposition to grand narratives, they ask the question: What was I doing at the time mentally, socially and what kind of responsibilities did I take on myself? Had I pursued other ‘conceptual’ paths, would the path of events have changed?

Local elections in Turkey on March 30 acted as the premier night culminating from months of rehearsals: Since the summer, the government had taken the local elections as a confidence vote on its policies, but more importantly on its way of governing. It has been commonly accepted that the three elections following one another (the local, the presidential and the general elections conducted within a year and half time frame) will be an endurance test for the current government to see if they can keep the social and public expectations in check. The methods most readily used in managing expectations have ranged from appealing to the emotional to censorship of certain media channels, as we have seen Twitter and YouTube banned within the last couple of months.

The Turkish political scene has been populated with various actors such as the opposition, the media, the civil society etc., and the intellectuals. The role of each of the other characters has been questioned, as too have the methods they call upon. But a critical breakdown of the role of the “Turkish left” is missing and is long overdue. In order to avoid asking the question, “Had I pursued other ‘conceptual’ paths, would the path of events have changed?” the Turkish left has to first study its recent history from the mid- century onwards, identify its current position and then stand firmly by that position.

*Zeynep Öz is an independent curator whose interest lies in the artistic production process.

SALT has separated the exhibition Rabih Mroué literally and conceptually into two parts: The works at SALT Galata are mostly constructed around recounts from the artist’s life, while the works at SALT Beyoğlu are more recent, depicting mostly political demonstrations and social uprisings. Thus the SALT Galata work is concerned more with the distant Lebanese civil war whereas the works at SALT Beyoğlu have to do with representation of the (mostly Syrian) war. Coming from a theater background, Mroué’s work at SALT Galata constructs a narrative using detail from the artist’s biography.

Mroué, trained originally as a scriptwriter, actor and theater director, came to prominence along with a group of contemporary Lebanese artists who questioned the Lebanese civil war in terms of historicity, the writing of history, and the role of memory within that. Twenty-five years on, the effects of the 15-year-long war lurk around Beirut as strong as ever since the political situation never recovered from the deep fault lines formed during that period, be they political, religious or just bureaucratic. What Mroué’s generation of artists were concerned with was not merely their recounting of the war, but rather the representation of it. Other essential questions included what to do with the memories of war, whether it is better to forget or to remember them. All, important questions in a society defined by its political fault lines.

When I moved to Beirut at the end of 2009, a friend told me ‘Beirut is like a theater stage, it’s a mini-representation of all the conflicts that are happening in the region.’ Indeed Lebanon, with its mere four million of a population, and Beirut, with 1.5 million, contain all the politically symbolic conflicts of the region. This containment is well marked by the fact that governments become periodically stymied trying to negotiate between all the parties and interests present; case in point, there wasn’t a running government in place for the past 10 months up until February this year.

As much as the political landscape of Beirut is symbolic of the region, the daily experience of the city is quite far from that of Istanbul: The all too constant feeling of chaos in Beirut versus the ever-present struggle for the imposition of order in Istanbul. But as disparate as the feelings of these cities are, Mroué’s reflections on his war era life from his post-war self reverberate sound and loudly in this breaking moment of political tension in Istanbul. First as one thinks closely about the role of the intellectual in the political landscape, second with respect to the role theatricality plays on the political stage.

Post May 2013 has been a period of escalating political tensions in Turkey. The relationship between civil society demands and political responses has not been one of mutual consent. Rather, mutual destruction, accusations and confrontations fly high. Perhaps one of Erdoğan’s most successful methods has been his use of the body, his own body that is so performative and so grand that it creates a larger-than-itself cast, which is quite hard to shatter. This naturally blessed performativity he has cultivated over the years has been one of the strong components of political play which we have been witness to: The bodily, as well as the effects of the performative on the masses.

The work that sits off in a corner in the SALT Galata space, but is a core element of the exhibition conceptually, Rabih Mroué shows us three personalities in three acts: The Actor (in the original play) – The Resistance Fighter – The Politician. In On Three Posters: Reflections on a Video Performance by Rabih Mroue (video, 2004), the artist deciphers an earlier performance, which he had realized along with Elias Khoury some four years earlier. The original performance was about a video recording of a suicide bomber (The Resistance Fighter). The recording was found years later after the bomber’s death in the Communist Party’s headquarters. The video depicts the suicide bomber doing several takes for his suicide note, which would air on television as was customary during the war. We later watch two further acts by the Actor (the artist himself) and then by the Politician: The former contemplating on the format of the suicide note footage and the latter on the political context of this suicide.

The presentations by these three personalities bring up questions such as who has the right to talk about an act such as a suicide bomb, who has the right to summarize a history (the politician as an actor of the history, or the artist interpreting the politician by giving him an acting role in the video), and finally, of course, who can claim historical ownership of the past. The lecture-performance is overall wrapped up in constant self-critique, giving the work an almost confessional and repentant mode. The self-critique essentially states that the Lebanese left has failed. Not because it didn’t care enough, but because it failed to grasp fully the context of the war, confusing momentary ideological achievements for long term mobilization.

Three Posters analyzes the bodily and symbolic language performed by the suicide bomber as seen in the found footage. On Three Posters narrates the ways in which Three Posters made its rounds throughout Europe. During these rounds in Europe, the European media repeatedly chooses to communicate the play via the frame of the Lebanese civil war, and not necessarily in terms of the questions the artists want to pose: The author - actors (Khoury & Mroué) in Three Posters were concerned with the choice of the format of the suicide note and the meaning of this choice from a philosophical point of view about death: How does a suicide bomber think about their legacy and how does this translate to the potency of the moment right before death? Suleiman and Mroué were also concerned with the meaning of the choice from the perspective of the politician versus the artist: The politician’s reflections on the practical contextualization of the day versus the philosophical concerns of the artist. The European media, on the other hand, did not share these concerns and was merely concentrated on the fact that the artists were associated with the Lebanese intelligentsia. Mroue feels after the fact that the high popularity of Three Posters owed largely to a rather superficial interest in ‘war’ as a subject matter, and not necessarily an effort to grasp the internal conflicts of this specific war.

Turning the mirror on himself, Mroué’s essentially questions how the ‘left’ chooses to position itself, and whether it’s comfortable with the acting role it is assigned. Momentary fame should never be confused for long term commitment to historicity. On Three Posters is about the context specificity of a cultural work. As Mroué puts it, “our histories” only belong to us and can only be succinctly analyzed by those deeply familiar with those histories. But in actuality, it’s usually the more performative ones who get to stand on stage and tell these histories.

Mroué’s work distinguishes itself from the rest of the Lebanese artists’ from his generation: His works try not only to represent the war and the conflicts, but also negotiate Mroué’s (and his peers’) role within it. The irony of the works is strong because the autobiographical components are used as a means to distinguish and blur simultaneously between fact and fiction. In a country where there has not been a coherent history taught in schools past 1975, staging new histories has been a central element in the Lebanese artists’ works. When Mroué stages these histories, they are always self-histories, and in opposition to grand narratives, they ask the question: What was I doing at the time mentally, socially and what kind of responsibilities did I take on myself? Had I pursued other ‘conceptual’ paths, would the path of events have changed?

Local elections in Turkey on March 30 acted as the premier night culminating from months of rehearsals: Since the summer, the government had taken the local elections as a confidence vote on its policies, but more importantly on its way of governing. It has been commonly accepted that the three elections following one another (the local, the presidential and the general elections conducted within a year and half time frame) will be an endurance test for the current government to see if they can keep the social and public expectations in check. The methods most readily used in managing expectations have ranged from appealing to the emotional to censorship of certain media channels, as we have seen Twitter and YouTube banned within the last couple of months.

The Turkish political scene has been populated with various actors such as the opposition, the media, the civil society etc., and the intellectuals. The role of each of the other characters has been questioned, as too have the methods they call upon. But a critical breakdown of the role of the “Turkish left” is missing and is long overdue. In order to avoid asking the question, “Had I pursued other ‘conceptual’ paths, would the path of events have changed?” the Turkish left has to first study its recent history from the mid- century onwards, identify its current position and then stand firmly by that position.

*Zeynep Öz is an independent curator whose interest lies in the artistic production process.