To the Spirit of Assos at Lake Bafa

Nadi Güler

January 20, 2023

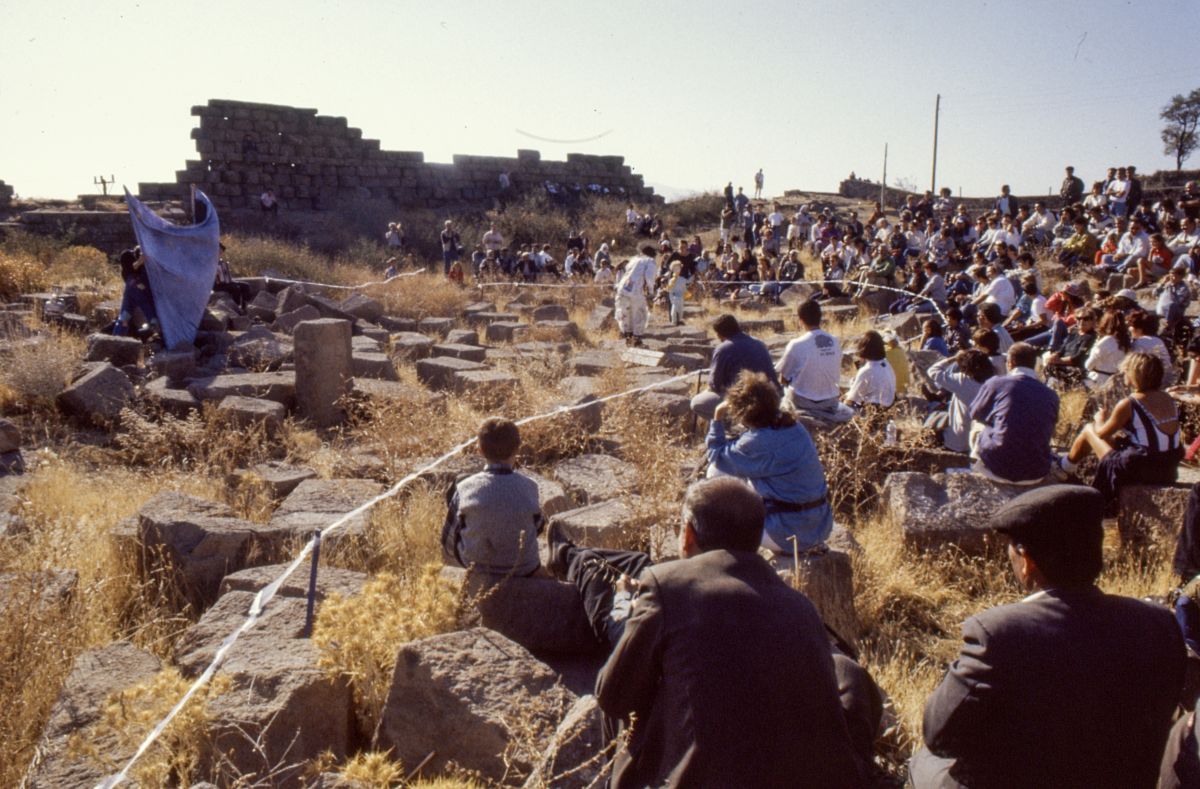

L’Outil, Yolda I-II-III [On The Road I-II-III], 1995

Photo: Levent Öget

Photo: Levent Öget

At the beginning of the 1990s, when we were not well familiar with the timely consequences occurring around the world, a collective movement within the field of contemporary performing arts had emerged in Assos, thanks to the efforts of Hüseyin Katırcıoğlu. After many years of working in acting and directing in the United Kingdom and the United States, Katırcıoğlu returned to Turkey and produced similar works. Even those who didn’t know him could tell that his efforts were to bring significant results when they read his interviews in the newspapers. As a matter of fact, in 1992, at the International Theatre Institute’s meeting held in Turkey, several important foreign theater actors conducted workshops. Ellen Stewart’s work on Yunus Emre was among these, which was later performed at Hagia Irene and brought to Stewart’s famous theater La MaMa E.T.C. (Experimental Theatre Club) in New York. The show was presented to the American audience in a two-week program following a month-long rehearsal period, and the cast comprised Ayla and Beklan Algan, Erol Keskin, Hüseyin Katırcıoğlu, Mustafa Avkıran, Levent Güner, Kaan Erten, Zişan Uğurlu, Aslı Öngören, and Nadi Güler alongside international actors. After getting critically acclaimed by the Village Voice and New York Times as “the most beautiful oriental tale since Scheherazade”, the cast of this sold-out play performed another show, Truva Öyküsü [A Trojan Story], in the ancient city of Troy in Çanakkale the following year. Hüseyin Katırcıoğlu had a house in Behramkale, Assos since many years. After this production came to an end, he initiated the Assos Performing Arts Festival.

Assos became part of the lexicon of contemporary performing arts when Hüseyin, with such international experience, bought a house in Behramkale twenty years ago. Assos Performing Arts Festival was made possible with collective efforts that provided material and accommodation support, mostly covered by out-of-pocket expenses. The institutional development progressed in time, and several significant productions were undertaken as part of the festival, where Turkish and foreign artists worked together.

As a method, the festival operated on the principle of producing a program following several weeks of rehearsals, upon the participation of various theater and contemporary dance companies invited to Assos annually. Eventually, it became an international organization in which the invited groups presented their shows in selected venues. These site-specific projects were open to communication and collaboration with other working groups, and even the village youth took part in the shows as actors.

Women from the village sewed the costumes in their homes, others made lunch, and props were produced in the elementary school while actors were rehearsing in the selected venues. The elderly from the village would correct the performers according to the traditional folk dance Harmandalı. Japanese musicians with Yamaha keyboards would have a hard time catching the off-beat rhythm of the original score while finger-counting the notes and complaining about the impossibility of pulling it off. The production van would go back and forth between sites to solve the practical issues. When it was finally time to call it a day with the rehearsals, we would visit the livestock to feed them with Süreyya, one of our helping hands from the village. In the evenings, we would join feasts or weddings in the village, dance Harmandalı with the youngsters of Behramkale, dine and drink rakı at the table saved for us.

Countless memories come to mind from this period spanning over six years: Aydın Teker working on her project with a shepherd and herd of sheep on the old arched bridge at the entrance of the village, Mustafa Kaplan trying to find his balance with an Indian dancer on a litter placed on a big boat, theater company Kumpanya making yet another version of Everest My Lord in an abandoned cabin on the hill afar from the residential area, Sabine Jamet having her take on The Little Prince with puppets alongside children from the village, Zeynep Günsür relentlessly carrying her newborn child to each and every show, Beklan Algan rehearsing a scene from Iliad on the cliffs of Troy sacrificing his daughter Iphigenia to the deities with a giant sword in his hand, Erol Kesin roaring at the audience, “Behold!”. Yet, Assos Performing Arts Festival came to an end prematurely when Hüseyin Katırcıoğlu passed away because of an unfortunate accident.

Engaging with similar summer activities organized by Ellen Stewart in Spoleto, Italy, Katırcıoğlu sought a model that would convey his creativity to other platforms. This could be considered as a process of purification by nature outside the city, as seen in other cases like [Jerzy] Grotowski working in the mountains in his last years or Eugenio Barba settling in a small town to continue his work.

In a sense, just as chaos and cacophony of urban settings meet the needs of certain artistic practices to activate creativity, the serenity of nature responded to the ingrowing tendencies of art that paralleled Eastern teachings.

This experience constituted an unprecedented model for site-specific performance that brought art and nature together. It was a radical proposition for the local contemporary theater and dance community stuck around Taksim area in Istanbul. With a range of installations and performances, the festival established a social setting between Istanbul and Assos which led some works to be reiterated in Istanbul.

Decades passed by, and some of the participating artists went on to produce works similar to the Assos experience—this time in the ancient city of Heraclea, the place of the moon goddess Selene, located at the foothill of Mount Latmos around Lake Bafa in Muğla. The principle was still the same: to enrich one’s own language through the abundance of nature, to get a little closer to the village and the naivety of the peasant.

Nature can be so instructive in such situations that, as told in a famous fable, even an encounter with a tiny ant would suffice to make us feel self-conscious because of acting like “grasshoppers”.

Over the years, the works of Çatı Contemporary Dance Artists’ Association and Avrasya Art Collective Association in Istanbul resulted in climbing and camping trips based on a series of workshops, children’s projects, and site-specific presentations. Without any doubt, the spiritual investment across the region will turn into new experiences through the affordances provided by a new settlement in Garanbuaz near Kapıkırı Village.

The energy released from the valley in Garanbuaz, an arduous area with steep rocks, rises together with the sacred mountain of Latmos, as if it was evoking the spirit of Assos.

*This text, first issued on the semi-annual contemporary performing arts magazine gist (no: 2, July-December 2008, pp. 30-31), is translated by Sarp Özer and Ezgi Yurteri, and republished as part of the exhibition The 90s Onstage.

Assos became part of the lexicon of contemporary performing arts when Hüseyin, with such international experience, bought a house in Behramkale twenty years ago. Assos Performing Arts Festival was made possible with collective efforts that provided material and accommodation support, mostly covered by out-of-pocket expenses. The institutional development progressed in time, and several significant productions were undertaken as part of the festival, where Turkish and foreign artists worked together.

As a method, the festival operated on the principle of producing a program following several weeks of rehearsals, upon the participation of various theater and contemporary dance companies invited to Assos annually. Eventually, it became an international organization in which the invited groups presented their shows in selected venues. These site-specific projects were open to communication and collaboration with other working groups, and even the village youth took part in the shows as actors.

Women from the village sewed the costumes in their homes, others made lunch, and props were produced in the elementary school while actors were rehearsing in the selected venues. The elderly from the village would correct the performers according to the traditional folk dance Harmandalı. Japanese musicians with Yamaha keyboards would have a hard time catching the off-beat rhythm of the original score while finger-counting the notes and complaining about the impossibility of pulling it off. The production van would go back and forth between sites to solve the practical issues. When it was finally time to call it a day with the rehearsals, we would visit the livestock to feed them with Süreyya, one of our helping hands from the village. In the evenings, we would join feasts or weddings in the village, dance Harmandalı with the youngsters of Behramkale, dine and drink rakı at the table saved for us.

Countless memories come to mind from this period spanning over six years: Aydın Teker working on her project with a shepherd and herd of sheep on the old arched bridge at the entrance of the village, Mustafa Kaplan trying to find his balance with an Indian dancer on a litter placed on a big boat, theater company Kumpanya making yet another version of Everest My Lord in an abandoned cabin on the hill afar from the residential area, Sabine Jamet having her take on The Little Prince with puppets alongside children from the village, Zeynep Günsür relentlessly carrying her newborn child to each and every show, Beklan Algan rehearsing a scene from Iliad on the cliffs of Troy sacrificing his daughter Iphigenia to the deities with a giant sword in his hand, Erol Kesin roaring at the audience, “Behold!”. Yet, Assos Performing Arts Festival came to an end prematurely when Hüseyin Katırcıoğlu passed away because of an unfortunate accident.

Engaging with similar summer activities organized by Ellen Stewart in Spoleto, Italy, Katırcıoğlu sought a model that would convey his creativity to other platforms. This could be considered as a process of purification by nature outside the city, as seen in other cases like [Jerzy] Grotowski working in the mountains in his last years or Eugenio Barba settling in a small town to continue his work.

In a sense, just as chaos and cacophony of urban settings meet the needs of certain artistic practices to activate creativity, the serenity of nature responded to the ingrowing tendencies of art that paralleled Eastern teachings.

This experience constituted an unprecedented model for site-specific performance that brought art and nature together. It was a radical proposition for the local contemporary theater and dance community stuck around Taksim area in Istanbul. With a range of installations and performances, the festival established a social setting between Istanbul and Assos which led some works to be reiterated in Istanbul.

Decades passed by, and some of the participating artists went on to produce works similar to the Assos experience—this time in the ancient city of Heraclea, the place of the moon goddess Selene, located at the foothill of Mount Latmos around Lake Bafa in Muğla. The principle was still the same: to enrich one’s own language through the abundance of nature, to get a little closer to the village and the naivety of the peasant.

Nature can be so instructive in such situations that, as told in a famous fable, even an encounter with a tiny ant would suffice to make us feel self-conscious because of acting like “grasshoppers”.

Over the years, the works of Çatı Contemporary Dance Artists’ Association and Avrasya Art Collective Association in Istanbul resulted in climbing and camping trips based on a series of workshops, children’s projects, and site-specific presentations. Without any doubt, the spiritual investment across the region will turn into new experiences through the affordances provided by a new settlement in Garanbuaz near Kapıkırı Village.

The energy released from the valley in Garanbuaz, an arduous area with steep rocks, rises together with the sacred mountain of Latmos, as if it was evoking the spirit of Assos.

*This text, first issued on the semi-annual contemporary performing arts magazine gist (no: 2, July-December 2008, pp. 30-31), is translated by Sarp Özer and Ezgi Yurteri, and republished as part of the exhibition The 90s Onstage.