Notes on Air

Erica Petrillo (2050+)

August 11, 2024

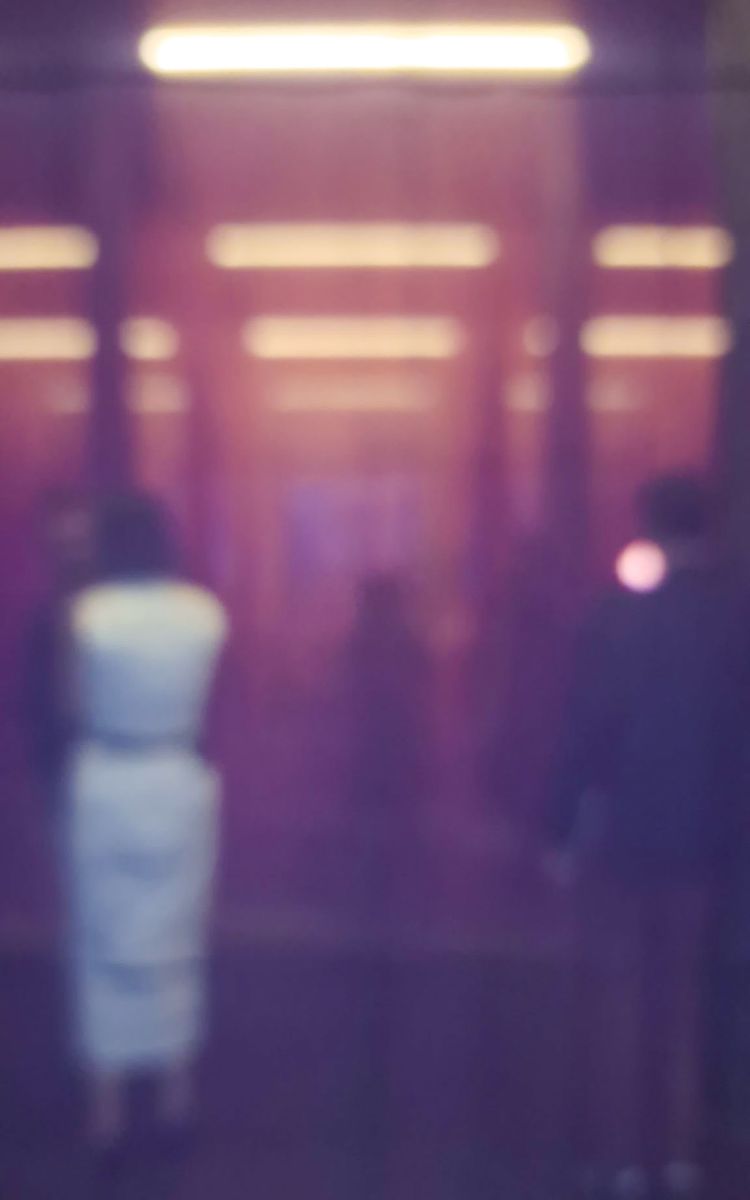

Installation view from Notes on Air, Salt Beyoğlu, 2024

Photo: Mustafa Hazneci (Salt)

Photo: Mustafa Hazneci (Salt)

Erica Petrillo from the Milan-based interdisciplinary agency 2050+ elaborates on their immersive installation and research project, “Notes on Air,” on view at Salt Beyoğlu until August 18.

Is not air the whole of our habitation as mortals? Is there a dwelling more vast, more spacious, or even more generally peaceful than that of air? Can man live elsewhere than in air? […] No other element is as light, as free, and as much in the “fundamental” mode of a permanent, available, “there is.”1

In her book L’oubli de l’air chez Martin Heidegger [The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger] (1983), Belgian-born feminist philosopher, psychoanalyst, and cultural theorist Luce Irigaray engages with the later work of the eminent German philosopher, critiquing Heidegger’s emphasis on the element of earth as the ground of life and speech and his “oblivion” or forgetting of air. The centrality of the earth in Western history of thought, which Irigaray detects in Heidegger’s philosophy, is something we all have experienced. Think, for instance, about the linguistic expressions we use every day to affirm—perhaps inadvertently and yet effectively—the “supremacy” of the earth over other elements, and what appears to be its instrumental role in the development of human civilization. When we think of Western history, which is a history of nation-states, we think of the export (or, more often, the violent imposition) of a political structure characterized by military and bureaucratic control over patches of land. And the characters of such a history, that is to say, those who inhabit these patches of land, swear allegiance (and sometimes kill or die) in the name of that abstract concept, which is the Motherland or the Fatherland.

And yet, Luce Irigaray argues, behind a philosophy that never leaves the ground—”whether it be that of the earth or that of logos”2—there is something amiss. Heidegger, and with him Western philosophy, have indeed forgotten to think of air, and by doing so, think of the medium in which all worldly things exist. Has the philosopher forgotten to take a breath?—she asks herself. In her words: “Air would be the substance of the copula that would permit the gathering-together [le rassemblement] and the arrangement of the whole into the life and Being of man, and permit his habitation in space as a mortal.”3 In the same book, she also wonders whether the air is feminine, since it gives every living being subsistence, and because it is unrepresentable and fluid—not rigid, like the earth, Heidegger, and Western philosophy.

These ideas—the repositioning of air and the re-reading of a basic principle in Western metaphysics—were key for the conceptualization of Notes on Air at Salt Beyoğlu, an immersive installation and research project conceived and designed by the interdisciplinary agency 2050+.

Notes on Air strives to recenter air by giving presence to an element that otherwise “doesn’t show itself”, “escapes appearing as a being”, and thus “allows itself to be forgotten”4—what is out of sight can very easily fall out of mind. For us at 2050+, an agency of architects, designers, and curators, the research process behind the installation began with a series of pivotal notes on air borrowed from the worlds of environmental studies, spatial practices, and philosophy, challenging the idea of air as a void or an absence. Here are some of these tenets:

Air is a space. More precisely, the thin layer of air we inhabit is the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere (it contains 75% of its total mass), in direct contact with the Earth’s surface. This layer, which varies in thickness between 8 and 14 km depending on time and location, is where most weather phenomena occur.

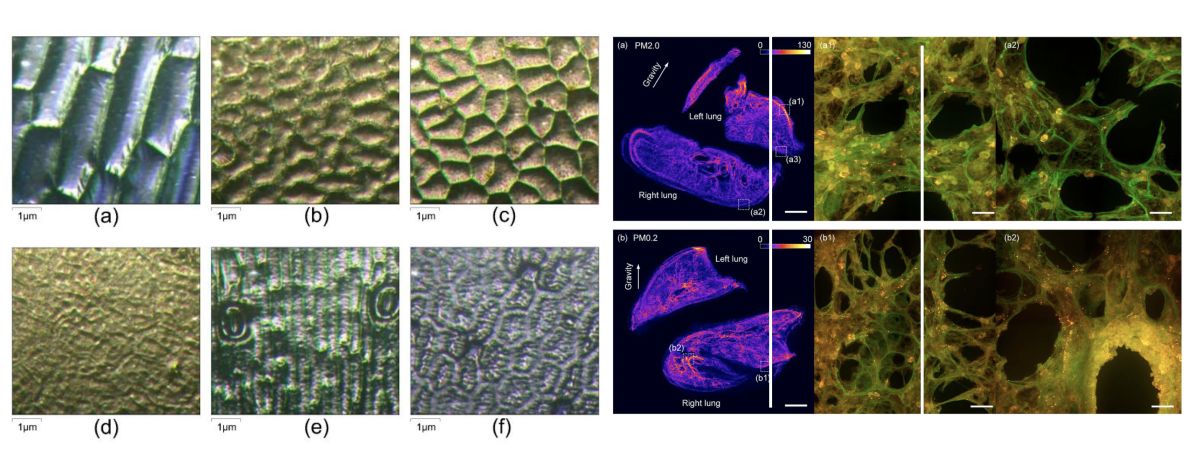

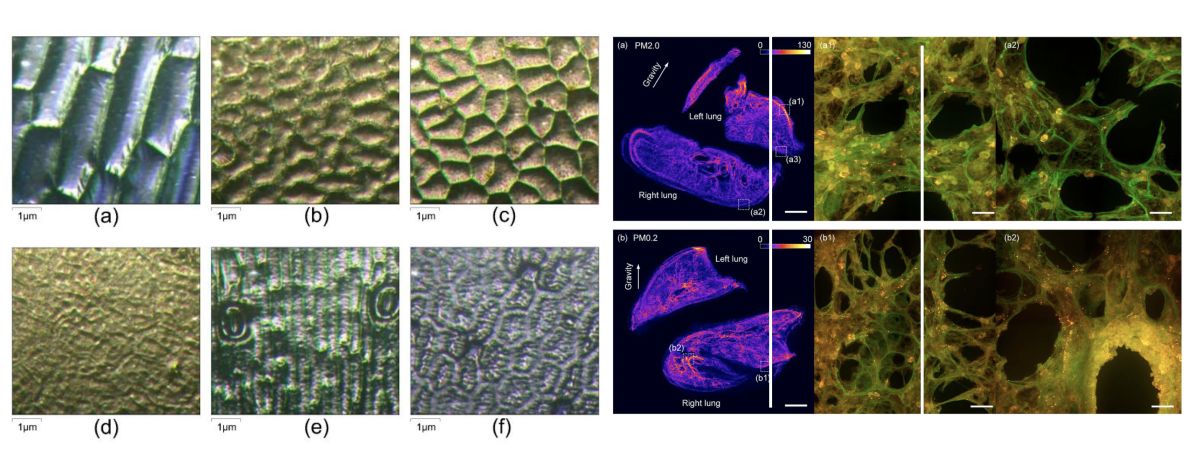

Air has materiality. It is laden with particles that, despite evading the human eye, remain a constant presence in our lives. These particles create a fundamental condition for existence (breathing is living), while also harboring the potential for lethality. This is especially true for particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) and 10 (PM10)—pollutants with diameters of 2.5 and 10 micrometers, respectively (for scale, consider that the diameter of the average human hair would be 30 times larger than PM2.5). The size of these particles makes them especially hazardous, as they can reach the bronchi, the trachea, the upper respiratory tract, and even the bloodstream.

Air toxicity is a product of the Anthropocene, and it affects humans and other-than-humans alike: animals of course (humans included), but also plants and natural environments at large, thus turning toxicity into a condition that “connects environmental vulnerability with spatial and social factors.”5

Air (and air toxicity) is transcalar. This makes it impossible to observe air from a fixed point of view or at a fixed scale—air is an element that is both microscopic and macroscopic, and its reach extends from local to planetary.

Air (and air toxicity) is transborder. The “floating bodies”6 suspended in the air move according to a complicated transport system that follows the mechanics of the climate and is indifferent to human-made borders. From this, it follows that the effects of pollution are redistributed according to a meteorological process rather than a geopolitical one, where “the space of violation is separated from the space of its repercussion.”7 Those least responsible for emissions might be (and often are) most susceptible to its destructive effects, while those most responsible may remain (and often do) unaccountable and unpunished. As architect and researcher Adrian Lahoud has put it, “The earth’s climate loosens the bond between cause and effect; it breaks the link between attribution, responsibility, and, potentially, justice.”8

Air is a common. It is a shared domain where the actions of one region reverberate across vast distances, and by virtue of its communality, collective actions are imperative to ensure that clean and breathable air is a universal right for both present and future generations.

Finally, air (and air toxicity) calls for forms of environmental attuned sensing— strategies for detecting that expand the ways in which air can be perceived beyond quantitative data and the realm of science. Unclean air can be studied and monitored through quantifiable data and scientific tools that “make it visible” (i.e., detectable and observable). Yet, “vision is not the only way of knowing.”9 As feminist architect and scholar Nerea Calvillo argues:

“Science accounts for this accumulation [of the infrastructures, devices, practices, and bodies that make up the air] through numbers and concentrations, but this account only provides for one condition of pollution, as well as suggesting technoscientific stories as ‘solutions’ concerned with cleaning it through massive geoengineering projects. In a similar manner to climate change, numbers become too abstract and detached from reality for people to engage with them in meaningful ways.”10

To bridge the gap between understanding and acting, Calvillo argues, it is necessary to challenge “what counts as evidence in toxic regimes”11 and expand our “regime of perceptibility”12 to practices that are sensorial, situated, and embodied, as well as cognitive and visual.

With these powerful considerations in mind, the challenge we set for ourselves with Notes on Air was to conceive a project that could account for all these intricate layers. We worked towards an installation that embraces the multiplicity of ways in which air and air toxicity can be conceptualized, endured, and dealt with. Through this aesthetic and artistic exploration, we sought to give presence to an element that is typically invisible, intangible, and inaudible. Our approach involved a blend of visual, haptic, and sonic experiments, presenting air as both a scientific and a social, philosophical, and affective condition.

The installation is articulated through three components:

An immersive soundscape that envelops the entire exhibition space, inviting listeners to engage with the materiality of the “air-scape.” Commissioned by 2050+ and created by sound artist Francesco D’Abbraccio (aka Lorem), the piece isolates and aesthetically translates various layers of atmospheric information and entities (such as radio waves, electromagnetic currents, living noises, particulate matter, and other forms of information) into sonic experiences. It captures the traces of colliding bodies, small impacts, frictions, and rustling sounds.

The intuition that the aerial landscape is a buzzing ecology of particles that are not only invisible to the human eye but also inaudible came into the conversation with eco-toxicologist Prof. Dr. Melek Türker Saçan (Boğaziçi University). She suggested that if we could hear the crackling noises generated by the countless chemical reactions triggered by pollutants in the air, we would be much warier of their presence and, thereby, their effect. The truism that “seeing is believing” here is given a sonic resignification.

Central to Francesco D’Abbraccio’s conceptualization was an immersive soundscape to be traversed and explored, which he executed through a 14-channel sound system. This audio technique was designed to transmit sound across various speakers throughout the exhibition space, enveloping the listener in a dynamic auditory experience. Each channel represents distinct atmospheric phenomena. The physical movement of the audience through the exhibition space becomes a mode for exploring the unseen layers of the environment, transforming the listener into an active participant in discovering air as a sonic battlefield, rather than an empty and silent void.

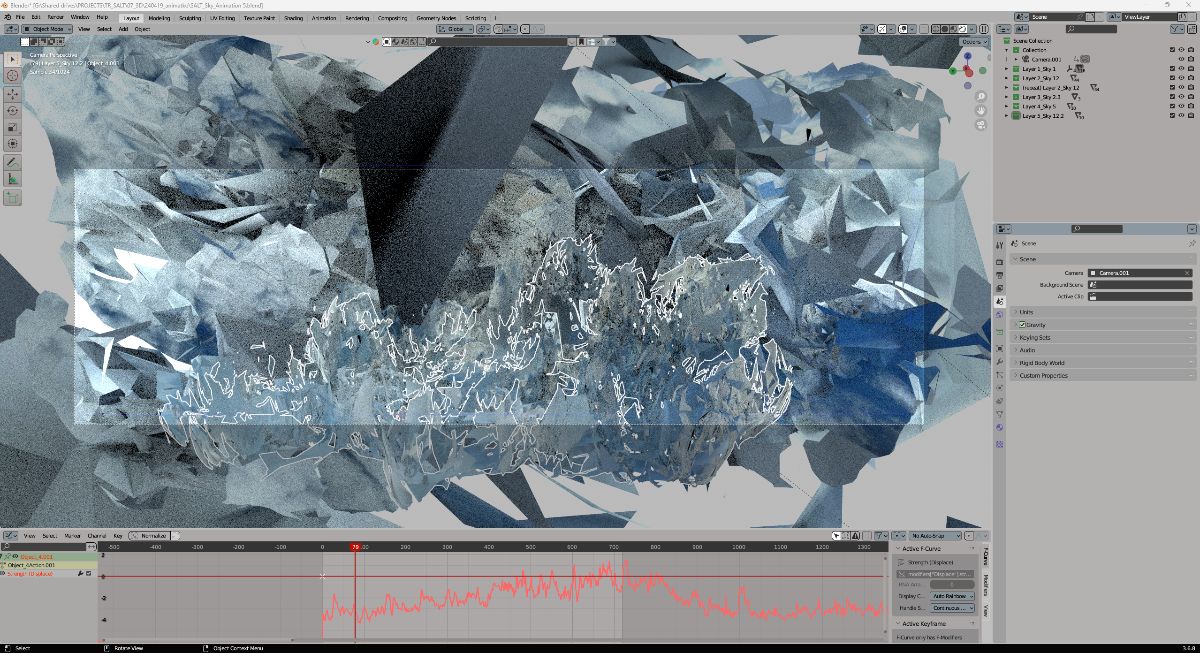

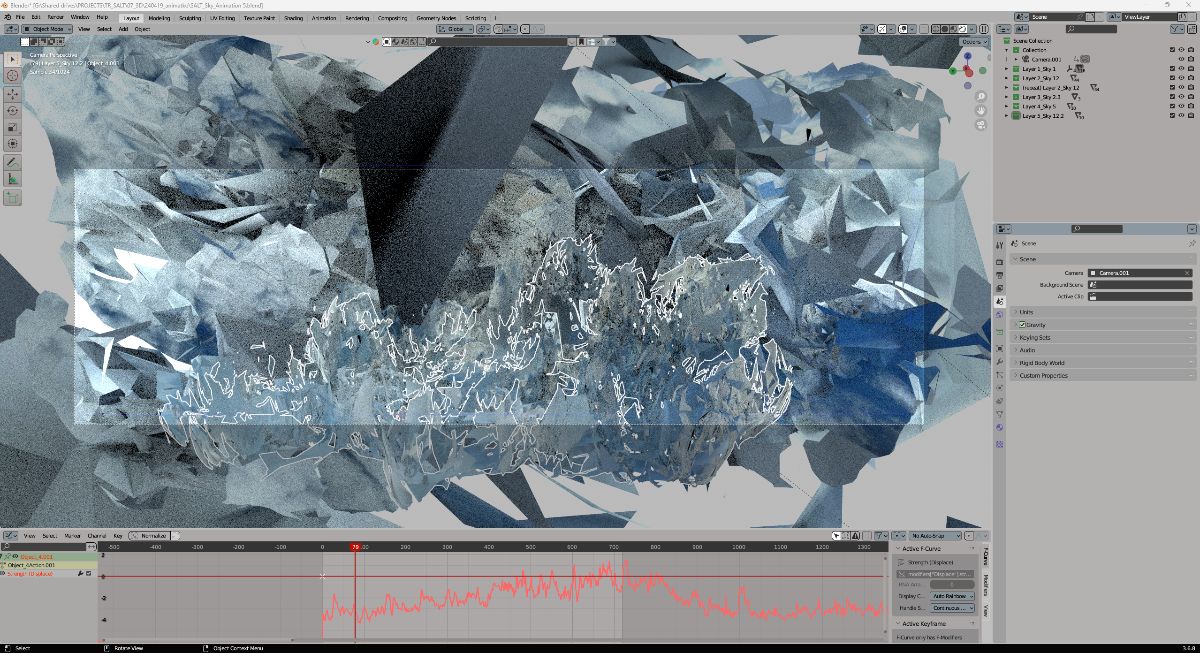

A digital reconstruction of the air-scape in Istanbul, displayed on a screen situated at the far end of the exhibition space, spanning seven meters in width and elevated slightly above eye level. The animation was produced by 2050+ using photogrammetry software, a tool that employs photographic material to survey and map physical environments, measure distances between objects, and ultimately reconstruct them. While photogrammetry is primarily used for physical, solid, and static elements of our built environment, we applied it to evidence and give form to a moving, elusive, gaseous substance: a mass of condensed water vapor in flux. In this way, we could draw attention to the flaws and limits of a science and technology that excel in recording, measuring, and interpreting a specific type of imagery, but whose reliability cracks when used outside its intended scope. Such limits became the basis for an artistic reinterpretation. The result appears as a jagged, spiky digital landscape, functioning almost as a visual counterpoint to the soundscape of Francesco d’Abbraccio. The glitches and vibrations on the screen resonate with the hisses and crackles of the sonic piece, offering two imagined reinterpretations of the air’s invisibility.

The last and perhaps most pertinent element of the installation is a series of hanging fabrics that rhythmically punctuate the Salt Beyoğlu space, as if dividing the space into sections. These fabrics, suspended from the ceiling, are subtly swayed by the airflow from Istiklal Street, directly connecting the exhibition space with a portion of public space.

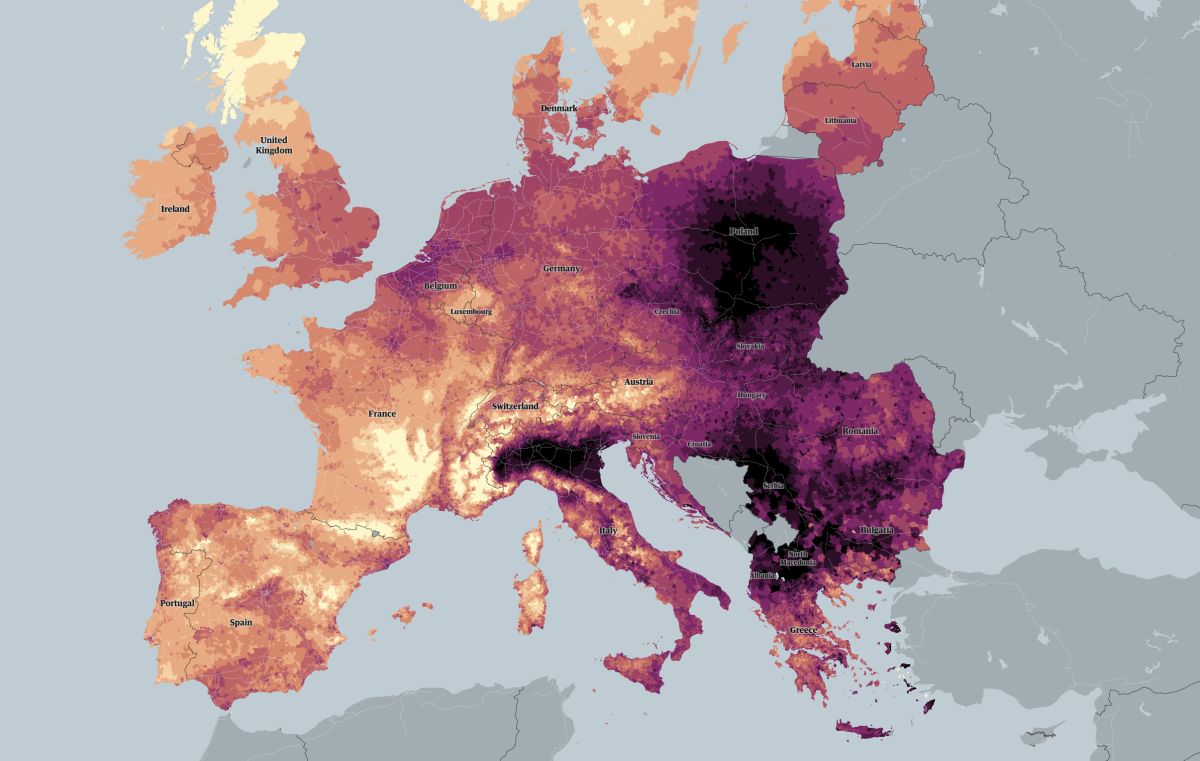

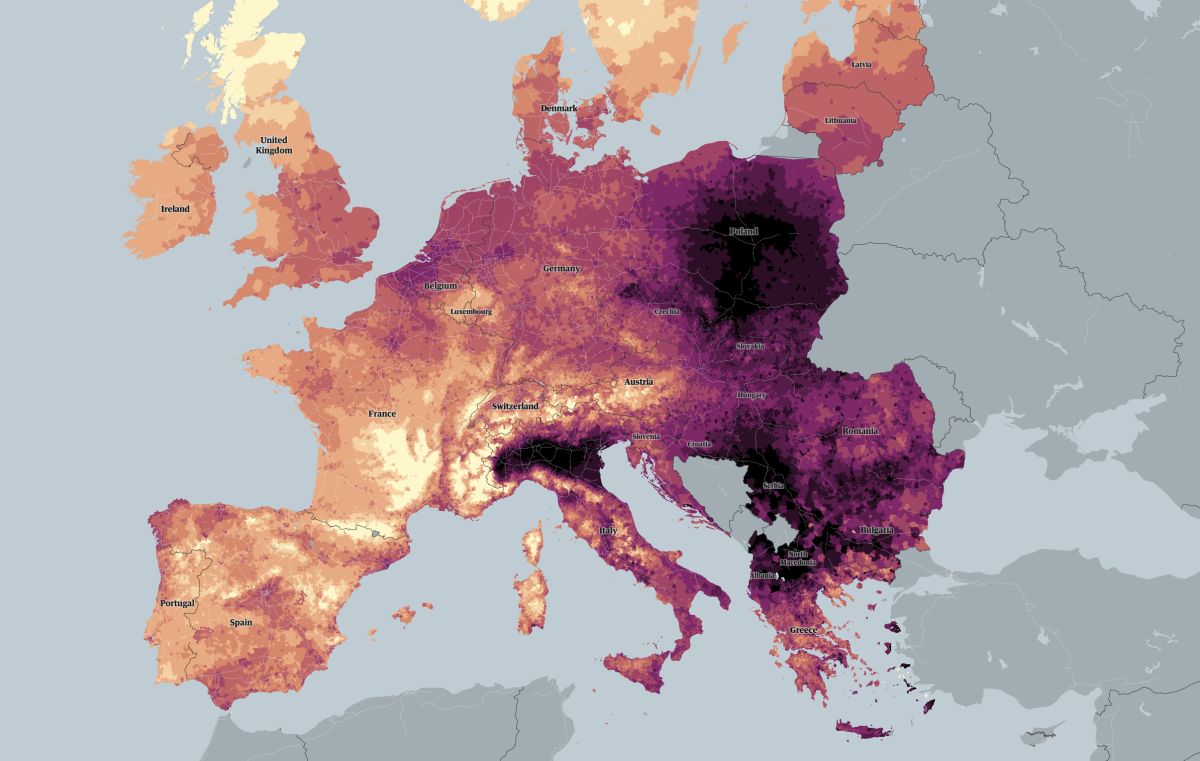

The materiality of the hanging fabrics is accentuated by their colors. Each layer is dyed with a unique hue, corresponding to differing levels of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air (estimate based on 2019 averages). This spectrum, ranging from light yellow (indicating almost zero micrograms) to deep purple (a concentration of 19 micrograms and above), is frequently employed to illustrate PM2.5 particle concentration in the atmosphere.

Maps such as those published by The Guardian in 2023 have the advantage of condensing complex scientific data (i.e., the concentration of micro-pollutants in the air) into a form that is readable and emotionally impactful (via a color gradient). The issue of “data literacy” (i.e., the ability to read and interpret the language of data) is central here. A telling example is the color purple, which represents the highest degree of particle concentration in the air (i.e., the most toxic) and that only in recent years has been included in the spectrum of the color-coded air quality index, replacing the color red. According to data visualization designer Giorgia Lupi, purple is a color that evokes a sense of unsettling lividity: “Think of bruises, and the color purple on skin when talking about disease. It is another level. It’s darker, and a more advanced stage [than red], if you will.”13 Red is indeed “the color of alert, of stop signs,”14 but in the era of climate catastrophe, even red is not enough.

Color gradient scheme (Courtesy 2050+)

Color gradient scheme (Courtesy 2050+)

On the other hand, despite their immediacy, these types of maps fail to provide a granular understanding of air toxicity. They flatten out any kind of social and cultural specificity, allowing only the human convention of political borders to emerge. Playing once again with the notion of limits and flaws (this time not through photogrammetry as a tool, but through cartography as a representational medium), we decided to adopt this conventional way of visualizing air toxicity based on color coding and give it tactile presence through the hanging fabrics at Salt Beyoğlu.

Detail of the graphics embroidered on the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

Detail of the graphics embroidered on the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

In addition, each layer of hanging fabric depicts a key pollutant that is notably harmful and widespread in Istanbul’s air: nitrogen dioxide, ozone, carbon dioxide, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide. Functioning as fluctuating boards, the hanging curtains overlay three types of data: the concentration of each pollutant in Istanbul over the course of one year (2020-2021); the anthropogenic sources responsible for the high concentration of that pollutant (construction, ore extraction, industrial activities, burning fossil fuels, etc.); and the effects of that air pollutant on human and non-human health (asthma, fatigue, reduced oxygen in the blood, dizziness, etc.). Crucially, these layers of scientific information, which rely on numbers, hard data, and quantitative analysis, are represented on the hanging fabrics through embroidery—a technique traditionally associated with domesticity, female artisanship, warmth, and intimacy. Not only is the intangible condition of air toxicity given haptic presence, but also the language of science used to describe it is softened, rendered tactile and more accessible.

Detail of the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

Detail of the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

The idea of weaving stories of air toxicity onto the fabrics was inspired by Sardinian artist Maria Lai, best known for her textile works and described by critic Giorgio Di Genova as a “poetic amanuensis of sewing.” Reclaiming ancient Sardinian traditions with sensitivity and talent, Maria Lai gave artistic depth to a practice traditionally associated with the ordinary and domestic, and transformed embroidery into a tool of personal expression and emancipation. In her famous textile diaries, her thoughts and impressions are inscribed with a thread and needle: some words can be deciphered on the fabric pages, but most remain unreadable. Similarly, the embroidered data in the exhibition can only be partly interpreted: the size of the hanging fabrics makes it difficult to read them all at once, and visitors have to content themselves with the sense that they have grasped an impression. It is precisely within this space of suspension—where rational understanding needs to halt and techno-scientific tools fall short—that we found a fitting metaphor for our approach to air and air toxicity: suspension as a method.

With these three interrelated components (the sonic, the visual, and the haptic), Notes on Air wishes to introduce novel methodological, conceptual, and discursive frameworks for contemplating issues around air and air toxicity. Crucially, it does so within the context of a cultural institution—thereby fulfilling the responsibility of contemporary art spaces as forums for interdisciplinary discussion. In this sense, Notes on Air is not only an installation but also a call to responsibility—for visitors and cultural institutions alike—and an exploration of how the languages of art, science, and activism converge within such a forum.

Ultimately, Notes on Air is a hymn to the potential for generating new interpretations of the world. Much like Luce Irigaray in L’oubli de l’air, and many other scholars, artists, and anonymous citizens who have sought to bring to the fore novel protagonists and questioned dominant narratives (be it the hegemony of the earth over other elements or of certain forms of artistic expression over embroidery), Notes on Air presents a similar challenge: interrogating the status quo to weave alternative interpretations of reality—a necessary premise for any attempt to change it. This is now more vital than ever, both within and beyond the realm of cultural institutions.

- - -

Exhibition conceived and designed by 2050+ (Che Facchin, Guglielmo Campeggi, Erica Petrillo, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, Kamil Dalkir, Meera Badran, Nils Grootenzerink, Sara Barbini)

Sound Designer: Francesco D’Abbraccio aka Lorem

Production: Emirhan Altuner

Salt project team: Eylül Şenses, Emirhan Altuner, Fatma Çolakoğlu

Advisor: Prof. Dr. Melek Türker Saçan (Boğaziçi University)

2050+ is an interdisciplinary agency based in Milan whose work revolves around diverse forms of critical spatial practices at the intersection of technology, politics, and the environment. Founded in 2020, 2050+ has carried out a range of projects spanning curatorial and research practices, exhibition design, and architecture. 2050+ regularly collaborates with various institutions to create temporary installations, films, public events, and editorial initiatives. The agency is also committed to independent research projects, including short films and critical texts featured on numerous publishing platforms. These projects often address the relationship between data and the material world—a line of research that 2050+ explores in the context of ADS8: Data Matter, a research and design studio at the Royal College of Art in London.

Erica Petrillo is a curator and researcher with a background in political philosophy and social sciences. She collaborates with the interdisciplinary agency 2050+ and works on several independent projects in parallel. She has curated public programs and exhibitions for various cultural institutions in Italy and abroad. Before joining 2050+, she worked at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where she was responsible for the series of monthly R&D Salons; co-curated Broken Nature, the XXII Triennale di Milano in 2019; and was the 2019-2020 curator-in-residence at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht.

Is not air the whole of our habitation as mortals? Is there a dwelling more vast, more spacious, or even more generally peaceful than that of air? Can man live elsewhere than in air? […] No other element is as light, as free, and as much in the “fundamental” mode of a permanent, available, “there is.”1

In her book L’oubli de l’air chez Martin Heidegger [The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger] (1983), Belgian-born feminist philosopher, psychoanalyst, and cultural theorist Luce Irigaray engages with the later work of the eminent German philosopher, critiquing Heidegger’s emphasis on the element of earth as the ground of life and speech and his “oblivion” or forgetting of air. The centrality of the earth in Western history of thought, which Irigaray detects in Heidegger’s philosophy, is something we all have experienced. Think, for instance, about the linguistic expressions we use every day to affirm—perhaps inadvertently and yet effectively—the “supremacy” of the earth over other elements, and what appears to be its instrumental role in the development of human civilization. When we think of Western history, which is a history of nation-states, we think of the export (or, more often, the violent imposition) of a political structure characterized by military and bureaucratic control over patches of land. And the characters of such a history, that is to say, those who inhabit these patches of land, swear allegiance (and sometimes kill or die) in the name of that abstract concept, which is the Motherland or the Fatherland.

Luce Irigaray

And yet, Luce Irigaray argues, behind a philosophy that never leaves the ground—”whether it be that of the earth or that of logos”2—there is something amiss. Heidegger, and with him Western philosophy, have indeed forgotten to think of air, and by doing so, think of the medium in which all worldly things exist. Has the philosopher forgotten to take a breath?—she asks herself. In her words: “Air would be the substance of the copula that would permit the gathering-together [le rassemblement] and the arrangement of the whole into the life and Being of man, and permit his habitation in space as a mortal.”3 In the same book, she also wonders whether the air is feminine, since it gives every living being subsistence, and because it is unrepresentable and fluid—not rigid, like the earth, Heidegger, and Western philosophy.

These ideas—the repositioning of air and the re-reading of a basic principle in Western metaphysics—were key for the conceptualization of Notes on Air at Salt Beyoğlu, an immersive installation and research project conceived and designed by the interdisciplinary agency 2050+.

Notes on Air strives to recenter air by giving presence to an element that otherwise “doesn’t show itself”, “escapes appearing as a being”, and thus “allows itself to be forgotten”4—what is out of sight can very easily fall out of mind. For us at 2050+, an agency of architects, designers, and curators, the research process behind the installation began with a series of pivotal notes on air borrowed from the worlds of environmental studies, spatial practices, and philosophy, challenging the idea of air as a void or an absence. Here are some of these tenets:

Air is a space. More precisely, the thin layer of air we inhabit is the troposphere, the lowest part of the atmosphere (it contains 75% of its total mass), in direct contact with the Earth’s surface. This layer, which varies in thickness between 8 and 14 km depending on time and location, is where most weather phenomena occur.

Air has materiality. It is laden with particles that, despite evading the human eye, remain a constant presence in our lives. These particles create a fundamental condition for existence (breathing is living), while also harboring the potential for lethality. This is especially true for particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) and 10 (PM10)—pollutants with diameters of 2.5 and 10 micrometers, respectively (for scale, consider that the diameter of the average human hair would be 30 times larger than PM2.5). The size of these particles makes them especially hazardous, as they can reach the bronchi, the trachea, the upper respiratory tract, and even the bloodstream.

Air toxicity is a product of the Anthropocene, and it affects humans and other-than-humans alike: animals of course (humans included), but also plants and natural environments at large, thus turning toxicity into a condition that “connects environmental vulnerability with spatial and social factors.”5

Deposition of PM2.5 from indoor air by ornamental potted plants (left) and deposition patterns of PM2.5 particles in lungs (right)

Air (and air toxicity) is transcalar. This makes it impossible to observe air from a fixed point of view or at a fixed scale—air is an element that is both microscopic and macroscopic, and its reach extends from local to planetary.

Air (and air toxicity) is transborder. The “floating bodies”6 suspended in the air move according to a complicated transport system that follows the mechanics of the climate and is indifferent to human-made borders. From this, it follows that the effects of pollution are redistributed according to a meteorological process rather than a geopolitical one, where “the space of violation is separated from the space of its repercussion.”7 Those least responsible for emissions might be (and often are) most susceptible to its destructive effects, while those most responsible may remain (and often do) unaccountable and unpunished. As architect and researcher Adrian Lahoud has put it, “The earth’s climate loosens the bond between cause and effect; it breaks the link between attribution, responsibility, and, potentially, justice.”8

Air is a common. It is a shared domain where the actions of one region reverberate across vast distances, and by virtue of its communality, collective actions are imperative to ensure that clean and breathable air is a universal right for both present and future generations.

Finally, air (and air toxicity) calls for forms of environmental attuned sensing— strategies for detecting that expand the ways in which air can be perceived beyond quantitative data and the realm of science. Unclean air can be studied and monitored through quantifiable data and scientific tools that “make it visible” (i.e., detectable and observable). Yet, “vision is not the only way of knowing.”9 As feminist architect and scholar Nerea Calvillo argues:

“Science accounts for this accumulation [of the infrastructures, devices, practices, and bodies that make up the air] through numbers and concentrations, but this account only provides for one condition of pollution, as well as suggesting technoscientific stories as ‘solutions’ concerned with cleaning it through massive geoengineering projects. In a similar manner to climate change, numbers become too abstract and detached from reality for people to engage with them in meaningful ways.”10

To bridge the gap between understanding and acting, Calvillo argues, it is necessary to challenge “what counts as evidence in toxic regimes”11 and expand our “regime of perceptibility”12 to practices that are sensorial, situated, and embodied, as well as cognitive and visual.

With these powerful considerations in mind, the challenge we set for ourselves with Notes on Air was to conceive a project that could account for all these intricate layers. We worked towards an installation that embraces the multiplicity of ways in which air and air toxicity can be conceptualized, endured, and dealt with. Through this aesthetic and artistic exploration, we sought to give presence to an element that is typically invisible, intangible, and inaudible. Our approach involved a blend of visual, haptic, and sonic experiments, presenting air as both a scientific and a social, philosophical, and affective condition.

The installation is articulated through three components:

An immersive soundscape that envelops the entire exhibition space, inviting listeners to engage with the materiality of the “air-scape.” Commissioned by 2050+ and created by sound artist Francesco D’Abbraccio (aka Lorem), the piece isolates and aesthetically translates various layers of atmospheric information and entities (such as radio waves, electromagnetic currents, living noises, particulate matter, and other forms of information) into sonic experiences. It captures the traces of colliding bodies, small impacts, frictions, and rustling sounds.

The intuition that the aerial landscape is a buzzing ecology of particles that are not only invisible to the human eye but also inaudible came into the conversation with eco-toxicologist Prof. Dr. Melek Türker Saçan (Boğaziçi University). She suggested that if we could hear the crackling noises generated by the countless chemical reactions triggered by pollutants in the air, we would be much warier of their presence and, thereby, their effect. The truism that “seeing is believing” here is given a sonic resignification.

Central to Francesco D’Abbraccio’s conceptualization was an immersive soundscape to be traversed and explored, which he executed through a 14-channel sound system. This audio technique was designed to transmit sound across various speakers throughout the exhibition space, enveloping the listener in a dynamic auditory experience. Each channel represents distinct atmospheric phenomena. The physical movement of the audience through the exhibition space becomes a mode for exploring the unseen layers of the environment, transforming the listener into an active participant in discovering air as a sonic battlefield, rather than an empty and silent void.

A digital reconstruction of the air-scape in Istanbul, displayed on a screen situated at the far end of the exhibition space, spanning seven meters in width and elevated slightly above eye level. The animation was produced by 2050+ using photogrammetry software, a tool that employs photographic material to survey and map physical environments, measure distances between objects, and ultimately reconstruct them. While photogrammetry is primarily used for physical, solid, and static elements of our built environment, we applied it to evidence and give form to a moving, elusive, gaseous substance: a mass of condensed water vapor in flux. In this way, we could draw attention to the flaws and limits of a science and technology that excel in recording, measuring, and interpreting a specific type of imagery, but whose reliability cracks when used outside its intended scope. Such limits became the basis for an artistic reinterpretation. The result appears as a jagged, spiky digital landscape, functioning almost as a visual counterpoint to the soundscape of Francesco d’Abbraccio. The glitches and vibrations on the screen resonate with the hisses and crackles of the sonic piece, offering two imagined reinterpretations of the air’s invisibility.

Animated reconstruction of Istanbul’s sky (3D model by 2050+)

The last and perhaps most pertinent element of the installation is a series of hanging fabrics that rhythmically punctuate the Salt Beyoğlu space, as if dividing the space into sections. These fabrics, suspended from the ceiling, are subtly swayed by the airflow from Istiklal Street, directly connecting the exhibition space with a portion of public space.

Installation view from Notes on Air, Salt Beyoğlu, 2024

Photo: Gamze Cebeci (Salt)

Photo: Gamze Cebeci (Salt)

The materiality of the hanging fabrics is accentuated by their colors. Each layer is dyed with a unique hue, corresponding to differing levels of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air (estimate based on 2019 averages). This spectrum, ranging from light yellow (indicating almost zero micrograms) to deep purple (a concentration of 19 micrograms and above), is frequently employed to illustrate PM2.5 particle concentration in the atmosphere.

Source: The Guardian ©OpenStreetMap

Maps such as those published by The Guardian in 2023 have the advantage of condensing complex scientific data (i.e., the concentration of micro-pollutants in the air) into a form that is readable and emotionally impactful (via a color gradient). The issue of “data literacy” (i.e., the ability to read and interpret the language of data) is central here. A telling example is the color purple, which represents the highest degree of particle concentration in the air (i.e., the most toxic) and that only in recent years has been included in the spectrum of the color-coded air quality index, replacing the color red. According to data visualization designer Giorgia Lupi, purple is a color that evokes a sense of unsettling lividity: “Think of bruises, and the color purple on skin when talking about disease. It is another level. It’s darker, and a more advanced stage [than red], if you will.”13 Red is indeed “the color of alert, of stop signs,”14 but in the era of climate catastrophe, even red is not enough.

Color gradient scheme (Courtesy 2050+)

Color gradient scheme (Courtesy 2050+)On the other hand, despite their immediacy, these types of maps fail to provide a granular understanding of air toxicity. They flatten out any kind of social and cultural specificity, allowing only the human convention of political borders to emerge. Playing once again with the notion of limits and flaws (this time not through photogrammetry as a tool, but through cartography as a representational medium), we decided to adopt this conventional way of visualizing air toxicity based on color coding and give it tactile presence through the hanging fabrics at Salt Beyoğlu.

Detail of the graphics embroidered on the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

Detail of the graphics embroidered on the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)In addition, each layer of hanging fabric depicts a key pollutant that is notably harmful and widespread in Istanbul’s air: nitrogen dioxide, ozone, carbon dioxide, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide. Functioning as fluctuating boards, the hanging curtains overlay three types of data: the concentration of each pollutant in Istanbul over the course of one year (2020-2021); the anthropogenic sources responsible for the high concentration of that pollutant (construction, ore extraction, industrial activities, burning fossil fuels, etc.); and the effects of that air pollutant on human and non-human health (asthma, fatigue, reduced oxygen in the blood, dizziness, etc.). Crucially, these layers of scientific information, which rely on numbers, hard data, and quantitative analysis, are represented on the hanging fabrics through embroidery—a technique traditionally associated with domesticity, female artisanship, warmth, and intimacy. Not only is the intangible condition of air toxicity given haptic presence, but also the language of science used to describe it is softened, rendered tactile and more accessible.

Detail of the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)

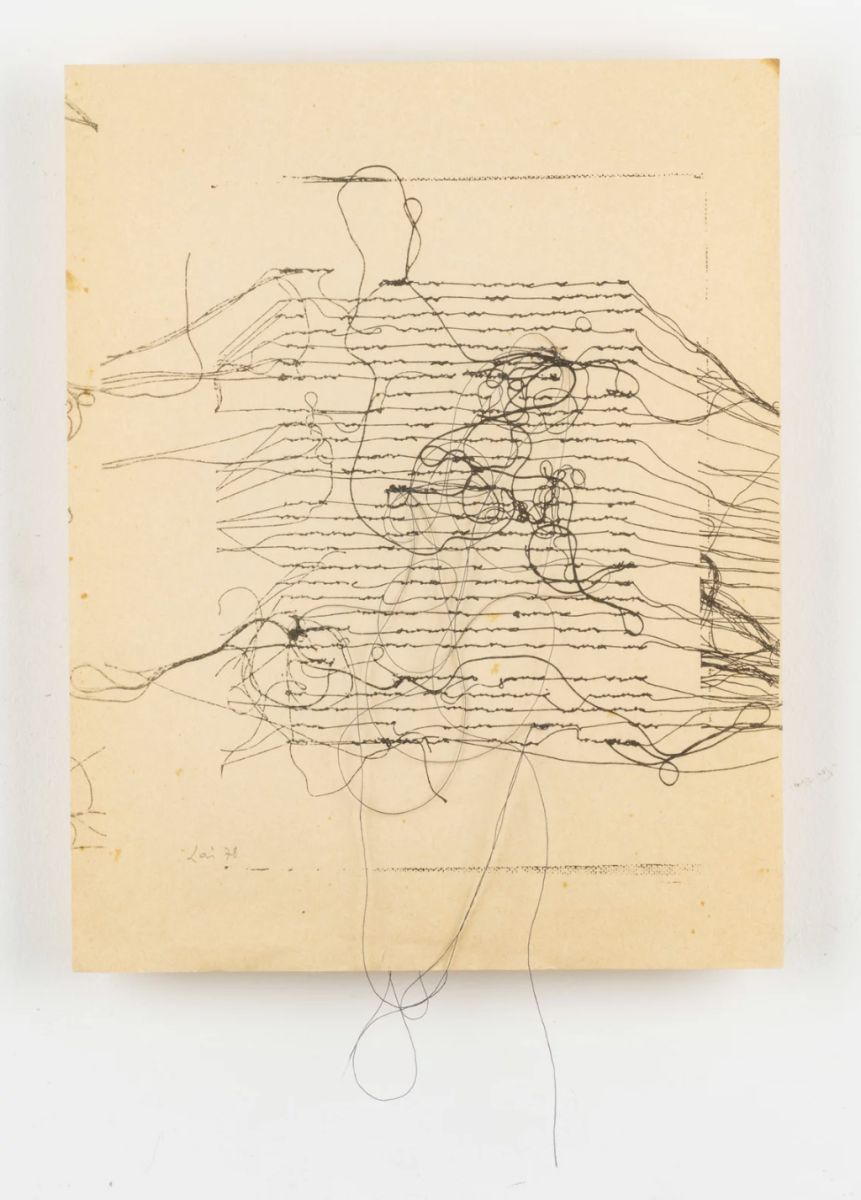

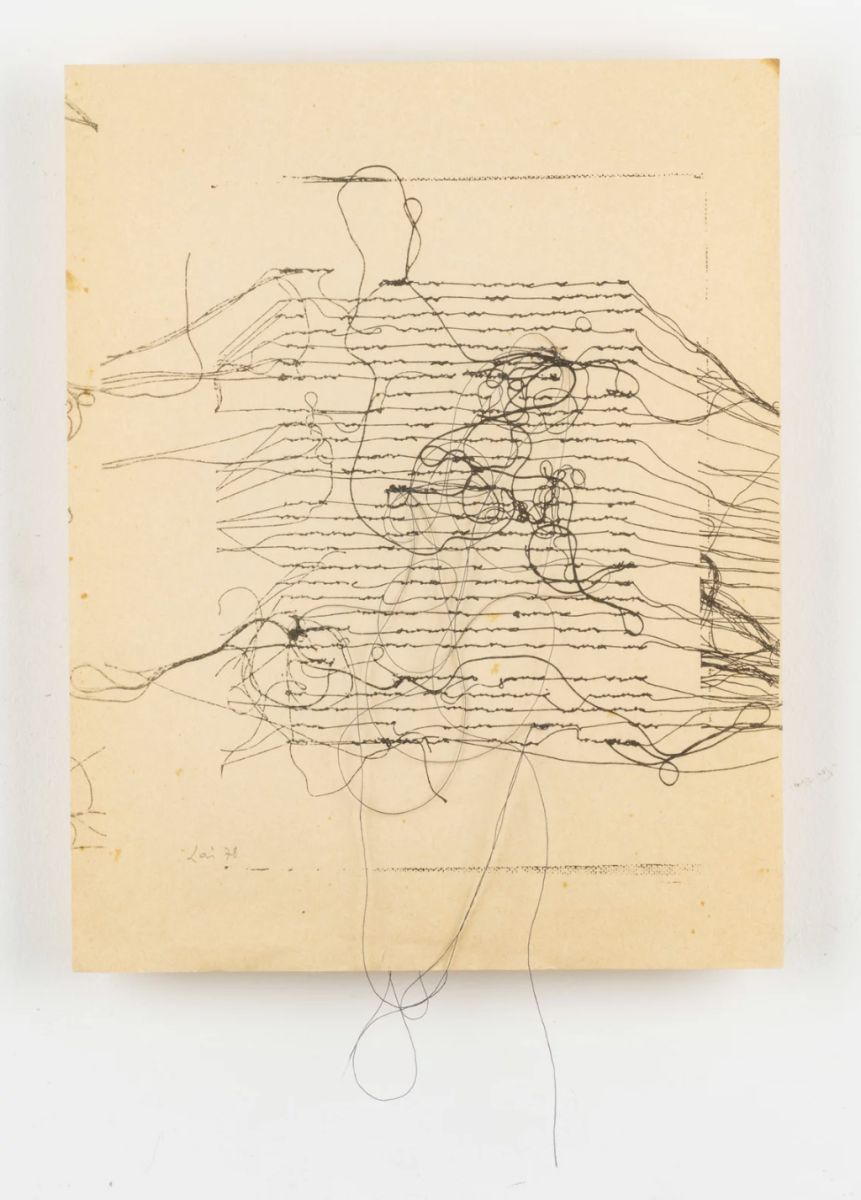

Detail of the hanging curtains (Courtesy 2050+)The idea of weaving stories of air toxicity onto the fabrics was inspired by Sardinian artist Maria Lai, best known for her textile works and described by critic Giorgio Di Genova as a “poetic amanuensis of sewing.” Reclaiming ancient Sardinian traditions with sensitivity and talent, Maria Lai gave artistic depth to a practice traditionally associated with the ordinary and domestic, and transformed embroidery into a tool of personal expression and emancipation. In her famous textile diaries, her thoughts and impressions are inscribed with a thread and needle: some words can be deciphered on the fabric pages, but most remain unreadable. Similarly, the embroidered data in the exhibition can only be partly interpreted: the size of the hanging fabrics makes it difficult to read them all at once, and visitors have to content themselves with the sense that they have grasped an impression. It is precisely within this space of suspension—where rational understanding needs to halt and techno-scientific tools fall short—that we found a fitting metaphor for our approach to air and air toxicity: suspension as a method.

Maria Lai (Photo: Elisabetta Loi)

Courtesy Fondazione Stazione dell’Arte

Courtesy Fondazione Stazione dell’Arte

Maria Lai, Untitled, embroidery on xerography, 1978

With these three interrelated components (the sonic, the visual, and the haptic), Notes on Air wishes to introduce novel methodological, conceptual, and discursive frameworks for contemplating issues around air and air toxicity. Crucially, it does so within the context of a cultural institution—thereby fulfilling the responsibility of contemporary art spaces as forums for interdisciplinary discussion. In this sense, Notes on Air is not only an installation but also a call to responsibility—for visitors and cultural institutions alike—and an exploration of how the languages of art, science, and activism converge within such a forum.

Ultimately, Notes on Air is a hymn to the potential for generating new interpretations of the world. Much like Luce Irigaray in L’oubli de l’air, and many other scholars, artists, and anonymous citizens who have sought to bring to the fore novel protagonists and questioned dominant narratives (be it the hegemony of the earth over other elements or of certain forms of artistic expression over embroidery), Notes on Air presents a similar challenge: interrogating the status quo to weave alternative interpretations of reality—a necessary premise for any attempt to change it. This is now more vital than ever, both within and beyond the realm of cultural institutions.

Exhibition conceived and designed by 2050+ (Che Facchin, Guglielmo Campeggi, Erica Petrillo, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, Kamil Dalkir, Meera Badran, Nils Grootenzerink, Sara Barbini)

Sound Designer: Francesco D’Abbraccio aka Lorem

Production: Emirhan Altuner

Salt project team: Eylül Şenses, Emirhan Altuner, Fatma Çolakoğlu

Advisor: Prof. Dr. Melek Türker Saçan (Boğaziçi University)

2050+ is an interdisciplinary agency based in Milan whose work revolves around diverse forms of critical spatial practices at the intersection of technology, politics, and the environment. Founded in 2020, 2050+ has carried out a range of projects spanning curatorial and research practices, exhibition design, and architecture. 2050+ regularly collaborates with various institutions to create temporary installations, films, public events, and editorial initiatives. The agency is also committed to independent research projects, including short films and critical texts featured on numerous publishing platforms. These projects often address the relationship between data and the material world—a line of research that 2050+ explores in the context of ADS8: Data Matter, a research and design studio at the Royal College of Art in London.

Erica Petrillo is a curator and researcher with a background in political philosophy and social sciences. She collaborates with the interdisciplinary agency 2050+ and works on several independent projects in parallel. She has curated public programs and exhibitions for various cultural institutions in Italy and abroad. Before joining 2050+, she worked at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where she was responsible for the series of monthly R&D Salons; co-curated Broken Nature, the XXII Triennale di Milano in 2019; and was the 2019-2020 curator-in-residence at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht.

- 1.Luce Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger, trans. Mary Beth Mader, London: Athlone Press, 1999, p. 8.

- 2.Ibid., p. 7.

- 3.Ibid., p. 12.

- 4.Ibid., p. 5.

- 5.Nerea Calvillo, "Particular Sensibilities," e-flux Architecture, October 2018.

- 6.Adrian Lahoud, "Floating Bodies" in Eyal Weizman and Anselm Franke (eds.), Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014, pp. 495-518.

- 7.Ibid., p. 508.

- 8.Ibid.

- 9.Calvillo, "Particular Sensibilities."

- 10.Ibid.

- 11.Nerea Calvillo, Aeropolis: Queering Air in Toxicpolluted Worlds, New York: Columbia University Press, 2023.

- 12.Nerea Calvillo, "Political airs: From monitoring to attuned sensing air pollution," Social Studies of Science, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2018, p. 374.

- 13.Neda Ulaby, interview with Giogia Lupi, "Purple is the new red: How alert maps show when we are royally ... hued," NPR Health, June 8, 2023.

- 14.Ibid.