Pigeons are People

CAN ALTAY AND NOVEMBER PAYNTER

27 Ocak 2014

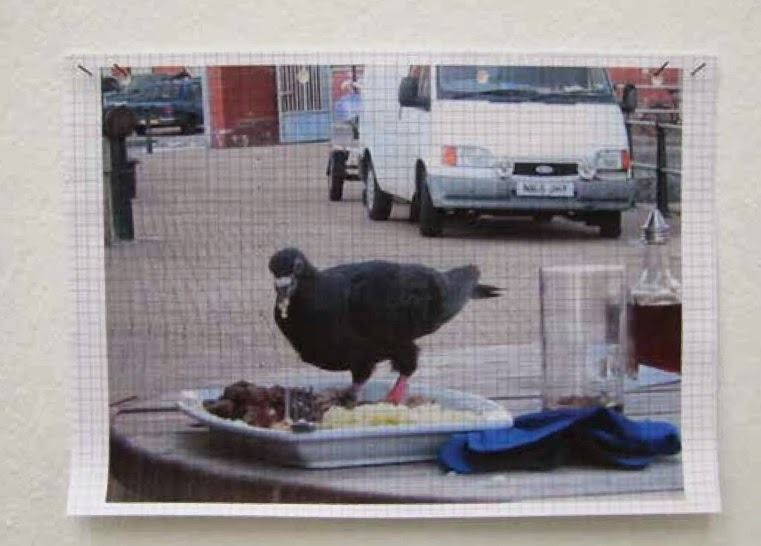

Can Altay, ‘This Pigeon went to the City’, ‘This Pigeon went to the Forest’, 2008

Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

November: I would not normally propose to conduct an interview that refers to projects in chronological order, but we have formed a relationship which encompasses at least three major exhibitions, as well as numerous conversations, screenings and other collaborations. Within this trajectory I am interested in how your position has developed in relation to the space of the gallery and exhibition structures, and in particular with respect to how you collaborate with others and how the audience is considered.

So if we may start from the ‘beginning’ – I remember seeing a work of yours the first time I travelled to İstanbul in 2001, in the exhibition “Becoming A Place” at Proje4L. It really inspired me and stayed in my mind because up until that point it was the only art work/installation I had seen that seemed to deal with the physicality of a city condition that I was experiencing for the first time.

Can: “The Secret of Kindness”, the piece you are referring to was a direct attempt at intervening in the exhibition itself, shaping its flow and its viewing to a certain degree. At the same time the piece was commenting on the city, Proje4L’s position as an institution and the institute as a notion, as well as potentials and possible shortcomings in relation to its immediate surroundings1 (these were also some of the main concerns of the exhibition’s curator Vasıf Kortun). This was one of my earlier attempts at intervening directly at exhibition- making, with serious concerns about how the space and experience of art-works can be altered, or filtered, and all rooted from a wider (if I may dare to say) philosophical concern. It had to do with boundaries, how these boundaries were performed in many different ways, and how they could be shifted, or even transgressed along with an acknowledgment of their existence. So for me, the gesture of dividing the whole space with a semi-transparent curtain (with a written statement on it) was no simple gesture, it was a defining movement that created a filter through which to see the other artists’ works, but it also became an almost invisible piece which was in actuality very present.

I recall that many viewers saw this curtain as part of the architecture, while others didn’t notice it at all. I should admit that the project fell a bit short at the time, in that it was delayed as an ongoing conceptual process for some years, but it did later re-surface to focus more on the formation of exhibitions, and the processes of reconfiguration. So what this exhibition experience led to was the forming of a larger body of work within my practice. It was the first time that I published on the “minibar” phenomenon2, in the book that accompanied the show. Erden Kosova had made an interview, which was a spin-off from the ABAP project Serkan Özkaya initiated, that we were both a part of. Amongst our group correspondence, Erden had picked up on my reflections on the minibars (which I was developing for a research/theoretical work on the city) and asked to publish an interview in the book. This text received quite a bit of attention in the coming years, and eventually the work around minibars became a milestone within my story and the story of my works.

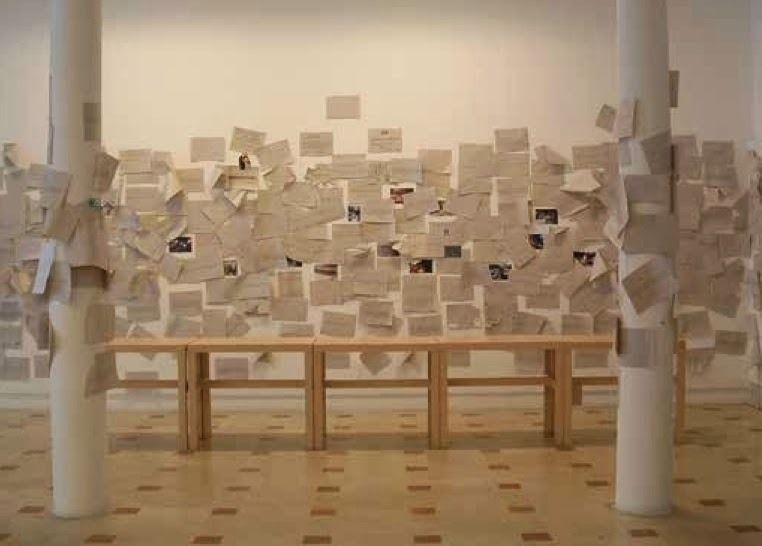

N: We first worked together in 2003 when I invited you to present the “Minibar” project in an exhibition called “Making Space” that I curated for Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center. The show aimed to open up the idea of using and experiencing the urban context beyond the planners’ intent, in more explorative and improvisational ways. I knew that we would likely show “Minibar” as a slide projection, but your participation went well-beyond the addition of a requested art object and ended up as an interactive arena where the public were invited to comment on their experience of authoritarian structures in the urban sphere and how they could be contradicted. In the end the gallery walls became plastered with texts on the topic and the public seemed to really relish the opportunity to have and share a voice.

The same year you presented “‘We are Papermen’ he said” at the İstanbul Biennial. Due to its location on the pedestrian street Istiklal Caddesi Platform had a very different audience to the Biennial; so I am interested to ask you what it meant to show work in these two different venues and contexts, and also about the collaborative nature of the work at Platform that was created with your sister Deniz Altay, and in the end also with the public.

C: I guess I can say that different modes of collaboration were at stake. The collaboration with Deniz Altay involved bringing together our research and interpretations around a common area of interest, as we were both working on the minibar phenomenon. This involved taking excerpts from a set of interviews that were mainly conducted with the young people who hung out at the minibars, and trans- forming this set of correspondences into the basic unit of the piece. We composed a wall narrative as a launching device, but multiplied copies of these statements -ranging from personal historical notes, to general commentary, to drunken drifts- to be at the audience’s disposal. Additional papers and two rolls of sticky tape left out on a table were our way of providing the basic tools for the piece to grow through time and in the exhibition space. All of these were inspired by the nature of how the minibars came about in the first place, and how a production of meaning (and function) grew to encompass a totally unexpected territory, by simple gathering, drinking, and making use of existing physical elements that were initially there to draw boundaries, and mark private territories or public infrastructures. Bringing all these statements from an unknown scene in Ankara, to the most crowded pedestrian street of İstanbul, where Platform Garanti was located, and the very strangely welcoming nature (as you recall there were hundreds of random passersby going in and out that space) of the gallery itself, gave way to a kind of interpretation and reconfiguration that was performed solely by the audience/viewer/visitor/makers. Eventually the piece grew out of control, there was conflict within the system (just as in the minibars) and roles and actions had to be negotiated. So what seems at first glance to be a simple gesture of participation, was actually a way to reflect on the minibar phenomenon from within the space of art.

“‘We’re Papermen’ he said” (2003) was quite similar in that again the installation was pretty much shaped by the issues being discussed within the work. You are right to suggest that the Biennial had an altogether different audience, more distanced to the “streets” so to say. But the work was also partly tackling the problematic relation- ship between artist (myself) and subject (paper men)3. The distances and the parallel layers that made the city, and that enabled a profession such as the paperman’s to deal with waste, informality, and neglect, and these practices formed a part of what I was trying to work around. On the other hand, as part of the piece, the viewer/visitor was now invited to go through an excavation of pages of diary material, from which they could pile up their own sequence and story, and which included accounts (from those that were very personal, to scientific research findings, to newspaper clippings) and attempts to encounter papermen and figure out their operations in big cities in Turkey. So in a sense the audience now had access to a pile of things (which can also be seen as the artist’s garbage), from which they made something for themselves, basically to take home and read. Here the collaboration if we may call it so, was still quite choreographed or framed, but I still had no control over who took what and how one read the storyline. Well, one can say this is always the case, but the relation between work and viewer was almost materialized with this gesture.

N: The next exhibition we explored together at Platform was “Art For…” (implying Art for export) a series of three shows that looked at the burgeoning interest in Turkey and its contemporary art scene by those working within the arts in Europe. The series of three shows started with two that hosted works which had been shown in Europe or elsewhere but had yet to be shown in Turkey and ended with the exhibition “Normalization”, which pushed the notion further to delve into a variety of concerns about the driving practice of ‘normalization’ both politically, socially and personally. The first two shows in the series saw some works being recreated for our space, but in more modest ways, such as Cevdet Erek’s work “The 2nd Bridge” (2003) being scaled down and a wall painting by Haluk Akakçe first shown in Italy reinstalled in a more confined space; these ‘mimickings’ and the idea of working to normalize our own process of curating the show, resulted in your installation that initially condensed the first show into the second and then the first two shows into the third. Again the collaboration involved various other participants as you included works by the other artists in the exhibition in your own installation, sometimes asking them to recreate their own works within this new context. This shift, from working with the audience to working with other participating artists in the same exhibition as yourself, seems to be a practice that now drives many of your installations. Can you describe how the installation in “Art For…” came about, how it was to work with a group of artists selected by the curators and also how this experience fed into following projects?

C: One can see it as a more violent gesture from my behalf in comparison to the previous pieces, but looking back I can say this was where the three pieces we’ve discussed so far culminated. In a way the questions around exhibition-making and exhibition-space, return to the scene, bringing along the “unpredictable reconfiguration” (to quote Engin Öncüoğlu) that was evident in the works that looked into the city for their subjects. It also brought forward questions of authorship, and the boundaries between the artist/work of art/ exhibition/audience, it’s like, where do they start and where do they end? Or do they end? I was also a bit obsessed with the pre- conceptions of how the spaces for art function, such as the periodical tabula rasa, the complete cleaning up of the space before each new show, which relates to the notions of white-ness and neutrality, which are not true! The physically claimed neutrality is a way to undermine the socio-economico-political frames and infrastructure of how art institutes function. So this action of condensing each exhibition and keeping them in the space, with samples from the original works, photographic documentation of installations, and existing elements or furniture to be re-shaped and re-composed within the same space, but for longer than usual durations and in a periodically growing sense, was a way to intervene in and reconfigure such pre-conceptions. It was also a challenge to the ‘very short-term memory’ not only in art, but in life and politics, in a sense how the city or the country does not tend to accumulate knowledge of its recent past, and how it tries hard not to relate or learn from its recent past. In the end the whole project involved many artists’ blessings, and agreement, as the original pieces were to be re- configured. Not everybody agreed to this, I guess 2 out of 18 artists disagreed, so I ended up showing only photos of their work, taken by other people. However these were balanced with the more inventive contributions, such as Leyla Gediz’s painting. The painting she had shown in the first exhibition of the series belonged to a collection who did not want to take the risk of showing the piece within my constellation. After discussing this situation, Leyla painted a detail of the original round canvas, in 1/1 scale again on a smaller round canvas, which introduced further thoughts of originality, reproduction, and art historical references via the painting being a ‘detail view’ to the first painting. This was an expansion to the original intentions, and really made the installation ‘grow’ and also allowed me to act more freely in the second round of condensation, of making the “Normalization” piece.

N: The work you proposed for the exhibition “New Ends Old Beginnings” that I curated in 2008 for the Bluecoat gallery in Liverpool was a very different kind of piece. This time the curatorial request was that you respond to your experience of having spent time in Dubai. Was this an unusual experience for you given that so many of your art installations deal with the space of the gallery and the cross-referencing of your work in relation to the other works being exhibited? Perhaps you can describe “Deposit (Spring Deficit: After Dubai, After Hammons, and after the politics of white noise)”, 2008 and how it came about to be a more formal sculptural embodiment?

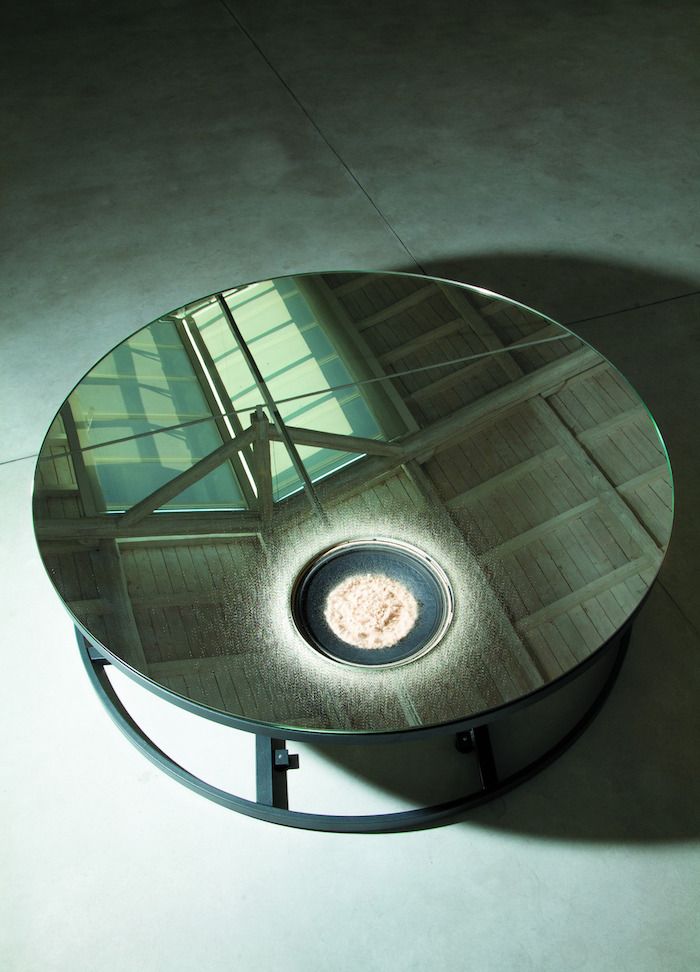

C: I think that cross-referencing still exists in the piece, but I can also say it was my take on making a self-contained work, producing an object/system, and taking responsibility of its existence, in the world of singularities. That cross-referencing eventually exists as the mirror surface captures its surrounding and those who are looking at the piece. But perhaps I should first tell a bit of the ideas that made it. “Deposit (Spring Deficit: After Hammons, After Dubai, and after the politics of white noise)” is a sculpture, which operates mechanically as a fountain, a fountain that mobilizes sand instead of water, a sand fountain. The sculpture works through the range of potentials a fountain holds. From historically being the key representation of wealth and power, to its religious connotations, to the idea of the ‘spring’; from its uses as public service, charity, to symbolic prestige, to its function as acoustic blockage in meetings on diplomacy; from its importance in Baroque to its unavoidable resonance in 20th century art. I titled the piece before the global crisis emerged, but I see it resonating well with the conditions of today. An aspect related to Dubai is its reflection of Western Discourses; it is a sort of mirror- world where certain things reflect obliquely, or are simply reversed; all the while what constitutes both sides remains as a set of conditions that are rooted in simple capitalism as much as its advanced corporate development. The fountain that remains a fountain but strives to function with sand instead of water is an attempt to pin down that moment of mirroring, not only to illustrate but to commentate via a singular sculptural object (a totality – that circulates grains of sand) instead of other representational or documentational tools and narratives.

The process of making the piece was also interesting. After your invitation/commission and after deciding on the main principles and title, for a long time I discussed with Paul Bartlett, a friend and robotics wizard, about possible ways of making the fountain fully function: as a closed circulation system that works with sand. We looked at mechanical devices used for grains or sanitary powders, I also started looking into what else was available, but all the time the piece was growing more complex and much larger than necessary. It was a focused brain-storm sketching session with Aslı Kalınoğlu, during a train-ride, that first made me realise we could simplify the piece by chopping out certain mechanisms, forms and all that was unnecessary, until we came to the point that the movement of sand was not necessarily through circulation (which was Hammons’ way), instead it could be achieved through sound - and we had already considered sound as integral to the piece. So, sand, sound, mirror, and pond or pool came together in the final form as Deposit.

N: I am intrigued to learn more about another recent installation that you have created for the exhibition “There is no Audience” curated by Adnan Yildiz. Although I did not see the exhibition, from the documentation it felt very much that your structures created a pivot for the other works in the show to gather around. How do you see the relationship between the other works in this exhibition and your intervention in terms of the way it changes the environment, via its semi-functional gesture, for all the participants? Was your response a comment on the ironic proposal of the title?

C: “CloudCrowdCloud” (2009) was the piece I developed for that show at Montehermoso. It follows a body of work which I broadly call “setting a setting”. Basically looking into the exhibition space, and the art institute, via their promise of public-ness, or rather asking whether the art context can still offer at least a simulation of a public space. And to do this the piece reproduces very fundamental architectural elements, becomes something between a backdrop, sculpture, an architectural setting, open for use or viewing, but also employs an additional narrative, which brings the piece from mere furniture to a discussion. Here, this narrative is supported by a footnote, a series of posters pasted all over the back surface of the structure, telling about a scene from the film “3 Days of the Condor” which suddenly surfaces questions about where we stand and how the work can be seen. The addition of a photo that shows a pigeon descending stairs in the town-center further complicates things. The whole setting locates at a very central spot in this corridor-like space -there is also the curator’s contribution to an extent here, especially in terms of other artists’ works and how “CloudCrowdCloud” locates amongst them. The piece forms further corridors and thereby multiplies a small space, into an experience of complexity. This was something I previously tried in my solo-show at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien (“Setting a Setting / Forecasting a Broken Past”), where the setting was formed to bring together very different works of mine, by placing these large steps, like a mini- auditorium, which created sub-spaces and supra-spaces in a very small room. I guess these works all try to construct certain complex systems, to be inhabited and used in some ways, determined or not, and also to let go of their possible interpretations through use. “A Damaged Plane” which played the central role in my solo exhibition at Spike Island (“Ey Ahali! / Setting a Setting / Letting a Setting Go”) further embraces this reconfiguration, through its open and invited uses by, amongst others, musicians and sound artists, where each performer had interpreted the setting, while having to reconfigure their own practice and their own habits of performance, as these settings are always slightly dysfunctional.

N: The previous question leads into a larger and ongoing conversation about your position as an architect/artist and how you relate/explore/distinguish your roles within each discipline. The 4th Architecture Biennale in Rotterdam, must have presented a new direction in that you as the co-curator were inviting others to respond to questions that you have been raising within your independent practice. How do you find balance and remain focused when your own role appears to shift and change so often and how do you manage to keep others engaged and responsive to these ambiguities of authorship?

C: That’s something I haven’t resolved fully, and I am questioning more and more whether I should distinguish my position in terms of these defined disciplines. I am deeply interested in the historical constructions around art, and see my work primarily within that universe. On the other hand I am engaged in thinking about ‘space’ as that vital prosthesis which is manifested always already in how we live, and which can only be seen as a complex construct that involves politics, economics, and the social along with physical presence. And cities as ever-changing, multi-layered systems, like the art context, where I have high hopes and belief in that their ‘ways’ need constant challenge, and their rules and pre-conceptions need to be pushed for further re-configuration if not transgression. There is not necessarily an ultimate, final, best condition, but spaces deserve making and re-making, if we agree that there are still things that one is able to achieve, and that a better way is always a promise.

The exhibition “Refuge: architecture for unbound spaces” which I co-curated with Philipp Misselwitz, initially for the 4th Rotterdam Architecture Biennial, and later for our own expanded version in İstanbul, titled “Open City İstanbul”, was a project that looked into cities mainly in the region of Turkey/Middle East (with their counterparts in Europe or elsewhere). We looked at architectural and urban practices that really challenged the existing modes of practice, while producing work that fundamentally holds a clear position against the power-oriented production of space (be it in neo-liberalism, state oppression, or boundary-maintaining), practices that place themselves in a grid full of conflicts, and still act to find inventive ways of providing-, preventing-, improving-, dismantling- the conditions of “refuge” when and where necessary. It was also a way of valuing this work, providing alternatives to given modes of practice, and also bringing forth severe issues about cities, spaces, and of course people, that are still in need of fundamental rights, spatial justice, and if we may call it so, a civic existence.

Another project that I have been working on, which is called “PARK: bir ihtimal” in a sense brings together all these discussions about space, authorship, collaboration, the city and public space, for the first time, taking place literally in ‘the open’. This project acts within the immediacy of a public audience, as it is located in a park, in the center of İstanbul. It is a small park, yet it is quite crowded, and forms a complex eco-system almost mimicking the whole city. What is again at stake is a kind of collaboration, initially with the group of contributors I invited, and the public, the audience, the passer-by, but also the people who live and work at the park, both officially and unofficially. The project also clashes very individual practices into a whole, to the point that you don’t necessarily perceive any autonomy within each piece. This has to do with the way these works are held together, but also with the very nature of the park, in which every object, every thing, every body, can become something between a contribution and an intervention, which can then add on to this complex eco-system. I invited Nils Norman, whose ideas on public space, ecological discourse, DIY, and the so-called “creative classes” contribute perfectly to the context; Ceren Oykut with her landscape drawings that depict the urban transformation of İstanbul vividly; the publishers and gardeners collective Sinek Sekiz grow vegetables in our urban orchard; the design studio Future Anecdotes provided the signage which is an integral element in the whole, as well as the publication; and a collective work-force of a small group of young artists and architects who have collaborated with me to develop the pieces and elements that bring the pieces together as well as relating the whole project directly to the park context.

N: To conclude, there is one question I have wanted to ask for a while and especially since we recently composed a piece for DOMUS together along with Asli Kalinoglu that referred back to a couple of works including “Exercises in Sharing: Aping Me Aping You” (2007). Where, when and how did your fascination with pigeons come about?

C: Well, I guess it starts from a certain fear and hatred that I eventually reconciled. But the first piece I can recall, was a small drawing which accompanied a photograph, taken at a train station in Germany, dated 2004. Later on, “Exercises in Sharing” became this wider frame within which I presented a pack of chips (the local delicacy) to an urban fox (the local beast) in Cork; collected a vast amount of images of plants and animals that inhabit cities, including that photograph of a pigeon eating from a plate in a pub in Bristol; and proposed an immaterial monument that would partially shatter the possessiveness of pigeon-breeders in Cairo. But this piece with the bread and the defensive pins was the first in the series of works which for me kept on swinging between polemic and archive; between constellations of images and questions of display; between gestures that relate to the ages old separation of “man” (I don’t say human) and “animal”, to issues of sovereignty, hegemony, and freedom. Yet, to answer on a slightly different note: pigeons are people.

- - -

A conversation between Can Altay and November Paynter, 2010.

First published in Pigeons are People, 2010

ISBN 978-3-86895-126-4

So if we may start from the ‘beginning’ – I remember seeing a work of yours the first time I travelled to İstanbul in 2001, in the exhibition “Becoming A Place” at Proje4L. It really inspired me and stayed in my mind because up until that point it was the only art work/installation I had seen that seemed to deal with the physicality of a city condition that I was experiencing for the first time.

Can: “The Secret of Kindness”, the piece you are referring to was a direct attempt at intervening in the exhibition itself, shaping its flow and its viewing to a certain degree. At the same time the piece was commenting on the city, Proje4L’s position as an institution and the institute as a notion, as well as potentials and possible shortcomings in relation to its immediate surroundings1 (these were also some of the main concerns of the exhibition’s curator Vasıf Kortun). This was one of my earlier attempts at intervening directly at exhibition- making, with serious concerns about how the space and experience of art-works can be altered, or filtered, and all rooted from a wider (if I may dare to say) philosophical concern. It had to do with boundaries, how these boundaries were performed in many different ways, and how they could be shifted, or even transgressed along with an acknowledgment of their existence. So for me, the gesture of dividing the whole space with a semi-transparent curtain (with a written statement on it) was no simple gesture, it was a defining movement that created a filter through which to see the other artists’ works, but it also became an almost invisible piece which was in actuality very present.

I recall that many viewers saw this curtain as part of the architecture, while others didn’t notice it at all. I should admit that the project fell a bit short at the time, in that it was delayed as an ongoing conceptual process for some years, but it did later re-surface to focus more on the formation of exhibitions, and the processes of reconfiguration. So what this exhibition experience led to was the forming of a larger body of work within my practice. It was the first time that I published on the “minibar” phenomenon2, in the book that accompanied the show. Erden Kosova had made an interview, which was a spin-off from the ABAP project Serkan Özkaya initiated, that we were both a part of. Amongst our group correspondence, Erden had picked up on my reflections on the minibars (which I was developing for a research/theoretical work on the city) and asked to publish an interview in the book. This text received quite a bit of attention in the coming years, and eventually the work around minibars became a milestone within my story and the story of my works.

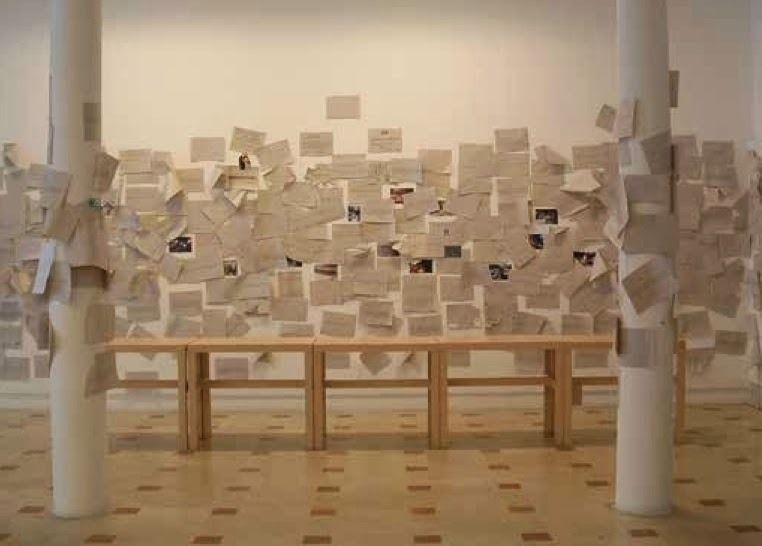

Minibar No Stop, 2003. Making Space, Platform Garanti, İstanbul

N: We first worked together in 2003 when I invited you to present the “Minibar” project in an exhibition called “Making Space” that I curated for Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center. The show aimed to open up the idea of using and experiencing the urban context beyond the planners’ intent, in more explorative and improvisational ways. I knew that we would likely show “Minibar” as a slide projection, but your participation went well-beyond the addition of a requested art object and ended up as an interactive arena where the public were invited to comment on their experience of authoritarian structures in the urban sphere and how they could be contradicted. In the end the gallery walls became plastered with texts on the topic and the public seemed to really relish the opportunity to have and share a voice.

The same year you presented “‘We are Papermen’ he said” at the İstanbul Biennial. Due to its location on the pedestrian street Istiklal Caddesi Platform had a very different audience to the Biennial; so I am interested to ask you what it meant to show work in these two different venues and contexts, and also about the collaborative nature of the work at Platform that was created with your sister Deniz Altay, and in the end also with the public.

C: I guess I can say that different modes of collaboration were at stake. The collaboration with Deniz Altay involved bringing together our research and interpretations around a common area of interest, as we were both working on the minibar phenomenon. This involved taking excerpts from a set of interviews that were mainly conducted with the young people who hung out at the minibars, and trans- forming this set of correspondences into the basic unit of the piece. We composed a wall narrative as a launching device, but multiplied copies of these statements -ranging from personal historical notes, to general commentary, to drunken drifts- to be at the audience’s disposal. Additional papers and two rolls of sticky tape left out on a table were our way of providing the basic tools for the piece to grow through time and in the exhibition space. All of these were inspired by the nature of how the minibars came about in the first place, and how a production of meaning (and function) grew to encompass a totally unexpected territory, by simple gathering, drinking, and making use of existing physical elements that were initially there to draw boundaries, and mark private territories or public infrastructures. Bringing all these statements from an unknown scene in Ankara, to the most crowded pedestrian street of İstanbul, where Platform Garanti was located, and the very strangely welcoming nature (as you recall there were hundreds of random passersby going in and out that space) of the gallery itself, gave way to a kind of interpretation and reconfiguration that was performed solely by the audience/viewer/visitor/makers. Eventually the piece grew out of control, there was conflict within the system (just as in the minibars) and roles and actions had to be negotiated. So what seems at first glance to be a simple gesture of participation, was actually a way to reflect on the minibar phenomenon from within the space of art.

“‘We’re Papermen’ he said” (2003) was quite similar in that again the installation was pretty much shaped by the issues being discussed within the work. You are right to suggest that the Biennial had an altogether different audience, more distanced to the “streets” so to say. But the work was also partly tackling the problematic relation- ship between artist (myself) and subject (paper men)3. The distances and the parallel layers that made the city, and that enabled a profession such as the paperman’s to deal with waste, informality, and neglect, and these practices formed a part of what I was trying to work around. On the other hand, as part of the piece, the viewer/visitor was now invited to go through an excavation of pages of diary material, from which they could pile up their own sequence and story, and which included accounts (from those that were very personal, to scientific research findings, to newspaper clippings) and attempts to encounter papermen and figure out their operations in big cities in Turkey. So in a sense the audience now had access to a pile of things (which can also be seen as the artist’s garbage), from which they made something for themselves, basically to take home and read. Here the collaboration if we may call it so, was still quite choreographed or framed, but I still had no control over who took what and how one read the storyline. Well, one can say this is always the case, but the relation between work and viewer was almost materialized with this gesture.

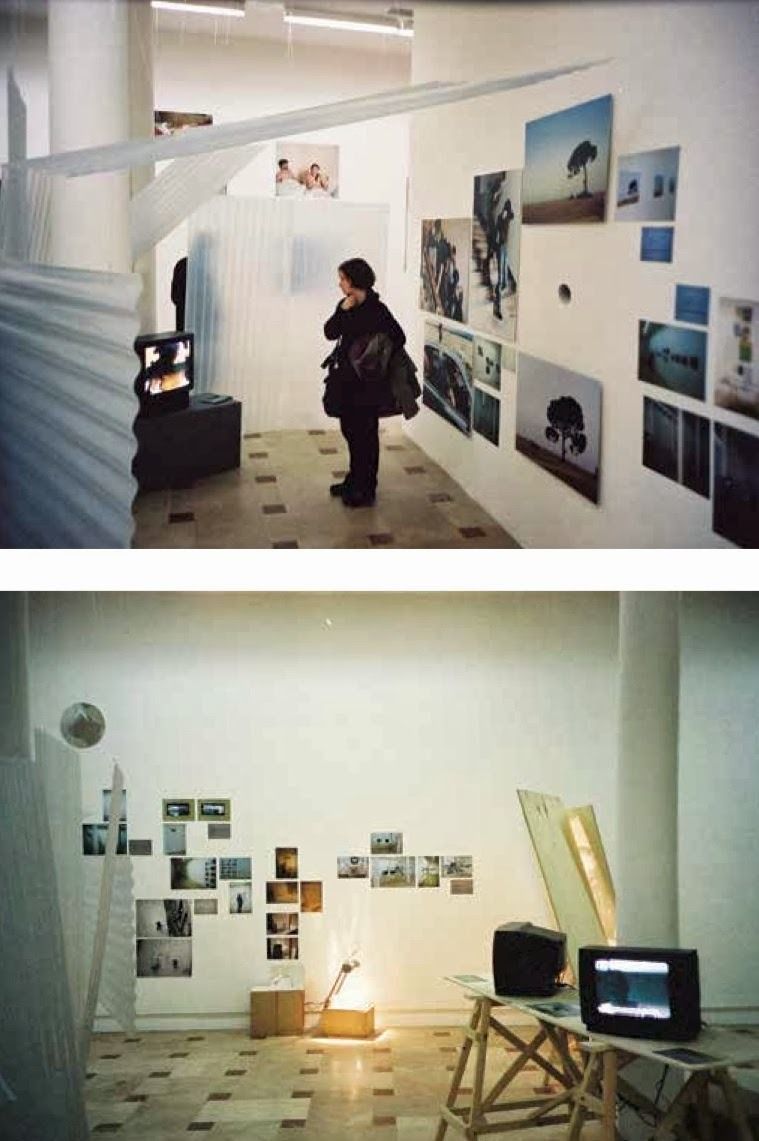

N: The next exhibition we explored together at Platform was “Art For…” (implying Art for export) a series of three shows that looked at the burgeoning interest in Turkey and its contemporary art scene by those working within the arts in Europe. The series of three shows started with two that hosted works which had been shown in Europe or elsewhere but had yet to be shown in Turkey and ended with the exhibition “Normalization”, which pushed the notion further to delve into a variety of concerns about the driving practice of ‘normalization’ both politically, socially and personally. The first two shows in the series saw some works being recreated for our space, but in more modest ways, such as Cevdet Erek’s work “The 2nd Bridge” (2003) being scaled down and a wall painting by Haluk Akakçe first shown in Italy reinstalled in a more confined space; these ‘mimickings’ and the idea of working to normalize our own process of curating the show, resulted in your installation that initially condensed the first show into the second and then the first two shows into the third. Again the collaboration involved various other participants as you included works by the other artists in the exhibition in your own installation, sometimes asking them to recreate their own works within this new context. This shift, from working with the audience to working with other participating artists in the same exhibition as yourself, seems to be a practice that now drives many of your installations. Can you describe how the installation in “Art For…” came about, how it was to work with a group of artists selected by the curators and also how this experience fed into following projects?

C: One can see it as a more violent gesture from my behalf in comparison to the previous pieces, but looking back I can say this was where the three pieces we’ve discussed so far culminated. In a way the questions around exhibition-making and exhibition-space, return to the scene, bringing along the “unpredictable reconfiguration” (to quote Engin Öncüoğlu) that was evident in the works that looked into the city for their subjects. It also brought forward questions of authorship, and the boundaries between the artist/work of art/ exhibition/audience, it’s like, where do they start and where do they end? Or do they end? I was also a bit obsessed with the pre- conceptions of how the spaces for art function, such as the periodical tabula rasa, the complete cleaning up of the space before each new show, which relates to the notions of white-ness and neutrality, which are not true! The physically claimed neutrality is a way to undermine the socio-economico-political frames and infrastructure of how art institutes function. So this action of condensing each exhibition and keeping them in the space, with samples from the original works, photographic documentation of installations, and existing elements or furniture to be re-shaped and re-composed within the same space, but for longer than usual durations and in a periodically growing sense, was a way to intervene in and reconfigure such pre-conceptions. It was also a challenge to the ‘very short-term memory’ not only in art, but in life and politics, in a sense how the city or the country does not tend to accumulate knowledge of its recent past, and how it tries hard not to relate or learn from its recent past. In the end the whole project involved many artists’ blessings, and agreement, as the original pieces were to be re- configured. Not everybody agreed to this, I guess 2 out of 18 artists disagreed, so I ended up showing only photos of their work, taken by other people. However these were balanced with the more inventive contributions, such as Leyla Gediz’s painting. The painting she had shown in the first exhibition of the series belonged to a collection who did not want to take the risk of showing the piece within my constellation. After discussing this situation, Leyla painted a detail of the original round canvas, in 1/1 scale again on a smaller round canvas, which introduced further thoughts of originality, reproduction, and art historical references via the painting being a ‘detail view’ to the first painting. This was an expansion to the original intentions, and really made the installation ‘grow’ and also allowed me to act more freely in the second round of condensation, of making the “Normalization” piece.

Normalization Parts 1 and 2, 2005. Platform Garanti, İstanbul (Photo Oğuzhan Genç)

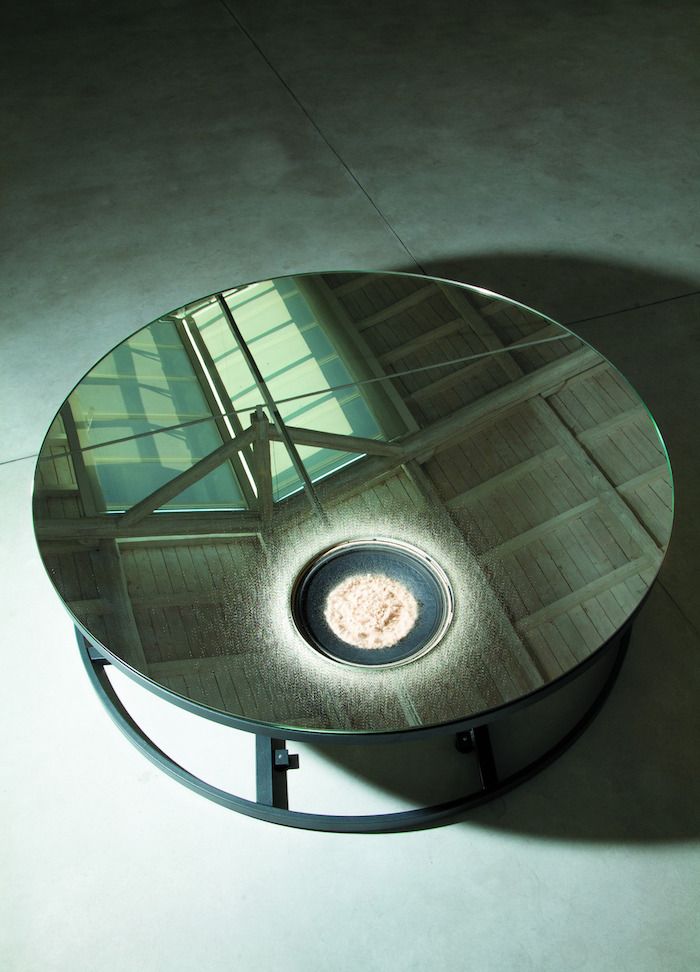

N: The work you proposed for the exhibition “New Ends Old Beginnings” that I curated in 2008 for the Bluecoat gallery in Liverpool was a very different kind of piece. This time the curatorial request was that you respond to your experience of having spent time in Dubai. Was this an unusual experience for you given that so many of your art installations deal with the space of the gallery and the cross-referencing of your work in relation to the other works being exhibited? Perhaps you can describe “Deposit (Spring Deficit: After Dubai, After Hammons, and after the politics of white noise)”, 2008 and how it came about to be a more formal sculptural embodiment?

C: I think that cross-referencing still exists in the piece, but I can also say it was my take on making a self-contained work, producing an object/system, and taking responsibility of its existence, in the world of singularities. That cross-referencing eventually exists as the mirror surface captures its surrounding and those who are looking at the piece. But perhaps I should first tell a bit of the ideas that made it. “Deposit (Spring Deficit: After Hammons, After Dubai, and after the politics of white noise)” is a sculpture, which operates mechanically as a fountain, a fountain that mobilizes sand instead of water, a sand fountain. The sculpture works through the range of potentials a fountain holds. From historically being the key representation of wealth and power, to its religious connotations, to the idea of the ‘spring’; from its uses as public service, charity, to symbolic prestige, to its function as acoustic blockage in meetings on diplomacy; from its importance in Baroque to its unavoidable resonance in 20th century art. I titled the piece before the global crisis emerged, but I see it resonating well with the conditions of today. An aspect related to Dubai is its reflection of Western Discourses; it is a sort of mirror- world where certain things reflect obliquely, or are simply reversed; all the while what constitutes both sides remains as a set of conditions that are rooted in simple capitalism as much as its advanced corporate development. The fountain that remains a fountain but strives to function with sand instead of water is an attempt to pin down that moment of mirroring, not only to illustrate but to commentate via a singular sculptural object (a totality – that circulates grains of sand) instead of other representational or documentational tools and narratives.

Deposit (Spring Deficit: After Hammons, After Dubai, and after the politics of white noise)

Installation view from Between Form and Movement, Galleria Enrico Astuni, Bologna, 2012

Installation view from Between Form and Movement, Galleria Enrico Astuni, Bologna, 2012

The process of making the piece was also interesting. After your invitation/commission and after deciding on the main principles and title, for a long time I discussed with Paul Bartlett, a friend and robotics wizard, about possible ways of making the fountain fully function: as a closed circulation system that works with sand. We looked at mechanical devices used for grains or sanitary powders, I also started looking into what else was available, but all the time the piece was growing more complex and much larger than necessary. It was a focused brain-storm sketching session with Aslı Kalınoğlu, during a train-ride, that first made me realise we could simplify the piece by chopping out certain mechanisms, forms and all that was unnecessary, until we came to the point that the movement of sand was not necessarily through circulation (which was Hammons’ way), instead it could be achieved through sound - and we had already considered sound as integral to the piece. So, sand, sound, mirror, and pond or pool came together in the final form as Deposit.

N: I am intrigued to learn more about another recent installation that you have created for the exhibition “There is no Audience” curated by Adnan Yildiz. Although I did not see the exhibition, from the documentation it felt very much that your structures created a pivot for the other works in the show to gather around. How do you see the relationship between the other works in this exhibition and your intervention in terms of the way it changes the environment, via its semi-functional gesture, for all the participants? Was your response a comment on the ironic proposal of the title?

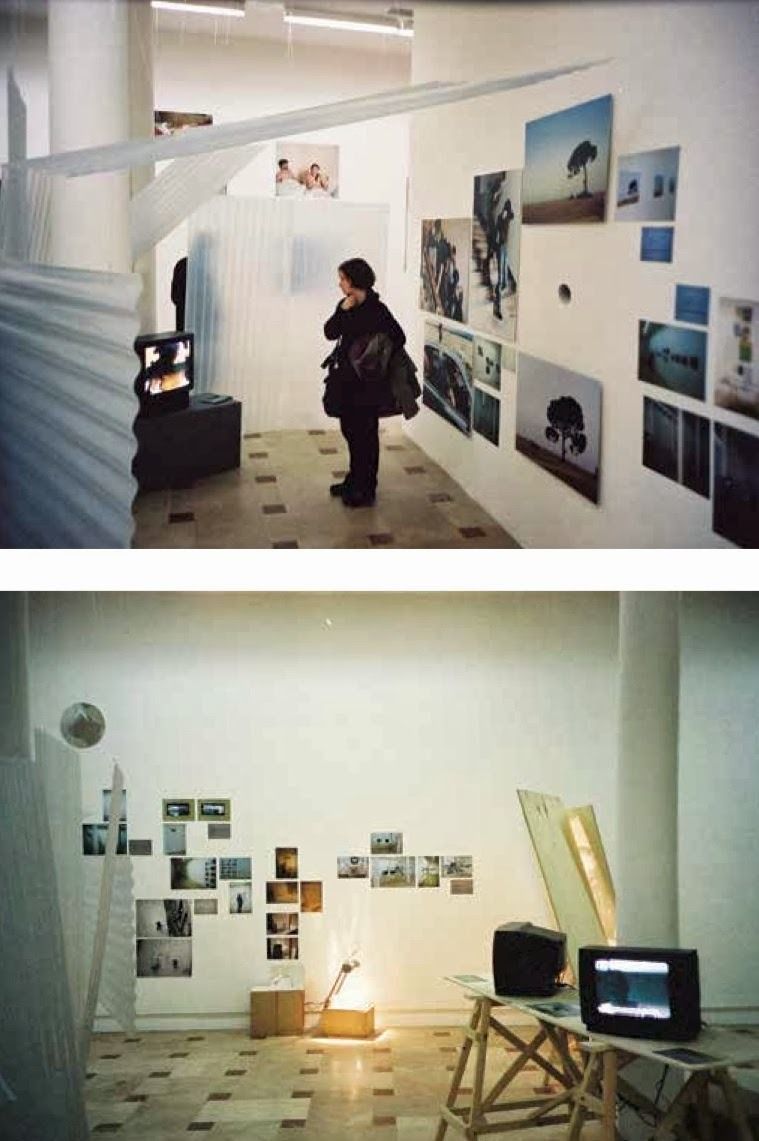

C: “CloudCrowdCloud” (2009) was the piece I developed for that show at Montehermoso. It follows a body of work which I broadly call “setting a setting”. Basically looking into the exhibition space, and the art institute, via their promise of public-ness, or rather asking whether the art context can still offer at least a simulation of a public space. And to do this the piece reproduces very fundamental architectural elements, becomes something between a backdrop, sculpture, an architectural setting, open for use or viewing, but also employs an additional narrative, which brings the piece from mere furniture to a discussion. Here, this narrative is supported by a footnote, a series of posters pasted all over the back surface of the structure, telling about a scene from the film “3 Days of the Condor” which suddenly surfaces questions about where we stand and how the work can be seen. The addition of a photo that shows a pigeon descending stairs in the town-center further complicates things. The whole setting locates at a very central spot in this corridor-like space -there is also the curator’s contribution to an extent here, especially in terms of other artists’ works and how “CloudCrowdCloud” locates amongst them. The piece forms further corridors and thereby multiplies a small space, into an experience of complexity. This was something I previously tried in my solo-show at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien (“Setting a Setting / Forecasting a Broken Past”), where the setting was formed to bring together very different works of mine, by placing these large steps, like a mini- auditorium, which created sub-spaces and supra-spaces in a very small room. I guess these works all try to construct certain complex systems, to be inhabited and used in some ways, determined or not, and also to let go of their possible interpretations through use. “A Damaged Plane” which played the central role in my solo exhibition at Spike Island (“Ey Ahali! / Setting a Setting / Letting a Setting Go”) further embraces this reconfiguration, through its open and invited uses by, amongst others, musicians and sound artists, where each performer had interpreted the setting, while having to reconfigure their own practice and their own habits of performance, as these settings are always slightly dysfunctional.

Setting Nummer Zehn from Setting a Setting / Forecasting a Broken Past. 2008

Installation view from Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. Photo: David Brandt

Installation view from Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. Photo: David Brandt

N: The previous question leads into a larger and ongoing conversation about your position as an architect/artist and how you relate/explore/distinguish your roles within each discipline. The 4th Architecture Biennale in Rotterdam, must have presented a new direction in that you as the co-curator were inviting others to respond to questions that you have been raising within your independent practice. How do you find balance and remain focused when your own role appears to shift and change so often and how do you manage to keep others engaged and responsive to these ambiguities of authorship?

C: That’s something I haven’t resolved fully, and I am questioning more and more whether I should distinguish my position in terms of these defined disciplines. I am deeply interested in the historical constructions around art, and see my work primarily within that universe. On the other hand I am engaged in thinking about ‘space’ as that vital prosthesis which is manifested always already in how we live, and which can only be seen as a complex construct that involves politics, economics, and the social along with physical presence. And cities as ever-changing, multi-layered systems, like the art context, where I have high hopes and belief in that their ‘ways’ need constant challenge, and their rules and pre-conceptions need to be pushed for further re-configuration if not transgression. There is not necessarily an ultimate, final, best condition, but spaces deserve making and re-making, if we agree that there are still things that one is able to achieve, and that a better way is always a promise.

The exhibition “Refuge: architecture for unbound spaces” which I co-curated with Philipp Misselwitz, initially for the 4th Rotterdam Architecture Biennial, and later for our own expanded version in İstanbul, titled “Open City İstanbul”, was a project that looked into cities mainly in the region of Turkey/Middle East (with their counterparts in Europe or elsewhere). We looked at architectural and urban practices that really challenged the existing modes of practice, while producing work that fundamentally holds a clear position against the power-oriented production of space (be it in neo-liberalism, state oppression, or boundary-maintaining), practices that place themselves in a grid full of conflicts, and still act to find inventive ways of providing-, preventing-, improving-, dismantling- the conditions of “refuge” when and where necessary. It was also a way of valuing this work, providing alternatives to given modes of practice, and also bringing forth severe issues about cities, spaces, and of course people, that are still in need of fundamental rights, spatial justice, and if we may call it so, a civic existence.

PARK: bir ihtimal with works by Nils Norman, Ceren Oykut, Sinek Sekiz, and the Park Collective. 2010

Installation view from Istanbul. Photo: Laleper Aytek

Installation view from Istanbul. Photo: Laleper Aytek

Another project that I have been working on, which is called “PARK: bir ihtimal” in a sense brings together all these discussions about space, authorship, collaboration, the city and public space, for the first time, taking place literally in ‘the open’. This project acts within the immediacy of a public audience, as it is located in a park, in the center of İstanbul. It is a small park, yet it is quite crowded, and forms a complex eco-system almost mimicking the whole city. What is again at stake is a kind of collaboration, initially with the group of contributors I invited, and the public, the audience, the passer-by, but also the people who live and work at the park, both officially and unofficially. The project also clashes very individual practices into a whole, to the point that you don’t necessarily perceive any autonomy within each piece. This has to do with the way these works are held together, but also with the very nature of the park, in which every object, every thing, every body, can become something between a contribution and an intervention, which can then add on to this complex eco-system. I invited Nils Norman, whose ideas on public space, ecological discourse, DIY, and the so-called “creative classes” contribute perfectly to the context; Ceren Oykut with her landscape drawings that depict the urban transformation of İstanbul vividly; the publishers and gardeners collective Sinek Sekiz grow vegetables in our urban orchard; the design studio Future Anecdotes provided the signage which is an integral element in the whole, as well as the publication; and a collective work-force of a small group of young artists and architects who have collaborated with me to develop the pieces and elements that bring the pieces together as well as relating the whole project directly to the park context.

N: To conclude, there is one question I have wanted to ask for a while and especially since we recently composed a piece for DOMUS together along with Asli Kalinoglu that referred back to a couple of works including “Exercises in Sharing: Aping Me Aping You” (2007). Where, when and how did your fascination with pigeons come about?

C: Well, I guess it starts from a certain fear and hatred that I eventually reconciled. But the first piece I can recall, was a small drawing which accompanied a photograph, taken at a train station in Germany, dated 2004. Later on, “Exercises in Sharing” became this wider frame within which I presented a pack of chips (the local delicacy) to an urban fox (the local beast) in Cork; collected a vast amount of images of plants and animals that inhabit cities, including that photograph of a pigeon eating from a plate in a pub in Bristol; and proposed an immaterial monument that would partially shatter the possessiveness of pigeon-breeders in Cairo. But this piece with the bread and the defensive pins was the first in the series of works which for me kept on swinging between polemic and archive; between constellations of images and questions of display; between gestures that relate to the ages old separation of “man” (I don’t say human) and “animal”, to issues of sovereignty, hegemony, and freedom. Yet, to answer on a slightly different note: pigeons are people.

A conversation between Can Altay and November Paynter, 2010.

First published in Pigeons are People, 2010

ISBN 978-3-86895-126-4

- 1.Proje4L at the time of its opening was located in Levent, with its entrance facing the recently burgeoning new financial center of İstanbul and its reverse sitting on the cusp of one of the city's largest poorer residential areas Gültepe.

- 2."Minibar" was a project that looked at the phenomena of young people creating a space for themselves through the act of drinking on the streets of Ankara. Every time the authorities created barriers to halt this activity the group would either make use of the new conditions or re-congregate in a different zone of the city.

- 3.Papermen in Turkey are the informal rubbish collectors that sort and select one type of rubbish to later take for recycling. The most common collectors are those of paper and paper-based materials.