Sriniketan and Beyond — Arts and Design Pedagogy in the Rural Sphere

NATASHA GINWALA

30 Mart 2020

Kala Bhavan Campus, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2017

Photo: Grant Watson

Photo: Grant Watson

*This article was originally published at bauhaus-imaginista.org in March 2019.

In this article Natasha Ginwala examines how certain Bauhaus ideas flowed into Tagore’s pedagogic experiment and rural reconstruction program at Sriniketan (created in 1921–22), as well as the engagement with design Dashrath Patel, the founding secretary of the National Institute of Design (NID) and its leading pedagogue, pursued in the rural sphere.

“All around our ashram is a vast open country, bare up to the line of the horizon except for sparsely growing stunted date palms and prickly shrubs struggling with ant-hills.”

Rabindranath Tagore, “My School,” Personality, Macmillan, 1959

Rabindranath Tagore’s growing awareness of structural inequalities in the rural terrain began during the long epoch of colonial modernity, when in 1890, aged twenty-nine, his father put him in charge of the family’s estates in East Bengal. As part of the landed gentry and Bengali elite, the young poet-philosopher’s imagination was at first captured by the countryside’s serene pace. But gradually he became aware of the impoverishment and systemic oppression permeating the everyday life of the peasantry and indigenous minorities in the region. While questioning his ancestral role as a Zamindar, or hereditary landowner, Tagore began to formulate methods for socio-economic transformation in small steps, initiating first a learning center and village library.1

Conceived as an open-form community following a democratic ethos, Santiniketan (the name for an area originally leased by Tagore’s father in 1883, where Tagore himself founded an Ashram in 1901) proposed a universalizing frame for collective learning that, on the one hand, countered the prevailing imperial academic model and, on the other, the traditions that until then had structured the hierarchy within arts pedagogy and creative labor. The communal spirit and ideals of Swadeshi (self-rule) circulating through the freedom movement led to the formulation of powerful strategies for transforming how the rural economy and handicraft production were organized. As a parallel example, we might consider a figure such as the Sri Lankan Tamil philosopher and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, who denounced how the “creative power of the craftsperson” was being actively destroyed by European mercantilism and commercialization of artisanal labor, proclaiming at a public lecture during the Fifth Annual Industrial Conference in 19102 that “industry without art is brutality.” In the same year, Coomaraswamy published the essay, “Art and Swadeshi,” where he positioned aesthetic theory and the economy of the “hand-made” from a South Asian perspective as a way of building solidarity and resistance against Western commercialism, unfair labor conditions (“transferred from Manchester to India”) and industrial trade relations.3

Surrounded by this climate of anticolonial sentiment yet ensconced in the refuge of the Birbhum landscape, Tagore and his compatriots efforts to develop an ethics of self-reliance was not only practiced within the artistic milieu at Kala Bhavana, the art school Tagore founded alongside Visva Bharati University, but more broadly through agricultural experiments in cooperative farming, water management, soil studies and the ecologically grounded seasonal festivals initiated on the rural campus. 4

I wish to examine here how certain Bauhaus ideas flowed into Tagore’s pedagogic experiment and rural reconstruction program at Sriniketan (created in 1921–22), as well as the engagement with design Dashrath Patel, the founding secretary of the National Institute of Design (NID) and its leading pedagogue, pursued in the rural sphere.

The basis of Sriniketan was already established in 1921 when Rabindranath Tagore purchased land for an experimental farm in the village of Surul, three kilometers west of the Santiniketan campus. The English agronomist Leonard Knight Elmhirst began leading the project soon after arriving in November 1921 (hired as Tagore’s secretary), establishing its program based on Tagore’s “Cooperative Principle” of self-reliance through interdependence. Rural development through handicrafts such as weaving, leather, lacquer work and pottery—alongside agronomic training in both traditional rural and modern techniques—were key facets of Sriniketan’s radical education system and research laboratory, which was grounded in the principles of cooperative self-reliance. During his inaugural address for an exhibition of Sriniketan handicrafts in Kolkata, Tagore stated:

“To some of them I pointed out that the drama of national self-expression could not be real if rural India were banished to the outer darkness behind the stage …

… I had started rural service with scanty means and a few companions. My agony did not merely show itself in my poems, it dragged the poet himself to the arduous field of work. What power could an indignant worker possess save in his vision of the truth? …”5

At Sriniketan, the village was envisioned as a core unit where Tagore’s concept of “the world in a nest” would be activated through principles of social renewal, plotted by reciprocal exchange through arts and crafts production, as well as pedagogic and agricultural experimentation. In the early 1920s, the existing communal stakeholder structure included Hindu, Muslim and Santali peasants, alongside students who came together for specific workshops on integrative study—the grounding of academic learning in nature and community life. In Elmhirst’s book, Poet and Plowman, developed out of his diary entries and encounters with Tagore, he wrote:

“My determination to stick to Surul and the job in hand only served to whet his appetite for more regular news of the latest developments. As the months went by I found him ever more eager to come and visit the farm or to find time to discuss the new puzzles as they arose. Politics and political discussions were everywhere in the air, Tagore was being accused, not by Gandhi, but in the Press and by the politicians-in-a-hurry, of being out of touch with the basic mood of India, of being too much of a poet and of a detached educator, of having his head in the international clouds and of not being a thorough-going non-cooperator. His senior students and many of his staff at the Ashram were unable to make out just where I stood either in relation to India’s national aspirations or to Gandhi’s developing program of refusal to cooperate with an Imperial Government. Yet I was obviously working with and under Tagore’s direction, was plainly sympathetic with Indian national aspirations, and was already becoming increasingly conversant with the problems of the local villages and of their people’s needs.”6

During a conversation in 2013 at the home of Noni Gopal Ghosh, an early student who later became one of the school’s senior pedagogue, he highlighted the significance of Sriniketan’s early activities as intrinsic to the daily routine of students from year to year. Thousands were trained in a wide range of techniques through special workshops led by local and international experts, including practical guidance on how handicraft production could potentially gain a more significant domestic market share than finished imported goods. However, this legacy was gradually eroded, with greater attention given to the established departments at Kala Bhavana, which did note use a traditional curriculum in the early years, organized instead around an intergenerational model of artistic pedagogy, with classes structured based on mentorship. These were frequented by an international group of cultural protagonists—including linguists, art historians, weavers, dancers, etc.—who encountered Santiniketan’s educational philosophy in situ.

Starting with the famous “Bauhaus Manifestos and Program” of 1919, Walter Gropius made the concept of a “synthetic artist” a central tenet of the holistic learning approach within Bauhaus workshops. A corollary notion we might consider is that of the “complete artist,” put forward by the renowned Indian artist K. G. Subramanyan, who studied at Kala Bhavana during the 1940s. As an artist, pedagogue and cultural critic who experimented across every possible medium—including weaving, toy-making, glass painting theatre production, mural design and book illustration—Subramanyan developed a complex visual experience within his work, sketched directly from firsthand experience as well as the mythological world, interweaving a variety of folk idioms and indigenous techniques within his paintings. His views on the paramount importance of the rural milieu to cultural pedagogy, as well as the correlation between craft-making and artisanal language to the contemporary visual vocabulary and narrative construction of Indian art—propounded over decades spent as a mentor on the campuses of Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda as well as Santiniketan—remain of seminal importance.

I would like to turn our attention to a figure mentioned earlier in this text, Dashrath Patel. A frequently overlooked facet of his work as a “synthetic artist” was that besides serving as the founder-secretary of the NID, Patel, who over his career practiced painting, ceramics and graphic, industrial and exhibition design, also served as the NID’s director of education from the early 1960s until 1980. During this period, particularly in the 1960s and early ’70s, he ushered through the school an array of innovative thinkers, including Louis Kahn, Frei Otto, John Cage and Buckminster Fuller. Patel’s diverse artistic training began in Madras under the tutelage of Debi Prasad Roy Choudhury and continued in Paris, where he attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts from 1953–55, after which he worked at the ceramic workshop of Otto Eckert in Prague between 1959 and 1960. This range of medial interests alone ensured that he would elude categorization as a pedagogue and visual thinker. 7 Moreover, it was his commitment to design as a social engine, along with his radical search for innovative tools of communication, which led to his continual improvisation in the use of forms, materials and approaches.

There are numerous iconic photographs taken by Patel chronicling the visual syntax of the street economy across India, journeys to the Kumbh Mela and Varanasi, and aerial views of vibrant dyed textiles drying in the sun along the Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad (1961), the latter made after meeting Henri Cartier-Bresson (the river is now leaner and choked by an embankment and dense road infrastructure). Of particular relevance here is Patel’s photographic documentation of Mithila painting and artists from Madhubani, made for the Calico Museum collection between 1958 and 1981. This visual record captures the generational transformation of Mithila painting, an art form deeply enmeshed in the region’s way of life, set within a flood-prone terrain. In association with NID’s approach to “craft documentation”—which from a critical position may also be viewed as assuming an at times extractive mode in the designer-artisan equation—Patel’s was not simply an archival impulse capturing the artist-craftsperson in isolation but, rather, an attempt to survey the socio-economic struggles and spiritual-cosmological system tying the community to the Madhubani landscape.

Another significant contribution made by Patel was the Rural Design School, established at Sewapuri, near Varanasi, between 1984 and 1991.8 After resigning from the NID in 1980, he introduced a range of facilities and products to the Sewapuri studios, designed to accommodate local low-tech conditions while still producing high quality goods, ranging from ceramics to leather ware, woodwork, stone and naturally dyed textiles. Combining artisanal techniques with a contemporary design sensibility, Patel’s leadership as an educator shone through in this initiative. He remained equally concerned with the economic viability of the school’s production output, keeping an eye on sustainability, output quality and the market chains that connected rural producers to the urban centers where their goods were sold. He helped to establish an intergenerational workshop teaching format to ensure that processes of mentorship were established as a communitarian process within Saghan Kshetra Vikas Samiti, a Gandhian integrated rural development project. After almost eight successful years, in which the school was able to prove it could succeed as an alternative development model, the experiment began to suffer reverses due to internal politics and caste tensions within the village and was finally abandoned, coinciding with the closure of the SKVS itself.9

The cultural critic Sadanand Menon, a close associate of Patel’s, has noted: “In later years, Dashrath also developed a significant critique of ‘styling’ over ‘design.’ He used to say that while, generally, the emphasis in the design process has to be on public ‘need,’ its economic capacity, effective deliverance, infrastructural sustenance and flexible production methods, designers had failed to comprehend this.”10 Similarly, Singanapalli Balaram and other NID faculty members such as M.P. Ranjan also attempted to address the failures of industrial design at the level of economic welfare and equitable development through experimental models meant to provide intelligent and efficient design products that could potentially address the gap between India’s prevalent cottage industry models and industrial mass-production. (It was not necessarily the case that Balaram, Patel and Ranjan were fully in concord with each other’s methodology regarding the question of handicraft vis-a-vis industrial production, but each was able to make a unique contribution to the NID at different phases of the school’s history, with varying degrees of success in realizing their production models internally and externally.) In The Barefoot Designer: Design as Service to Rural People (1998), Balaram notes, “The second and even more serious concern, which should be the concern of every conscientious designer, is urbanisation of design. Design has remained essentially an urban activity everywhere. The attempts of urban Indian designers to design village products such as the bullock-cart or the sickle have been largely unsuccessful. The reason simply is that they were alienated solutions within the same land.”

In introductory remarks to The Robbery of the Soil, Rabindranath Tagore presented a prognostic critique of private property and the bourgeois class. While given his social background this assessment can also be construed as self-analysis, the text also conflates Tagore’s vision for Sriniketan with his larger political commitment as one of the leading intellectuals of the intermingled histories that make up Pan-Asian modernity.

“Civilisation was supported by strong pillars of property, and wealth gave opportunity to the fortunate for self-sacrifice. But, with the rise of the standard of living, property changes its aspect. It shuts the gate of hospitality which is the best means of social communication. Its owners display their wealth in an extravagance which is self-centered. This creates envy and irreconcilable class division. In other words property becomes anti-social.”11

Rabindranath Tagore visited the Netherlands in 1920. Paying a visit to the colonial institute in Amsterdam, he stood amidst its vast cultural holdings and was moved at the sight of the temple ruins of Java and ceremonial artifacts of the archipelago, held there as “museal” objects. Tagore had never before directly encountered these ornate, sacred architectural forms from East Asia, and he lamented how they had become alienated from the civilizational grounds where they were first created and held a particular social function. This visit convinced him that he should not delay further a trip to the archipelagos of South East Asia. He began establishing contacts in the region in the hope of arranging hosts and intermediaries for the different legs of his proposed journey. He eventually embarked on this seminal voyage in 1927, which included a comprehensive tour and lectures throughout Thailand, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, Penang, Sumatra, Java and Bali. It remains an emblematic chapter in his effort to build an integrated Pan-Asian approach to learning on the rural campus.

Tagore’s traveling companions included the artist, architect and Kala Bhavan faculty member Surendranath Kar, who made extensive illustration throughout the trip, plotting ancient monuments and making renderings of examples of handicraft techniques, folkloric practices and detailed studies of architectural elements. He also studied Javanese Batik so it could be taught at Santiniketan. The artist Pratima Devi, Tagore’s daughter-in-law, keenly observed the practices of Balinese dance-drama and costumes as sketched by Kar, introducing these to the Tagorian dance-drama lexicon upon their return. The linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji documented the tour in writing, playing a key role during meetings with literary figures and archaeologists. It was in 1928, after the group returned from their tour, that the festivals within Visva-Bharati began to take on a broader Pan-Asian sensibility, furthering their secular, easterly oriented dimension.In locating Tagore’s approach to Asian Universalism, the historian Sugata Bose reflects on how:

“an interplay of competing and multiple universalisms – universalism with a difference, the sanctimonious hypocrisy of the colonizer stood in opposition to the wretched abjection of the colonized. Players in cosmopolitan thought zones delivering shape to a global future. Their cosmopolitanism flowed not from the stratosphere of abstract reason, but from the fertile ground of local knowledge and learning in the vernacular.”12

During his Pan-Asian travels, Tagore also addressed the fragility of the itinerant body—how, amidst competing universalisms, the pathways of knowledge eventually needed to be understood not through the unmoored laboring body, with its alert mind that is never quite situated in one home, but, rather, through an expanded, whirling realm of cosmopolitan contact. He writes: “I know people (I need not name them) who, if the opportunity but came, are ready to play the tourist to perfection all their lives, but whom fate has tied down to their household duties in a particular part of Cornwallis Street. And here am I, who finds comfort in letting my mind range through the skies only when my body is at rest in its corner, doomed to flit from port to port. So I am off, not home-wards but Siam-wards.”13

- - -

The research and conceptualization of this article is related to the exhibition chapter Dakghar: Notes Toward Isolation and Recognition by Landings (with Vivian Ziherl) in Tagore’s Post Office curated by Grant Watson at neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK), Berlin (29 March – 1 June 2014) and was developed further for Bauhaus Imaginista symposiums in Tokyo (August 2018) and New Delhi (December 2018).

In this article Natasha Ginwala examines how certain Bauhaus ideas flowed into Tagore’s pedagogic experiment and rural reconstruction program at Sriniketan (created in 1921–22), as well as the engagement with design Dashrath Patel, the founding secretary of the National Institute of Design (NID) and its leading pedagogue, pursued in the rural sphere.

“All around our ashram is a vast open country, bare up to the line of the horizon except for sparsely growing stunted date palms and prickly shrubs struggling with ant-hills.”

Rabindranath Tagore, “My School,” Personality, Macmillan, 1959

Rabindranath Tagore’s growing awareness of structural inequalities in the rural terrain began during the long epoch of colonial modernity, when in 1890, aged twenty-nine, his father put him in charge of the family’s estates in East Bengal. As part of the landed gentry and Bengali elite, the young poet-philosopher’s imagination was at first captured by the countryside’s serene pace. But gradually he became aware of the impoverishment and systemic oppression permeating the everyday life of the peasantry and indigenous minorities in the region. While questioning his ancestral role as a Zamindar, or hereditary landowner, Tagore began to formulate methods for socio-economic transformation in small steps, initiating first a learning center and village library.1

Conceived as an open-form community following a democratic ethos, Santiniketan (the name for an area originally leased by Tagore’s father in 1883, where Tagore himself founded an Ashram in 1901) proposed a universalizing frame for collective learning that, on the one hand, countered the prevailing imperial academic model and, on the other, the traditions that until then had structured the hierarchy within arts pedagogy and creative labor. The communal spirit and ideals of Swadeshi (self-rule) circulating through the freedom movement led to the formulation of powerful strategies for transforming how the rural economy and handicraft production were organized. As a parallel example, we might consider a figure such as the Sri Lankan Tamil philosopher and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, who denounced how the “creative power of the craftsperson” was being actively destroyed by European mercantilism and commercialization of artisanal labor, proclaiming at a public lecture during the Fifth Annual Industrial Conference in 19102 that “industry without art is brutality.” In the same year, Coomaraswamy published the essay, “Art and Swadeshi,” where he positioned aesthetic theory and the economy of the “hand-made” from a South Asian perspective as a way of building solidarity and resistance against Western commercialism, unfair labor conditions (“transferred from Manchester to India”) and industrial trade relations.3

Surrounded by this climate of anticolonial sentiment yet ensconced in the refuge of the Birbhum landscape, Tagore and his compatriots efforts to develop an ethics of self-reliance was not only practiced within the artistic milieu at Kala Bhavana, the art school Tagore founded alongside Visva Bharati University, but more broadly through agricultural experiments in cooperative farming, water management, soil studies and the ecologically grounded seasonal festivals initiated on the rural campus. 4

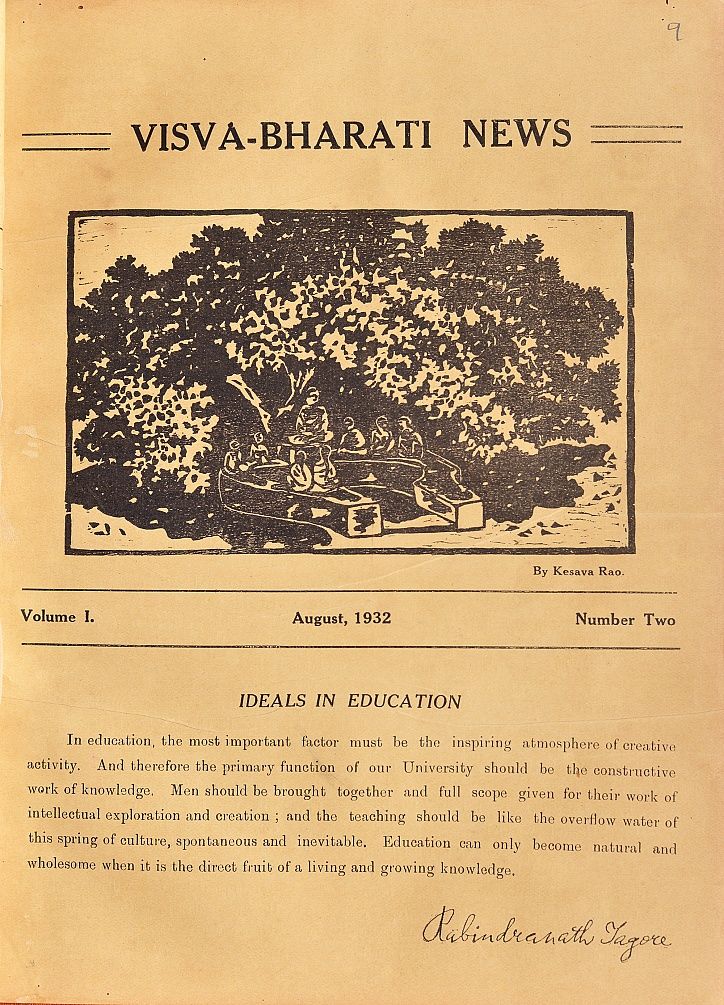

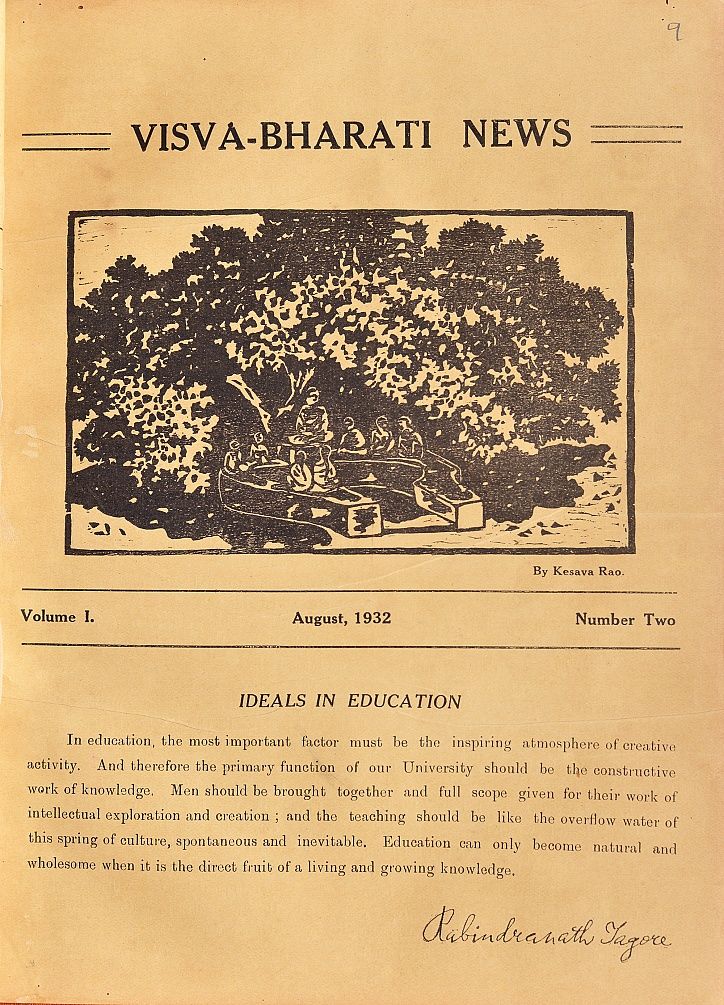

Visva-Bharati News, Vol. 1, No. 2, August 1932, n.p.

Museum Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

Museum Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan

I wish to examine here how certain Bauhaus ideas flowed into Tagore’s pedagogic experiment and rural reconstruction program at Sriniketan (created in 1921–22), as well as the engagement with design Dashrath Patel, the founding secretary of the National Institute of Design (NID) and its leading pedagogue, pursued in the rural sphere.

The basis of Sriniketan was already established in 1921 when Rabindranath Tagore purchased land for an experimental farm in the village of Surul, three kilometers west of the Santiniketan campus. The English agronomist Leonard Knight Elmhirst began leading the project soon after arriving in November 1921 (hired as Tagore’s secretary), establishing its program based on Tagore’s “Cooperative Principle” of self-reliance through interdependence. Rural development through handicrafts such as weaving, leather, lacquer work and pottery—alongside agronomic training in both traditional rural and modern techniques—were key facets of Sriniketan’s radical education system and research laboratory, which was grounded in the principles of cooperative self-reliance. During his inaugural address for an exhibition of Sriniketan handicrafts in Kolkata, Tagore stated:

“To some of them I pointed out that the drama of national self-expression could not be real if rural India were banished to the outer darkness behind the stage …

… I had started rural service with scanty means and a few companions. My agony did not merely show itself in my poems, it dragged the poet himself to the arduous field of work. What power could an indignant worker possess save in his vision of the truth? …”5

At Sriniketan, the village was envisioned as a core unit where Tagore’s concept of “the world in a nest” would be activated through principles of social renewal, plotted by reciprocal exchange through arts and crafts production, as well as pedagogic and agricultural experimentation. In the early 1920s, the existing communal stakeholder structure included Hindu, Muslim and Santali peasants, alongside students who came together for specific workshops on integrative study—the grounding of academic learning in nature and community life. In Elmhirst’s book, Poet and Plowman, developed out of his diary entries and encounters with Tagore, he wrote:

“My determination to stick to Surul and the job in hand only served to whet his appetite for more regular news of the latest developments. As the months went by I found him ever more eager to come and visit the farm or to find time to discuss the new puzzles as they arose. Politics and political discussions were everywhere in the air, Tagore was being accused, not by Gandhi, but in the Press and by the politicians-in-a-hurry, of being out of touch with the basic mood of India, of being too much of a poet and of a detached educator, of having his head in the international clouds and of not being a thorough-going non-cooperator. His senior students and many of his staff at the Ashram were unable to make out just where I stood either in relation to India’s national aspirations or to Gandhi’s developing program of refusal to cooperate with an Imperial Government. Yet I was obviously working with and under Tagore’s direction, was plainly sympathetic with Indian national aspirations, and was already becoming increasingly conversant with the problems of the local villages and of their people’s needs.”6

During a conversation in 2013 at the home of Noni Gopal Ghosh, an early student who later became one of the school’s senior pedagogue, he highlighted the significance of Sriniketan’s early activities as intrinsic to the daily routine of students from year to year. Thousands were trained in a wide range of techniques through special workshops led by local and international experts, including practical guidance on how handicraft production could potentially gain a more significant domestic market share than finished imported goods. However, this legacy was gradually eroded, with greater attention given to the established departments at Kala Bhavana, which did note use a traditional curriculum in the early years, organized instead around an intergenerational model of artistic pedagogy, with classes structured based on mentorship. These were frequented by an international group of cultural protagonists—including linguists, art historians, weavers, dancers, etc.—who encountered Santiniketan’s educational philosophy in situ.

Starting with the famous “Bauhaus Manifestos and Program” of 1919, Walter Gropius made the concept of a “synthetic artist” a central tenet of the holistic learning approach within Bauhaus workshops. A corollary notion we might consider is that of the “complete artist,” put forward by the renowned Indian artist K. G. Subramanyan, who studied at Kala Bhavana during the 1940s. As an artist, pedagogue and cultural critic who experimented across every possible medium—including weaving, toy-making, glass painting theatre production, mural design and book illustration—Subramanyan developed a complex visual experience within his work, sketched directly from firsthand experience as well as the mythological world, interweaving a variety of folk idioms and indigenous techniques within his paintings. His views on the paramount importance of the rural milieu to cultural pedagogy, as well as the correlation between craft-making and artisanal language to the contemporary visual vocabulary and narrative construction of Indian art—propounded over decades spent as a mentor on the campuses of Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda as well as Santiniketan—remain of seminal importance.

I would like to turn our attention to a figure mentioned earlier in this text, Dashrath Patel. A frequently overlooked facet of his work as a “synthetic artist” was that besides serving as the founder-secretary of the NID, Patel, who over his career practiced painting, ceramics and graphic, industrial and exhibition design, also served as the NID’s director of education from the early 1960s until 1980. During this period, particularly in the 1960s and early ’70s, he ushered through the school an array of innovative thinkers, including Louis Kahn, Frei Otto, John Cage and Buckminster Fuller. Patel’s diverse artistic training began in Madras under the tutelage of Debi Prasad Roy Choudhury and continued in Paris, where he attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts from 1953–55, after which he worked at the ceramic workshop of Otto Eckert in Prague between 1959 and 1960. This range of medial interests alone ensured that he would elude categorization as a pedagogue and visual thinker. 7 Moreover, it was his commitment to design as a social engine, along with his radical search for innovative tools of communication, which led to his continual improvisation in the use of forms, materials and approaches.

There are numerous iconic photographs taken by Patel chronicling the visual syntax of the street economy across India, journeys to the Kumbh Mela and Varanasi, and aerial views of vibrant dyed textiles drying in the sun along the Sabarmati River in Ahmedabad (1961), the latter made after meeting Henri Cartier-Bresson (the river is now leaner and choked by an embankment and dense road infrastructure). Of particular relevance here is Patel’s photographic documentation of Mithila painting and artists from Madhubani, made for the Calico Museum collection between 1958 and 1981. This visual record captures the generational transformation of Mithila painting, an art form deeply enmeshed in the region’s way of life, set within a flood-prone terrain. In association with NID’s approach to “craft documentation”—which from a critical position may also be viewed as assuming an at times extractive mode in the designer-artisan equation—Patel’s was not simply an archival impulse capturing the artist-craftsperson in isolation but, rather, an attempt to survey the socio-economic struggles and spiritual-cosmological system tying the community to the Madhubani landscape.

Another significant contribution made by Patel was the Rural Design School, established at Sewapuri, near Varanasi, between 1984 and 1991.8 After resigning from the NID in 1980, he introduced a range of facilities and products to the Sewapuri studios, designed to accommodate local low-tech conditions while still producing high quality goods, ranging from ceramics to leather ware, woodwork, stone and naturally dyed textiles. Combining artisanal techniques with a contemporary design sensibility, Patel’s leadership as an educator shone through in this initiative. He remained equally concerned with the economic viability of the school’s production output, keeping an eye on sustainability, output quality and the market chains that connected rural producers to the urban centers where their goods were sold. He helped to establish an intergenerational workshop teaching format to ensure that processes of mentorship were established as a communitarian process within Saghan Kshetra Vikas Samiti, a Gandhian integrated rural development project. After almost eight successful years, in which the school was able to prove it could succeed as an alternative development model, the experiment began to suffer reverses due to internal politics and caste tensions within the village and was finally abandoned, coinciding with the closure of the SKVS itself.9

The cultural critic Sadanand Menon, a close associate of Patel’s, has noted: “In later years, Dashrath also developed a significant critique of ‘styling’ over ‘design.’ He used to say that while, generally, the emphasis in the design process has to be on public ‘need,’ its economic capacity, effective deliverance, infrastructural sustenance and flexible production methods, designers had failed to comprehend this.”10 Similarly, Singanapalli Balaram and other NID faculty members such as M.P. Ranjan also attempted to address the failures of industrial design at the level of economic welfare and equitable development through experimental models meant to provide intelligent and efficient design products that could potentially address the gap between India’s prevalent cottage industry models and industrial mass-production. (It was not necessarily the case that Balaram, Patel and Ranjan were fully in concord with each other’s methodology regarding the question of handicraft vis-a-vis industrial production, but each was able to make a unique contribution to the NID at different phases of the school’s history, with varying degrees of success in realizing their production models internally and externally.) In The Barefoot Designer: Design as Service to Rural People (1998), Balaram notes, “The second and even more serious concern, which should be the concern of every conscientious designer, is urbanisation of design. Design has remained essentially an urban activity everywhere. The attempts of urban Indian designers to design village products such as the bullock-cart or the sickle have been largely unsuccessful. The reason simply is that they were alienated solutions within the same land.”

In introductory remarks to The Robbery of the Soil, Rabindranath Tagore presented a prognostic critique of private property and the bourgeois class. While given his social background this assessment can also be construed as self-analysis, the text also conflates Tagore’s vision for Sriniketan with his larger political commitment as one of the leading intellectuals of the intermingled histories that make up Pan-Asian modernity.

“Civilisation was supported by strong pillars of property, and wealth gave opportunity to the fortunate for self-sacrifice. But, with the rise of the standard of living, property changes its aspect. It shuts the gate of hospitality which is the best means of social communication. Its owners display their wealth in an extravagance which is self-centered. This creates envy and irreconcilable class division. In other words property becomes anti-social.”11

Rabindranath Tagore visited the Netherlands in 1920. Paying a visit to the colonial institute in Amsterdam, he stood amidst its vast cultural holdings and was moved at the sight of the temple ruins of Java and ceremonial artifacts of the archipelago, held there as “museal” objects. Tagore had never before directly encountered these ornate, sacred architectural forms from East Asia, and he lamented how they had become alienated from the civilizational grounds where they were first created and held a particular social function. This visit convinced him that he should not delay further a trip to the archipelagos of South East Asia. He began establishing contacts in the region in the hope of arranging hosts and intermediaries for the different legs of his proposed journey. He eventually embarked on this seminal voyage in 1927, which included a comprehensive tour and lectures throughout Thailand, Burma, Malaya, Singapore, Penang, Sumatra, Java and Bali. It remains an emblematic chapter in his effort to build an integrated Pan-Asian approach to learning on the rural campus.

Tagore’s traveling companions included the artist, architect and Kala Bhavan faculty member Surendranath Kar, who made extensive illustration throughout the trip, plotting ancient monuments and making renderings of examples of handicraft techniques, folkloric practices and detailed studies of architectural elements. He also studied Javanese Batik so it could be taught at Santiniketan. The artist Pratima Devi, Tagore’s daughter-in-law, keenly observed the practices of Balinese dance-drama and costumes as sketched by Kar, introducing these to the Tagorian dance-drama lexicon upon their return. The linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji documented the tour in writing, playing a key role during meetings with literary figures and archaeologists. It was in 1928, after the group returned from their tour, that the festivals within Visva-Bharati began to take on a broader Pan-Asian sensibility, furthering their secular, easterly oriented dimension.In locating Tagore’s approach to Asian Universalism, the historian Sugata Bose reflects on how:

“an interplay of competing and multiple universalisms – universalism with a difference, the sanctimonious hypocrisy of the colonizer stood in opposition to the wretched abjection of the colonized. Players in cosmopolitan thought zones delivering shape to a global future. Their cosmopolitanism flowed not from the stratosphere of abstract reason, but from the fertile ground of local knowledge and learning in the vernacular.”12

During his Pan-Asian travels, Tagore also addressed the fragility of the itinerant body—how, amidst competing universalisms, the pathways of knowledge eventually needed to be understood not through the unmoored laboring body, with its alert mind that is never quite situated in one home, but, rather, through an expanded, whirling realm of cosmopolitan contact. He writes: “I know people (I need not name them) who, if the opportunity but came, are ready to play the tourist to perfection all their lives, but whom fate has tied down to their household duties in a particular part of Cornwallis Street. And here am I, who finds comfort in letting my mind range through the skies only when my body is at rest in its corner, doomed to flit from port to port. So I am off, not home-wards but Siam-wards.”13

The research and conceptualization of this article is related to the exhibition chapter Dakghar: Notes Toward Isolation and Recognition by Landings (with Vivian Ziherl) in Tagore’s Post Office curated by Grant Watson at neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst (nGbK), Berlin (29 March – 1 June 2014) and was developed further for Bauhaus Imaginista symposiums in Tokyo (August 2018) and New Delhi (December 2018).

- 1.Kathleen M. O' Connell: Rabindranath Tagore: The Poet as Educator, Visva-Bharati, Kolkata 2002, 2011.

- 2.See William W. Quinn: The Only Tradition, SUNY Press, Albany 1997, p. 255.

- 3.Ananda K Coomaraswamy: Art And Swadeshi, Ganesh & Co. Publishers: Madras 1910. archive.org (Accessed 19 July 2019)

- 4.I would like to extend my gratitude to Sanchayan Ghosh for conversations and visits to Santiniketan, especially his thoughts on cultural pedagogy through communal eco-political practices connected to the land.

- 5.Speech sourced in Rabindra Bhavana Archives, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan, date unknown.

- 6.Leonard K. Elmhirst: Poet and Plowman, Visva-Bharati Publishing Department, Santiniketan First published: September 1975. p 16–25.

- 7.See Gita Jayaraj: An Iconic Mainstream Artist Who Stayed Invisible. thewire.in (Accessed: 19 July 2019)

- 8.Sadanand Menon (Ed.): In the Realm of the Visual, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi 1998.

- 9.See Jayaraj: An Iconic Mainstream Artist Who Stayed Invisible.

- 10.Sadanand Menon: "Visual Thinker" (obituary of Dashrath Patel). frontline.thehindu.com (Accessed: 12 August 2019)

- 11.Elmhirst: Poet and Plowman, p. 33–34.

- 12.Sugata Bose: Rabindranath Tagore and Asian Universalism, Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, Singapore.

- 13.Rabindranath Tagore: Letters from Java (1927), "Letter 20," Supriya Roy (ed.), Visva-Bharati 2010.